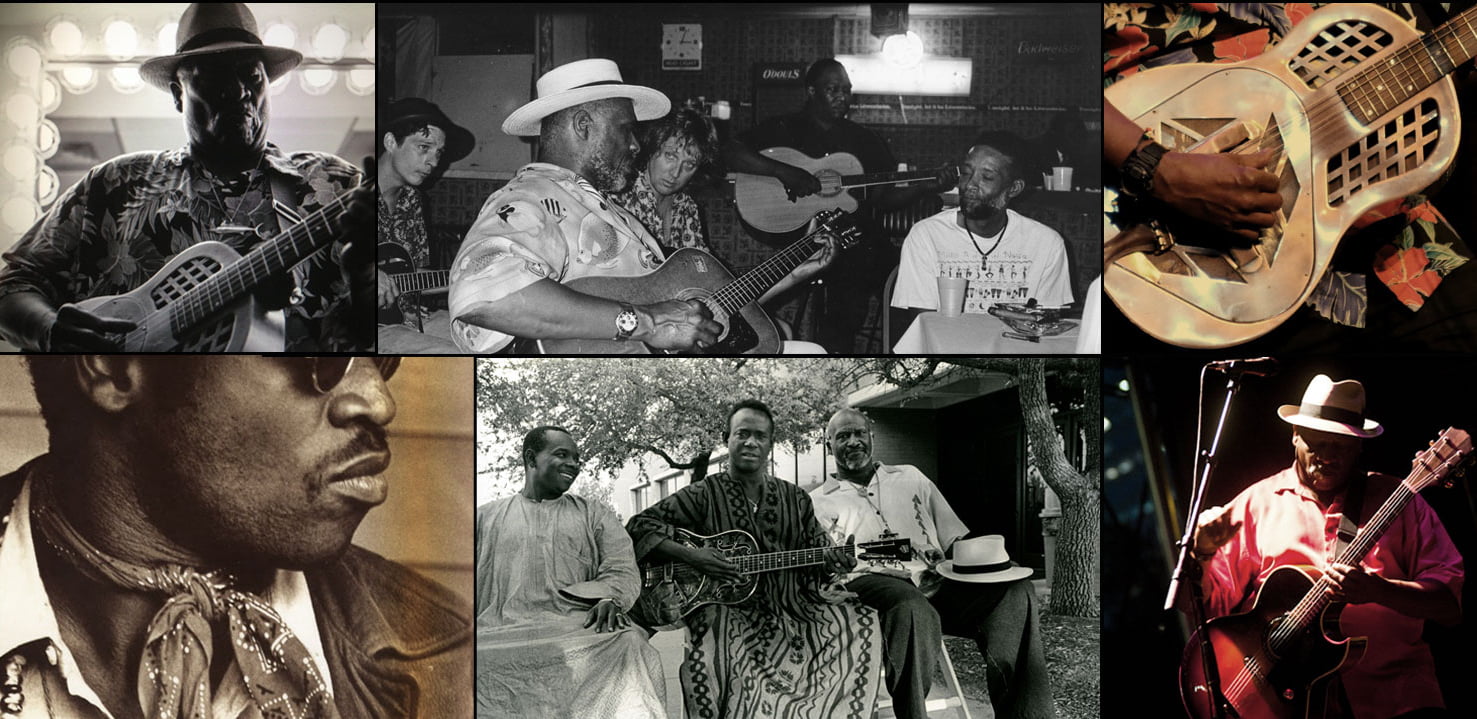

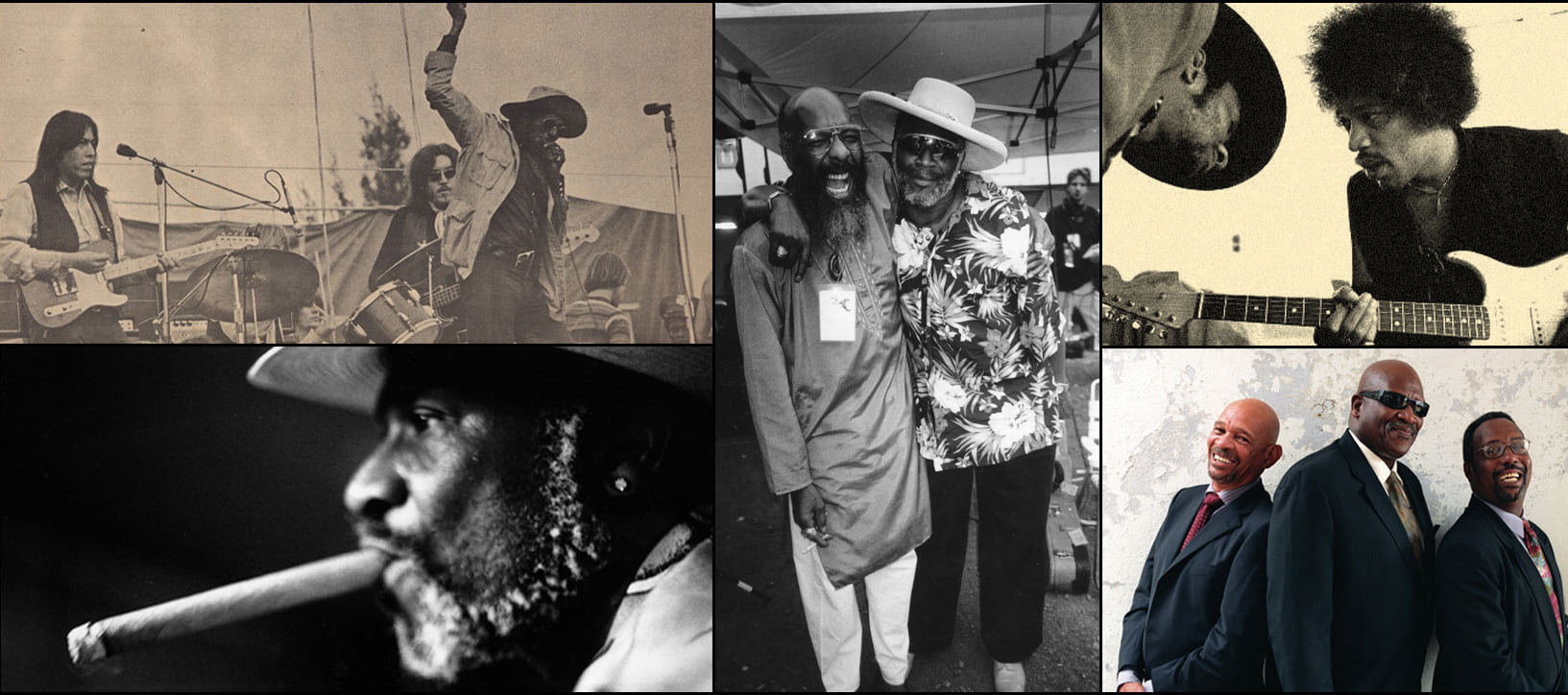

Taj Mahal is an innovator. If he didn’t work in music, it’d be easy to imagine him in a more scientific field, engineering together something uncanny he came up with only in a dream, a fleeting moment of thought that held enough weight to solidify imagination into actuality. As it is, his creativity finds shape in the only natural language that can ever truly convey meaning: music. A bluesman through and through, Mahal has redrawn that genre to reveal its full spectrum. For those purists who might take issue with the fact that “the blues” under Mahal’s thumb doesn’t keep to its strict geographical boundaries, he reveals it as a bridge to a more global experience, one that landed in the West Indies during the slave trade and traveled farther north over time. Whether incorporating African rhythms from countries like Mali and Ghana or lighter melodic fare from the Caribbean, Mahal knows no bounds. He paints, as he says, from his lineage, enlarging the picture with every brushstroke.

His newest record, Labor of Love, is a blues project with several previously unreleased Music Maker Relief Foundation artists, such as the one-armed harmonica player Neal Pattman and the blind singer Cootie Stark, who have both since passed away. Originally recorded in 1998, the album pairs solo Mahal tracks with moments of collaborative fusion. It marks Mahal’s first studio release in four years and is a powerful look at foundational blues songs like narrative ballads “John Henry” and “Stag-O-Lee” (“Stack-O-Lee” on the album). For a musician who has surpassed 50 years in the industry, his voice may sound a tad gruffer than it did at its very start, but those grains are simply wisdom he’s acquired over the years. Mahal looks upon the world — and the music in every corner — with a well-traveled perspective, always ready to draw connections between here and there, then and now.

I saw you play at the Blues and BBQ Fest in New Orleans back in October, and one line you sang has stuck with me ever since: “If you don’t like my peaches, then don’t bother me.” That feels like necessary advice in any day and age.

You can’t spend what you ain’t got, you can’t lose what you ain’t never had: That’s the blues. It runs the rainbow of emotions. I enjoy it just because of that. Whatever happens in life, the blues has got a song for it, a phrase for it: “I’ve been down so long that down don’t bother me. I’ve been down so long that up don’t cross my mind.” As far as I’m concerned, it stays solid for what humanity is at any time, so I love it.

It’s interesting that you mention an emotional spectrum, because that points toward your own approach to music, which borrows from so many different traditions.

Here’s the thing: It’s already there. I don’t think people really understand that. If you go online, there’s something called a two-minute version of the slave trade into the West, and it shows each year from when it started from Africa into the “New World.” Once you understand that, you realize that you have people from pretty near the North Pole to the South Pole who are related to one another, but don’t know one another. Okay, so where do you hear it? You hear it through the music.

For me, I was raised to be well aware of my own culture. My mother was an immigrant of the South and my father’s parents were migrants from the Caribbean, so the idea that we’re connected was there all the time as a kid. I just see it as looking up my relatives. It’s already inside; I hear it. It’s like, “How come I’m hearing Cuban music?” I like it because the Nigerians are really important in terms of what’s in there — 26 percent of my DNA is Nigerian. Another significant portion of it is Congolese and Cameroonian, and this one and that one, and hunter-gatherers and Bantu. It’s like, “Dang! You got the whole continent going on in you!” Mali, Senegal, Ivory Coast, Ghana …

So you’re singing your lineage?

Exactly. And, you know, I’m drawing from different parts. I found out what my job would be as a musician, because you didn’t just play music, it was something that was attached to value to your particular tribe, and different tribes had different ways of doing it. In one area, as a Creole, I would be responsible for the history of the family that I was attached to.

That kind of value challenges the music industry’s primary money-making goal.

They will stifle music that is really important, culturally, to a group of individuals because they’re not making money off of it. It’s just weird. So maybe, if you’re not making money off of it, make it available and let the people who need to have that have that. But no, “We’re in control now!”

That’s long been the struggle. There’s an entire history of Black banjo players that weren’t recorded because someone decided it didn’t fit a particular image.

That’s a big part of opening up these vaults that are full of incredible information.

When the muse hits, what does she deliver? And how do you transform it?

Sometimes it’s the whole song, sometimes it’s a line. Sometimes I’m walking and something comes in, and I’m listening to it. I work a lot from the bass line. I like good bass line in my songs.

That’s interesting.

I mean melodic percussion.

That’s where African music gets it right. So much of Malian music is that beautiful melodic percussion.

We started out here making walking bass — the African-Americans came up with walking bass — and the Jamaicans came up with talking bass. You listen to Bob Marley, you’ll become totally aware of bass, and what they do is they go in — the particular sound they make on Bob’s stuff — he went into the studio, after everything was done, and he would go over the bass lines with a Stratocaster guitar, because he said a lot of people can’t hear the lower bass, so you put a tone on an instrument that they can recognize that opens the vibrations of the bass up into their body and into their mind. Here’s what it does: Jazz gives you back your mind, blues gives you back your soul, reggae gives you back your body. It’s only my opinion.

I think you just came up with a new t-shirt design. I would wear that.

Well, thank you very much. You just gave me an idea.

You’re quite knowledgeable about African music. Who are the artists from the various countries on the continent that inspire you?

I listen to everything: Sunny Agaga, Sunny Adé, Papa Wemba, Franco, the Soul Brothers out of South Africa, Brenda Fassie out of South Africa. Of course, Mother Africa herself: Miriam Makeba.

So what does your record collection look like? Is it huge at this point?

It’s all over the place. I never got rid of my vinyl.

Smart.

I’m a vinyl guy. I moved into whatever it is — CDs and MP3s and stuff that I have to have — to deal with it, but for listening, it’s vinyl.

Turning to Labor of Love, I’ve heard you cover “Stag-O-Lee” before and you included another version on the album, which has a lighter, almost sweeter, feel. How do you approach these covers each time?

This version probably vibes off of Mississippi John Hurt. I don’t really think about it. These songs are living. I’m presently working with a professor, Cecil Brown, who has written an incredible book on Stag-O-Lee [Stagolee Shot Billy], and we’ve had a lot of time over the last few years to sit down and talk about this individual. He’s done an awful lot of research on him. It’s a living thing, a living person, in terms of what they do and who they are and how it goes and what they’re up to and what their life was like.

It’s this one moment that transforms into an American myth.

That kind of character existed in the community when I was growing up. He became even that much more as time went on and the communities crumbled. The area of town I lived in was one thing when we were growing up and then, when the economics changed, a lot of people moved out of the town. Well, they created the suburbs around there and the center city just fell apart. Kids growing up didn’t have the doctors and the lawyers and the principals and the school teachers all in town like it used to be. It used to be, you could see these people and you could make it forward and do something great yourself, but everybody moved away and dispersed and what was left in the inner city was the pimps, the hoes, and then it was whatever kind of drugs that were there. And then, of course, when crack hit, it just went crazy. [“Stag-O-Lee”] was an old story talking about a new problem.

Speaking about old stories talking about new problems, it feels like we’re in a time of new stories talking about old problems.

Yeah.

And, look, the country has always had a pretty backwards mindset when it comes to race, but this feels like a big step back.

If you back up, we ain’t that long out of slavery, and this country isn’t that old, and it’s built from people that didn’t really … they had some parts of it cool, but they didn’t see Tupac and Biggie and Snoop Dogg coming down the road. They didn’t accommodate for that.

I think Trump has opened up space for a certain population to vocalize what has always seethed underneath the surface.

Which may not be a bad thing. I don’t know. I’m of the opinion that, you know what, this is what people have been saying all along, and everybody’s acting like it’s so brand new. No! It’s been there all the time. You have to remember that, in the ’50s, Elvis came along touting Black music. A lot of people didn’t like him because he was a white man doing Black music, but the white folks didn’t like him doing Black music, either! But at the same time, because he did, a whole lot of doors opened, and if you follow behind him for the next several decades, Black music was the music of the Americas. Certainly in the United States. So was the poetry, so were the books, so was the art, so was the spoken word. All that was there. Almost all of that stuff has been x-acto-knifed out of our culture at this point, so you don’t really have anything that really responds to it, so these people are responding in a vacuum.

People only want to engage with people who share their point of view, so that point of view becomes reflected and nobody has to disagree.

Or learn how to agree to disagree.

Yeah, we’ve lost that.

Okay, here’s something different: My whole thing is, I don’t like Bill O’Reilly, so I had to learn how to listen to him when I don’t like what he’s saying because I was saying, “You’re reacting to him. He’s got you where he wants you. You need to respond, so that whatever he says, he says it and you respond to it. Get clarity of mind.”

It’s such an important part — to understand what someone else thinks and why.

That’s right. Who knows? We’ll see what happens. That’s why I stay with the music. That helps. It gets me through all of this. That’s why people like what I do, because it gets ‘em through it.

No matter how bad it looks, you put on a record.

There you go!

For more wisdom from the elders, read Amanda’s conversation with William Bell.

Photos courtesy of the artist.