I came to North Carolina three decades ago, as music critic for the Raleigh News & Observer, knowing very little about the state’s music. Yes, I was plugged into the college-radio end of the spectrum, from Let’s Active to The Connells, and I’d at least heard of Doc and Earl (Watson and Scruggs, respectively). But there was a lot more to it, obviously, and the joy of my career was figuring out that North Carolina’s many disparate strains — old-time and bluegrass, blues and country, rock and pop, soul and r&b, jazz and hip-hop, and of course beach music — were all part of one big story.

I tried to tell that story in Step It Up and Go: The Story of North Carolina Popular Music, from Blind Boy Fuller and Doc Watson to Nina Simone and Superchunk, based on many years of reporting, researching, and listening. It’s a story that covers a lot of ground from the mountains to the coast in The Old North State and beyond, with the likes of James Brown, Bill Monroe, and R.E.M. showing up in key cameo roles at various points.

As we’ve tried to convey with the book’s subtitle, it involves a wide range of music, from the roots music of bluegrass forefather Charlie Poole and bluegrass-banjo inventor Earl Scruggs to Ben Folds Five’s “punk rock for sissies,” super-producer/deejay 9th Wonder’s hip-hop to the Avett Brothers’ post-punk folk-rock. And what ties all of it together? Glad you asked! The narrative thread running through Step It Up and Go is working-class populism, a deeply rooted North Carolina tradition that runs into the present day. The simple detail of how to earn a living is a pretty prominent feature of each chapter, starting with the four acts in the subtitle.

Fuller (whose 1940 Piedmont blues classic provides my book’s title) and Watson were both blind men who turned to music as a way to provide for their families when few other avenues were available. Eunice Waymon’s plans to be a classical pianist were derailed and she had to start singing pop songs in nightclubs for a living, taking the name Nina Simone because she knew her Methodist preacher mother would not approve. And Superchunk is a punk band known for the 1989 wage-slave anthem “Slack Motherfucker” — and also for running Merge Records, one of the most improbably successful record companies of modern times.

Across genres, the state’s musicians have a proud, idealistic pragmatism that manifests as a certain mindset in which North Carolina is “The Dayjob State.” It’s an outlook that a lot of our state’s greatest artists retain even after music stops being a hobby and they go pro. Two of the state’s best-known Piedmont blues players, Elizabeth “Libba” Cotten (of “Freight Train” fame) and master guitarist Etta Baker, had amazing careers as musicians even though they didn’t seriously pursue it until they were both in their 60s. Pastor Shirley Caesar was even older, pushing 80, when she had a viral hit with her old chestnut “Hold My Mule.”

In the modern era, Carolina Chocolate Drops alumnus Rhiannon Giddens has run her career as a lifelong learning experience, involving academic research as well as performing, bringing long-forgotten or even unknown history and ancestors to light in the 21st century. With her creative work spanning from Our Native Daughters to an original opera score, Giddens honors her musical roots while retaining a spirit of collaboration, as many North Carolina musicians have done before her.

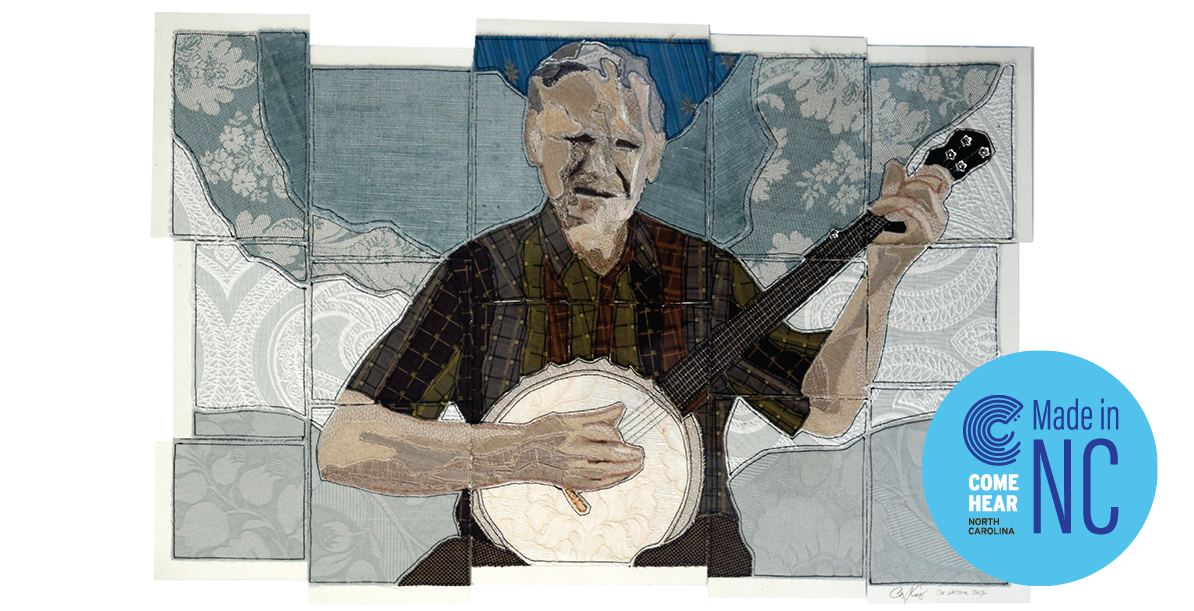

Or consider the aforementioned Doc Watson, who died in 2012 as one of the 20th century’s greatest musicians. A flatpicking legend who played guitar better than almost anyone else ever had, he nevertheless carried himself with a self-deprecating nonchalance; he just never seemed as impressed with himself as the rest of the world was. Barry Poss, whose Durham-based bluegrass label Sugar Hill Records released 13 of Watson’s albums over the years, used to express his frustration over Watson’s retiring nature and habit of deferring to other players even though there was never a time when he wasn’t the best musician in the room.

But that didn’t hurt Watson’s legacy in the slightest, and maybe it was just his way of dealing with the world. Jack Lawrence, one of Watson’s longtime accompanists, once told me that if he had been sighted, Watson probably would have been a carpenter or mechanic while picking for fun on weekends. Turns out that Doc was a homebody who would rather have spent more time at home in Deep Gap.

“Ask Doc how he wants to be remembered, and guitar-playing really doesn’t enter into it,” Lawrence said. “He’d rather be remembered just as the good ol’ boy down the road.”

Like the rest of North Carolina’s cast of musical characters, he’s remembered for that and a whole lot more.

Doc Watson needleprint, fashioned out of upholstery fabric samples by artist/musician Caitlin Cary in 2017. (Photo by Scott Sharpe.)