Cory Branan and Coco Hames lived in Nashville for years, had mutual friends, moved in the same singer/songwriter circles, released records, played shows, lived life, but somehow managed never to actually meet each other. “We would have absolutely met, if I’d ever left my house for five years,” Branan says, somewhat apologetically. “I just never go out when I get off the road. I stay at home and just look at the wife and child.”

“I never go out,” says Hames. “People are always trying to get me to go to some new bar, and I’m like, ‘I live in bars! I would rather put on some soft pants and stay at home and read.’”

Their homebodiness is well-earned, even if it’s not the only thing they have in common. Both have been road warriors for the better part of the 21st century, Branan as a solo artist and Hames as the frontwoman for the garage-pop outfit the Ettes. He writes witty, roguish songs full of concrete details and wry observations, like John Prine — if he was really into vintage synths and classic rock. Hames’s songs are minimal and smart, eccentric and rambunctious, as though she’s triangulating the spot where the Ramones, Josie & the Pussycats, and Tammy Wynette overlap.

Plus, they’ve both just released what may be their best albums to date. After the Ettes made an amicable split, she went solo with a self-titled record that shows more range and acuity, toggling between a torch song like “I Do Love You” and a country lament like “Tennessee Hollow.” On Adios, Branan writes movingly about the deaths of his father and grandparents and the ongoing trials of small town heroes like the heroine of “Blacksburg” and anyone sentenced to live in “Walls, MS.”

Neither of you live in Nashville anymore. These days, you don’t leave the house in Memphis, Tennessee.

CH: I’ll just tell you: I fell in love, got married. That’s what brought me to Memphis. I left Nashville and moved here a couple years ago, and I love everything about it. I’m very happy here. Actually, in a little bit, I’m going to go see my friend Margo Price at Minglewood Hall. I don’t know if you know her, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

CB: I met Margo, yeah, just a couple times. I’ve been back in Memphis for a whopping two week altogether. Nashville priced us out. We found a cheap place in Memphis, and it was just decided. We got the truck the day we decided to move, and we loaded up. We moved the next day, returned the truck the next day. I told my wife, “Well, it’s a new place, baby. I’ll see you in two months.” She’s already painted the whole place. She’s got it on lockdown. She’s good at moving.

Memphis has great history, but Nashville is still such a big industry city. Did it feel strange to leave that behind?

CH: I have put my foot in my mouth more than once, for more than one city. I’ve lived in New York and L.A. and London and Madrid and Nashville and Austin and Memphis. I always say something stupid about one of those cities, but I don’t really mean it. Nowhere is really home for me anyway, so it’s not really hard for me to leave. I opened a record store in Nashville, but it was getting really expensive. And my husband was visiting me, and I said to him, “What do you do when you’re an adult and you fall in love with somebody and you want to be with them?” He said, “Well, you know, you move to Memphis or I could move to Nashville.” I’m like, “I’ll move to Memphis.” So it wasn’t super weird. It’s a cool place and there’s a lot going on, but nothing I miss too much, to be honest.

CB: What record store did you have?

CH: It’s called Fond Object, and it was up in Riverside Village on the east side.

CB: I didn’t know that was your place. I’ve been up there a few times. I played behind it one time.

CH: Did you get to meet my goats and my pig?

CB: Yes. My son was fascinated. He wanted to take one home.

CH: When I was leaving, I knew it was in capable hands, so I signed off on it and gave it to my bandmates. I think they lost their lease and moved downtown.

CB: I liked living there, but it’s all the same, honestly. Mainly Memphis means geographical ease. There’s a reason FedEx is in Memphis. It has access to Chicago and New Orleans, and it’s so close to Atlanta. When I lived in Austin, you can get in to Mexico before you can get out of Texas. I do well in three or four cities in Texas. L.A., you wouldn’t think it, but it’s pretty isolated. I’m spoiled from being in Memphis. It’s really easy to tour out of. You can do two-week runs in any direction, as opposed to California, where it’s an ordeal going anywhere but the West Coast.

When I lived in Memphis, there a big Memphis-Nashville competition that everybody in Memphis knew about and nobody in Nashville had any clue about.

CB: Exactly. They didn’t know they were in the fight. I’m happy to be from Memphis, but it does give you a little bit of a chip on the shoulder. There’s no scene here. It’s splintered and fractured. There are great musicians who never leave. You can go see somebody who’s amazing, but they’re not touring very much. On the other hand, there’s never anyone in the crowd that can help you. There’s never a producer, never a publisher that’s going to offer to help your career. Nashville has that element. I didn’t enjoy that element. If you’re playing to a stubborn Memphis crowd, it burns off the chaff. If you’re not alive for it or you don’t love it, they’re going to expose you.

CH: Nashville is a hard place to feel comfortable, because I don’t think they’re really interested in anything, which feels very sad and lonely. I’d rather you dislike me than try to chat me up about who we both know. That’s the worst part of what I do. I’m not very schmoozy. I’m probably the least schmoozy person. There are plenty of people to pay for that sort of thing, but I’m not crazy about it.

CB: Don’t get me wrong — there are great things about Nashville and there are shit things about Memphis. It’s a rough town, and there’s a huge gap between the haves and the have-nots. They’re refurbishing downtown, but I don’t know if they’re working a bit on education. Nashville, on the other hand, has no infrastructure for the massive number of people that are moving there, but the city itself is a little more thirsty. They’ll go out to a show: “Oh, I don’t know what it is. Let’s go check it out.” Memphis, they need to know that their buddy is going to be there. But you can be at a party and the guitar will not come out. Unlike Nashville. Some asshole’s always pulling out an acoustic guitar in Nashville. That’s the best way to kill a party right there.

CH: That’s my cue to leave.

I wanted to ask you two about Memphis and Nashville because I feel like place figures very prominently into your songwriting. There are lots of place names in your lyrics, along with a sense of travel and movement.

CH: Cory, you can go first because you’re from here. I’m from Florida, so place has always been something I was trying to get away from.

CB: Really?

CH: I don’t know. It’s more in my record collection than it is outside my window. It’s cooler to be from Mississippi.

CB: That’s the thing. I grew up in a damn suburb. I was a little hoodrat. My grandparents had a farm, but my old man worked at FedEx. He moved us up to the last town in Mississippi, so I was just as much a suburban kid as anybody else. I grew up with the music in the church. Gospel has blues roots, maybe a little more prominent than your typical Southern Baptist reading out of the hymnal. It swings a little more. It depends on where I’m playing whether people consider me country or not. When I’m out opening rock shows or something, as soon as I open my mouth and they hear the accent, they’re like, “Oh, he’s country.” You can’t wash it off. Everything I do, it’s filtered through that lens.

But my music is all over the place. I don’t really play a particular genre. I tend to stay away from a lot of things that I love — old blues, the Piedmont stuff, that’s all scripture for me. Maybe some of the finger picking works its way in, but I don’t really play the blues or anything. I just stay away from that stuff. There’s more of a white suburban thing to me, I think. My music is more about Big Star or the Replacements. That’s sort of blues music, in a way. I’ve always said there’s a reason why Johnny Cash fans are Clash fans and Clash fans are Johnny Cash fans.

Stylistically, both of your albums are all over the map. You get a lot of different sounds and genres, but they all make sense as part of this larger musical personality that you project.

CB: Probably the last record [2014’s The No-Hit Wonder] is the closest I’ve gotten to a consistent sound. I hammered it out really fast, and they just happened to be a bunch of roots-based songs. I’m always about whatever the song sort of wants, and I don’t think as an album, as a whole. I try to structure it later, as far as the pacing of it and what songs go where. I definitely play that loose. Frankly, my obscurity lets me do that. I would probably have a bit more of a career if I didn’t change it up so much. I was on tour with Lucero, and [frontman] Ben [Nichols] was listening to Adios and he said, “Why don’t you do a full album with this kind of song and then another whole album of this kind of song?” I was like, “Because it bores me, and I don’t get to do enough albums to do that.” It takes two-and-a half-years to get a new record through the red tape.

CH: That’s true. At my level, whatever that is, I can do whatever I want, so I do whatever I want. When I was in the Ettes, it was very formulaic without me really knowing it. I was writing for this specific group of people, so of course I kept doing the same thing. There are people who are very sweet and love my band, and I’m sure they want all the songs to be just like that. But with this solo record, I wrote all the songs and let them go wherever they went. It’s all over the place. The whole point was to try these new things, and hopefully I did a good job with them.

That seems most prominent on “I Do Love You,” which reminds me of Dusty Springfield. That’s a nice thing to hear between a country song and a garage song.

CB: I get that same vibe off that one.

CH: I was trying to go for something epic, because I wrote it about my husband. I wanted an epic love story and big feelings. When I was singing it in the studio, I had my arms up like Eva Perón. I’d never really sung like that before. I just assumed I could do it. No one was telling me I couldn’t, so why not?

You’re both writing songs about real people in your lives. That songs about your husband. There are some songs about your dad and your grandparents on Adios.

CB: The one about my father, I wrote that one right after he died, and I never played it out. It seemed a little too specific. I like songs to be useful for other people. I never want to be like, “Oh, look at my pain.” But my wife told me to just shut up, play it out a few times, and see if anybody responds. She was right, as always. Since it seemed to be useful for other people, I went ahead and cut it. But usually, the closer it is to me, the more I will cast it with other characters and other situations. I’ll take all that grief and mourning or even joy and cast it into another storyline. But “The Vow” was very specifically about my dad and it seemed like it worked out all right.

CH: What do you mean? You try to put that sort of emotion or experience away from yourself? You try to insert maybe like a “he” or a “she” where it might be a “me”?

CB: That’s part of it. Also, I’m just not a fan of diary writers. When he died, I did put out a record after that [The No-Hit Wonder], and there was a song on there called “All I Got and Gone.” It’s about a guy in New Orleans and a woman, and there’s a note that he found, but you don’t know if it’s a suicide note or a “Dear John” letter. I was mourning, but I put that feeling in a completely different scenario. That song for me was like, “Okay, here we go. I got this out of me.” But no one would ever connect that, you know? I don’t tend to write with any sort of precision, while I’m still in the whirlwind. I like to get perspective on things and, if I’m going to try to do the old man justice, it’s hard to get a whole human being in a three-minute song.

CH: Yeah. Especially with something like that, do you ever feel like it’s too … I’m going through something that happened recently, and it means so much to me that it feels cheap to approach it where I’m going to put it into song. A lot of people write like that. That’s part of how they get it out, but to me, it’s so precious to me that I can’t distill it.

CB: I know exactly what you’re talking about there. Added on to all of this is that I wanted to do right by the old man and not be maudlin. I didn’t want to manipulate emotions. It’s hard to earn the genuine feeling of “Okay, this was a solid person, a human being.” The second verse is talking about how he gave shit advice. It’s got humor in there, because the old man was funny. But he was also very stoic and his advice usually amounted to, “Don’t do it.”

“I Do Love You” is obviously a very different song, but the approach is similar in that you’re writing about a real person and trying to capture that complex relationship in three minutes of music.

CH: I think everybody has had the feelings in that song. I hope everybody has. But I very rarely feel ready to immediately turn my observations or my feelings about important things into a song. It’s not something that I usually need to do, and so I don’t do it. But something that affects your life so strongly, maybe it’s okay not to write about it as a way to understand it, because it’s so big that I don’t think it’s fair for me to understand it yet. So I wait. If something strikes me or I get drunk and write a bunch of stupid lines and one of them is good, maybe it will spur something useful. That’s the most I can do and, if it comes back around and still stands up, if I still know what I was talking about, then it can make me say more.

CB: I won’t mention anybody’s name, but there is an artist I really love and respect. They got successful and found a good relationship, and then they trashed it on purpose, because they thought that’s the only one they could create. It’s the whole tortured artist myth. John Prine has my favorite quote on that: “I’d rather have a hot dog than a song.” Take the joy. You can have both the joy and the song. People say to me, “You’re a relatively sane human being now that you’ve settled down and stopped acting like an asshole, and you have kids, so how do you write when you’re happy?” Well, I know it’s all fleeting. I know all the good stuff is only here for a little bit. My fears and dreams, they go deeper and darker now that I have kids and I’m living for other people. I have no problem writing sad songs, but I take the happy while it’s there.

CH: I don’t like to see somebody who’s a wreck up on stage. I’ll be there. I’ll support them, but really I’m like, “You should take a break, man.” Because I’m not that way. If everything was going wrong and I was unwell, then I couldn’t write. I’d be so depleted and sad and wouldn’t see the point of any of it. I’m a super happy camper right now, but don’t worry, sad things will keep happening — probably as soon as I hang up the phone.

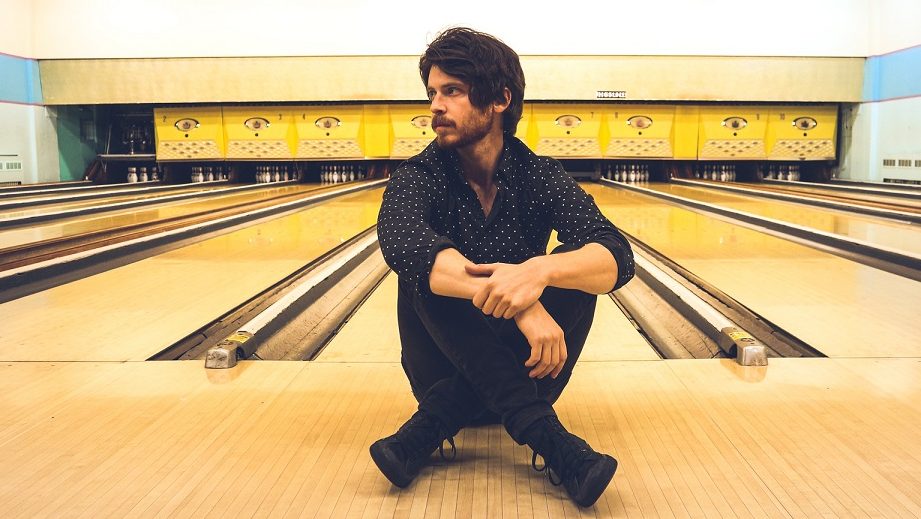

Cory Branan photo by Joshua Black Wilkins. Coco Hames photo by Rachel Briggs.