The Ghosts of Highway 20 may sound, in title, like it has traces of wanderlust, but the ideas behind the 14 songs on Lucinda Williams’ latest record find their weight in where they come from rather than where they’re going. In many ways, Ghosts is a record that honors Williams’ father, poet Miller Williams, with opening track “Dust” its most obvious but certainly not its only homage. The song is her second re-imagining of one of Miller’s poems, expanding on his composition of the same title after finding success with a similar endeavor on 2014’s “Compassion.”

“[‘Compassion’] was not the first time I’d tried to tackle it. I’d been, for years and years, wanting to take one of his poems and turn it into a song, but I hadn’t been successful at it — it’s really quite challenging,” she says. “When you sit down to do it, you realize the difference between poetry and songwriting. You can’t just take a poem and slap a melody onto it. You have to take the lyrics and rearrange them into something that looks like a song.”

“Dust” is the only track on The Ghosts of Highway 20 that directly stems from the poetry of her father, but the record is filled with glimmers of his influence. “If My Love Could Kill,” a gut-wrenching glimpse into the pain of watching a loved one grapple with Alzheimer’s, directly draws from her father’s battle with the disease. But Ghosts isn’t limited to honoring Lucinda’s roots alone: There are fathers and grandfathers and brothers and sisters whose stories fill the lines of the expansive record, too. Bruce Springsteen’s “Factory,” the record’s lone cover song, finds its meaning in Lucinda’s father-in-law, who spent over three decades working in the factories of Austin, Minnesota.

“First of all, it’s a great song. I love doing it. But, also, it’s sort of a tribute to Tom's [Overby, husband and manager] dad. It’s a short, just really sweet song that’s very concise,” Lucinda explains. “It says so much in so few words. The line that I love is, ‘They walked through the gates with death in their eyes.’ I remember Tom saying to me, ‘I’ve seen that. I saw the men walking out of the factory. I could have been one of them.’”

It’s a haunting image, and one that isn’t a far cry from the fire-and-brimstone billboards and desolate stretches of road that set the tone for the entirety of the record. “Every question and every breath, every exit leaves a little death,” she sings on the album’s title track. Highway 20 weaves its way through many of the towns in the South that have held memories for Williams, so much so that the fascination with its reach began when she was naming her label, Highway 20 Records.

“I was looking at this map — I think Tom and I were talking about different towns in the South — and I saw Highway 20 and all the towns that it was running through,” she says. “It runs through all these towns where I grew up. My brother was born in Vicksburg, Mississippi. My sister was born in Jackson. I started school in Macon. Monroe, Louisiana — it also runs all the way through there.”

The exits that dot I-20 played host to some of the more formative experiences in Williams’ life, from growing up to experiencing music and, later, finding familiarity amidst a life of back-to-back shows and endless touring.

“I went back to play in Macon, Georgia, a few years ago at the old Cox Theatre in downtown Macon, which is one of the first places the Allman Brothers got started,” says Williams. “It’s this really cool little theatre. I hadn’t been to Macon, been back there, in however long, and I remember it amazed me how little had changed. It’s one of those Southern towns that, unlike places like Nashville that are kind of ‘boom’ towns right now, one of these towns you go back and hardly anything’s changed.”

Williams started elementary school in the small Georgia city and, even in those early years, her father was exposing her to art and music in its natural environment.

“One of the reasons it’s so significant for me is that I remember my dad taking me to downtown Macon to see, back then, this blues — gospel blues — blind preacher street singer guy named Blind Curly Brown. He never got real well-known or anything,” she says. “Needless to say, that was a significant moment because there I was, six years old, listening — that’s seeping into my little six-year-old mind.”

Williams tagged along with her father often during that time period, even chasing peacocks on the estate of his great mentor and friend Flannery O’Connor and, ultimately, finding O’Connor’s work to be a jumping-off point for her own. Songs from throughout her career — the vivid, dark imagery on 2003’s “Atonement” or the symbolism in 1998’s “2 Kool 2 Be 4-Gotten — exemplify the way Williams’ art was informed by the classic Southern writer. On Ghosts, this reveals itself in tracks like “Louisiana Story,” a tale of abuse masked in Southern idioms. Meanwhile, “House of Earth,” a song with borrowed lyrics from Woody Guthrie, continues Williams’ tribute to her influences in a tangible way without sacrificing her own distinct voice.

“I was actually sent those lyrics,” remembers Williams. “[Nora Guthrie] sent me the lyrics to [“House of Earth”]. She said, ‘You know, the lyrics are not your average Woody Guthrie lyrics, and I thought of you when I was trying to think of who might want to try to put music to them. I thought, if anyone can do it, you would be the one to do it.' So I read them, and at first I went, 'Wow.' Especially for that time — it was written in the ‘40s — it’s basically about him visiting a prostitute. It’s pretty liberal thinking, especially for that day.”

Nora was right, though: If anyone was up for the challenge, it was Williams, who went on to perform the provocative number at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C. before eventually recording it for The Ghosts of Highway 20.

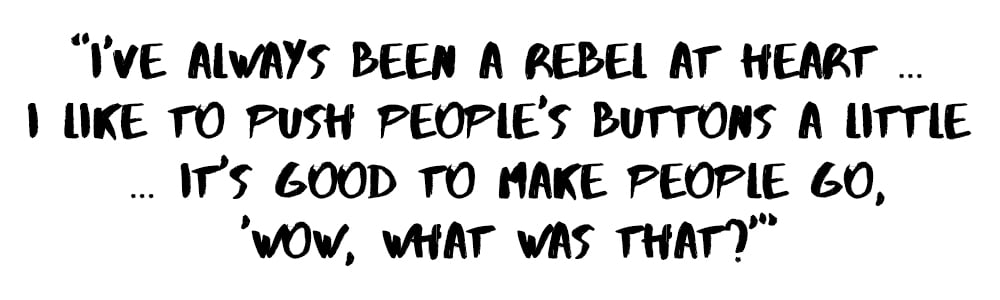

“One of the things my dad taught me as a writer was to never censor yourself,” says Williams. “I’ve always been a rebel at heart, so I think I like to push people’s buttons a little. I like to make people think, like any good artist does, I think, whether it be a painter or a songwriter. I think it’s good to make people go, 'Wow, what was that?'”

The Ghosts of Highway 20 was largely recorded along with songs from Williams’ last record, 2014’s Where the Spirit Meets the Bone. Working with the intention of releasing it via her own label — and producing the record with her trusted team at the helm — helped her to solidify which songs were a fit for the unconventionally long record.

“I feel secure,” she says. “It makes me feel secure if I’m working with people I trust, and I think that’s the bottom line.”

Williams’ tranformative work on songs like “Dust” or “House of Earth” makes for its own road map of the way art can reimagine itself, paving a formidable road for artists of a new generation to look back on her work for their own cues. In many ways, Lucinda Williams’ creative output mimics the unwieldy stretch of road that’s borne witness to it; like an expansive Southern highway, the best records are never really finished being explored.

Lede illustration by Cat Ferraz.