In 1959, John Cohen went searching for something. Were you to ask him at the time, before he headed south toward Kentucky from New York by way of bus, he might’ve responded that it had to do with a sound. But underneath that sonic exploration lay an interest in weightier connections beyond what he’d heard pour out of his family’s speakers when his mother or his father dropped the needle on a new Frank Sinatra LP. Cohen was looking for a connection.

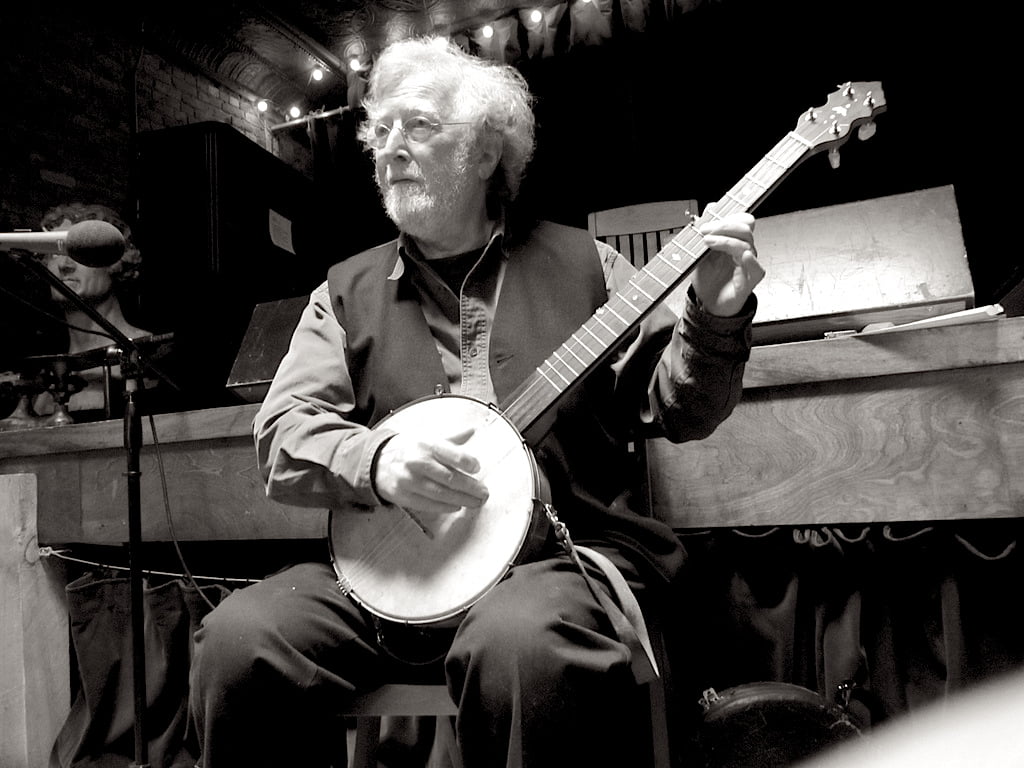

Over the course of his long and varied career, Cohen has been a musician, a filmmaker, a photographer, and more, but at the heart of those titles — and the identities they color — exists a desire to cull the past for its most earnest and forgotten correspondences. As if the banjo playing of Roscoe Holcomb or the traditional songs Cohen performed with his band the New Lost City Ramblers in the 1950s and 1960s, and more recently with the Down Hill Strugglers, contained an integral message to be cared for and passed on. It’s an appreciation for the past that has led some to describe him as a documentarian or a historian or even a preservationist, but any such qualifier only strikes Cohen as being too stiff for the living things they contain.

Cohen will be performing with the Brooklyn-based old-time string band the Down Hill Strugglers at the Brooklyn Folk Festival beginning April 28. He joins a host of traditional and world sounds that have shaped him and continue to inform his listening aesthetic to this day. The search, after all, is never finished.

You’ve mentioned before how you wanted to differentiate yourself from your parents and the standards they listened to at the time — like Frank Sinatra — and, later, the collegiate trend within the folk revival. How did class factor into your taste?

My grandparents were immigrants. My parents were children of immigrants in New York City and, in the process of distancing themselves from their parents’ orthodox Russian Jewish background, they let us kids run wild in American culture. We lived in working class Queens, a place called Sunnyside, but around my 10th birthday, they changed classes and went down to the suburbs and took me with them. And I became middle-class.

By the end of my years in high school, I felt something was wrong and I became an open revolt against that. Music was an important part of my realization of what a cocoon the suburbs were. When I heard Woody Guthrie — this is 1948 I’m talking about — and the Carter Family and Uncle Dave Macon, well, it just opened my horizons. It showed me things about America that I had never even heard of. Here I was listening to Lead Belly when I came home from high school, while everyone else was listening to Frank Sinatra. I was on a very different track, and it’s been that for the next 70 years.

Authenticity is such a loaded word, and yet it seems like you were turned off of the pageantry and production that surrounded popular music at the time. What were you pursuing in this kind of sound?

It completed the picture. The middle class, the Frank Sinatra, the comfortable life, and even the things around rock ‘n’ roll, which are really beautiful and exciting but pretty safe … and then suddenly to see this other side to things. That put the two together and made a much bigger picture. I spent many years making films and photographs in Peru, and it’s even more profound there because the culture is so different. Everything is so different than what we’re raised on here in America. I’m not a universal man, but I have this sense of seeing things from many sides at once. I’m satisfied that I got to that place.

Now we have the Internet and infinite discovery at our fingertips, but you really had to go searching, especially with regards to music.

Eli Smith, a dear friend of mine who presents the Brooklyn Folk Festival, gave me an iPod a couple of years ago loaded with 15,000 tunes, but they’re mostly old blues, old hillbilly music, traditional music, and music from all around the world. I just can’t believe how much joy it gives me, and it’s not exactly “joy” because I put it on shuffle. One moment I’m listening to a Ukrainian orchestra and then, in the next moment, an old bluegrass band. In my mind, I’m constantly asking, “What is it about this music that can make me feel so good about each of them, or what do they have in common?” There’s a certain age to the music, to the singing, a certain vigor that you don’t find in every day life.

A certain connectivity?

Yeah, I mean I could go into ethnomusicology terms, but that’s just a structure around it. It’s a feeling, an intensity. There’s a wonderful writer and musician named Julius Lester and, during the Vietnam War, he went up to North Vietnam and said at midnight they were at the edge of the river waiting for a ferryboat to come and get them across. A ferryboat was just one man in a little boat with an oar, and [Lester] said that man was singing and it sounded just like Clarence Ashley, who was an Appalachian singer from the 1920s. To hear that, it explains it. The same feeling, the same ache to the voice, the same explanation of a life.

These subjects are universal. You’ve described yourself as an artist not a documentarian, and — as a thought experiment — if you put those two identities on the same spectrum, I wonder if you won’t fall somewhere in the middle, like a preservationist, if that’s not too staunch of a term.

It is. It reminds me of formaldehyde. Walter Evans, a wonderful photographer, he used the phrase, “Well, I work in a documentary style,” which means it looks like what people think a documentary is, but that doesn’t mean that it really is. The other thing that I find all over the place is that the word “interpretation” comes in more. I look objectively. I take a photograph: It’s a lens, it’s a film, it’s a fact. But by the time I finish with it, it’s an interpretation. In a way, it holds true for my music, too. I don’t consider myself to be an original musician. The origins are somewhere else, and I’m constantly interpreting those origins. That’s the way I have to look at it.

Yes, but you’re also interested in sticking to the instrumental and melodic foundation. There’s an inclination to preserve there.

I use that as the tools with which I work, but I admire so much and I’m so moved by some of the inventive old sounds that it’s my attempt to get at that. Of course, I can never be them — I can never be Clarence Ashley — but I can reach for it, as long as I don’t lose sight of the original. And very often when I sing or perform, I’ll refer to the source … and it’s not for historical reasons or anything; it just helps me get through the song.

A seeking instinct led you to Kentucky, and the idea of seeking has shifted in recent decades. Have we lost anything?

With the Internet and a lot of phonograph records, you can get the illusion that you’re with someone else and still be sitting on your sofa. But the real trick is to get up off the sofa and get out the door and go somewhere else. And don’t go as a tourist. Tourism is one of the biggest industries in the whole world right now, but that’s because people are looking for something beyond themselves. They don’t know how to approach it. I mean, I went down looking for banjo recordings.

Door-to-door, no less.

More gas station to gas station. And once the folks start retuning the banjo, it opens up their memories of songs they hadn’t played in years or sounds that they don’t play regularly. It’s like a continual opening up of very special things when you have something that you’re after.

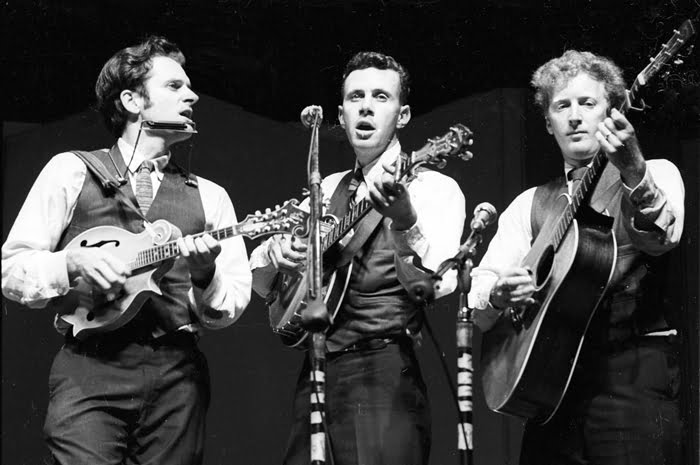

New Lost City Ramblers at Newport Folk Festival

I look at the Internet and obviously someone could “seek” by searching, but you lose that face-to-face connectivity.

Oh yeah, and all the questions like, “Where am I going to eat?” When you go somewhere else, you gotta ask those questions yourself, unless you stay on the main path all the time. One of the things about my approach to music — and it’s not just me alone — is when you hear something that you wanna get at and you try to play it, you’re engaging in a very different way. You have to listen again; you have to listen closely. That’s another form of engagement. I guess it’s about seeking the experience of making music or participating in it rather than just listening to it.

What excites you about the Brooklyn Folk Festival?

It’s a reflection of all the things I’ve been talking about. It’s a great opportunity to see these people in person and hear the music in person, but again, you’re not sitting in your living room with your headphones on. You’re there.

Like you said, opening up the experience.

Yeah, the depth of variety of music … it’s like that iPod. It’s loaded with stuff from all over the place and strong because it’s been curated: They selected one group rather than another. And it goes back in time, as well as being contemporary.

Years ago, in 1961, we formed an organization called the Friends of Old-Time Music and our purpose, for the first time, was to bring traditional performers from the countryside into the city and give them solo concerts. It was the first time we had tried that. Very often, you have a traditional American singer come and be a guest on a Pete Seeger show or a festival or something. Here we were putting on full concerts and that kind of set things in motion in this direction.

Nowadays we’re enjoying the culmination of that exposure.

When my band the New Lost City Ramblers started in 1958, we tried to get at that music: The music that wasn’t being heard, we tried to perform it. We were showing that city kids or urban kids or kids from another tradition could really involve themselves in performing this music, and I’m so proud, after all these years, to see the size of the string bands. There’re festivals and there’re gatherings; it’s all over the place. How many young men and young women study violin and then they change their mind and they play fiddle music? They’re off and running.

Lede photo: John Cohen with Doc Watson and Mississippi John Hurt. All photos courtesy of John Cohen.