As far as voices go, Sam Beam has one of the more distinctive vehicles within indie folk. It’s been hailed as “intimate,” “unadorned,” and — interestingly — “limited,” the latter description coming from an earlier observation he shared with The New York Times in 2013. If Beam saw his instrument as constrained, that might have something to do with the now-infamous story about his first album as Iron & Wine, 2002’s The Creek Drank the Cradle. He recorded it in a hushed basement setting so as not to disturb his slumbering daughters overhead, constructing a degree of restriction that set the stage for a voice stronger because of such boundaries.

Beam’s curiosity about other, fuller sounds and musical genres eventually meant a need — if not a desire — to push his voice in bigger ways. His 2007 album, The Shepherd’s Dog, featured a full band and sped past the quietly recorded acoustic style on which he established his name. Each subsequent album thereafter endeavored to further that exploration, featuring instrumentation that included — at turns — horns, strings, and other layers. But as those songs and their arrangements required larger and louder realizations, so, too, did his voice. In between moments where the music supported his capability and capacity as a singer existed those where he stretched and strained beyond his established limitations.

With his new album, Beast Epic (his first since returning to Sub Pop), Beam has hit upon more than a few realizations, least of which is that his voice isn’t so much limited as it is abiding by its own restrictions. Call it a glass half-full perspective. “It’s really only comfortable in certain types of things,” he quietly explains. “You can do anything around my voice, but it’s kind of this elemental force. Not to toot my own horn or anything, but it’s grumpy; it doesn’t want to move. That’s something I learned to stop fighting and enjoy.”

He arrived at that understanding through the two projects that fell in between his proper Iron & Wine releases: 2015’s Sing into My Mouth with Band of Horses’ Ben Bridwell, and 2016’s Love Letter for Fire with Jesca Hoop. “She let me enjoy my voice again,” he says about his creative collaboration with Hoop. “It’s been asked to play roles in a lot of different songs, but the partnership with her and the one with Ben let me enjoy my voice for what it does and not what it’s trying to be outside of that.” Beam keeps to his dusky, whisper-like revelations on Beast Epic, but finds moments to loose his vocal capability and showcase its constrained magnitude. In “Bitter Truth,” a song chock full of exactly what its title purports, he climbs to an emotional apex — a kind of curbed exasperation — before sliding back down into his trademark resigned sigh. In “Song in Stone,” he holds on to syllables, allowing his voice to shape the words rather than the other way around. Throughout the album, his vocal confidence and the resulting coziness have never felt so palpable.

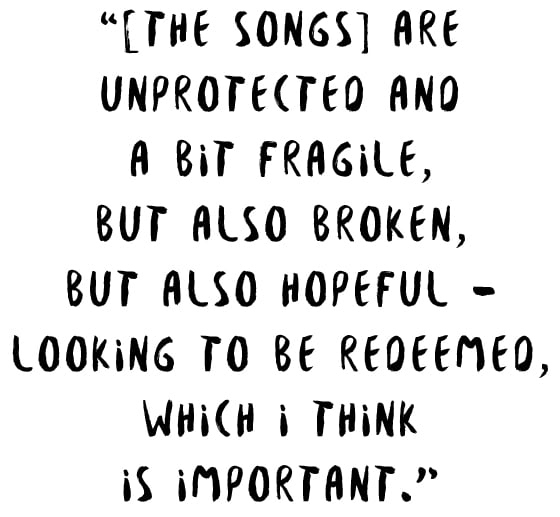

As assured as his voice now sounds, the songs on Beast Epic pang forth with questions. Getting older has brought perspective and wisdom and all those traits that supposedly come with age, but there’s still room to screw up, and Beam remains almost painfully aware of that potential across the album’s 11 tracks. “You never stop learning. You never stop fucking up. You never stop wanting,” he says. The album looks at mistakes both committed and experienced, wondering aloud about the forces that bring people together and push them apart again. “It’s a middle age kind of record, where you’re still surprised to be dealing with the same things in life — getting hit with the same blows and, also, finding the same hope around the corner,” he explains. “[The songs] are unprotected and a bit fragile, but also broken, but also hopeful, looking to be redeemed, which I think is important. Looking to do the right thing, or looking for what the right thing is.”

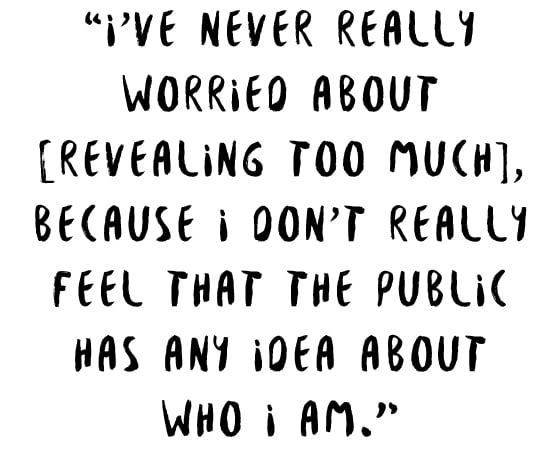

He doesn’t have the answers at the ready, but his ongoing search provides for some potent imagery. Beam’s poetic wordplay has always danced around specific meanings, creating robust pictures that allow listeners to do the work of interpretation rather than laying it bare like other confessional songwriters might. Don’t be fooled: Beam is as confessional as they come, but he cloaks his revelations so they’re not so easily parsed out. “I’ve never really worried about [revealing too much], because I don’t really feel that the public has any idea about who I am,” he laughs. “I think people assume the songs are more about me than some of them are, and don’t know when I’m being more revealing. I always sorta held those cards close. Most of them are saying, ‘I wish I had given more love when I didn’t.’ Those kinds of confessions are easy and important for me.”

That Beast Epic sounds closer to earlier Iron & Wine fare is the circuitous route result of marrying his earlier hushed-whisper stylings with the full band arrangements he began exploring in The Shepherd’s Dog. Then, too, there’s the touch of whimsy that distinguishes his latest effort. Working with Hoop allowed Beam to tap into his playful side. To put it mildly, he’s got a wicked sense of humor, but that doesn’t surface throughout his lyricism so much as through his persona on stage. When Beam and Hoop toured together for Love Letters for Fire, their witty repartee interspersed the affective affair with a much-needed comedic release. But he hasn’t found a way to inject that sense of levity into his often-brooding lyricism. “Beyond the music, I feel like the jokes are part of my everyday, and they come and go,” he says. “When I sit down to write a song, I want to make something that lasts. Even if it’s off the cuff, I want it to be that you can’t laugh off. Maybe it’s because I find it easy to laugh everything off.” He pauses, before adding, “It’s so strange because there are so many songwriters that I like that are really funny, but for some reason it doesn’t play into what I do.”

Beam’s levity shines forth from the album’s instrumentation and arrangements, which yield a greater sense of playfulness than in albums past. Describing the recording process in Beast Epic’s press release, he wrote, “We spent about two weeks recording and mixing and mostly laughing at rhe Loft in Chicago.” That laughter arises in many different tracks, but most assuredly on “About a Bruise.” Beam contrasts the song’s heavy-handed lyrics (like “Tenderness to you was only talk about a bruise”) with a flurry of plucky, rhythmically driven additions like piano, harp, and more. Then there’s the carefree “woo-hoo-hoo” he unleashes shortly after the midway mark. It bubbles forth almost unconsciously. “I like to have fun. The music can be kinda heavy,” he chuckles, self-deprecatingly. “I think it’s important to have some balance.”

It’s not that Beam has cauterized whatever exploratory impulse drove his earlier albums, but that, with Beast Epic, he’s been able to take all the many and sometimes seemingly disparate parts of his career and piece together a project that feels mature, assured, even while echoing with questions. “This one was more about taking the journey so far and presenting everything that I’d learned in a really relaxed way,” he says. “I just sorta let go of the reins, and this is what came out.”

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.