Born on July 4, 1942, it seems rather poignant that this musical ambassador of freedom and exploration came into this world on Independence Day. First emerging onto the national scene in the early 1960s as a member of Bill Monroe’s Bluegrass Boys, Rowan was a young buck — a “green horn,” as he’d say — who found himself alongside the “Father of Bluegrass,” singing lead and playing rhythm guitar.

And though Rowan and Monroe were very different people from equally different backgrounds, there was a deep, mutual love and respect for the sacred art form that is music — either learned, recorded or performed live — where lessons and anecdotes spun by Monroe decades ago have remained written on the walls of Rowan’s memory and throughout his extensive melodic travels.

The second half of our conversation hovers about the road to the here and now, about nothing and everything, and anything in-between, which is just how Rowan has always carried himself, that signature glint of mischief in his eyes radiating hardscrabble sentiments of a life well-lived.

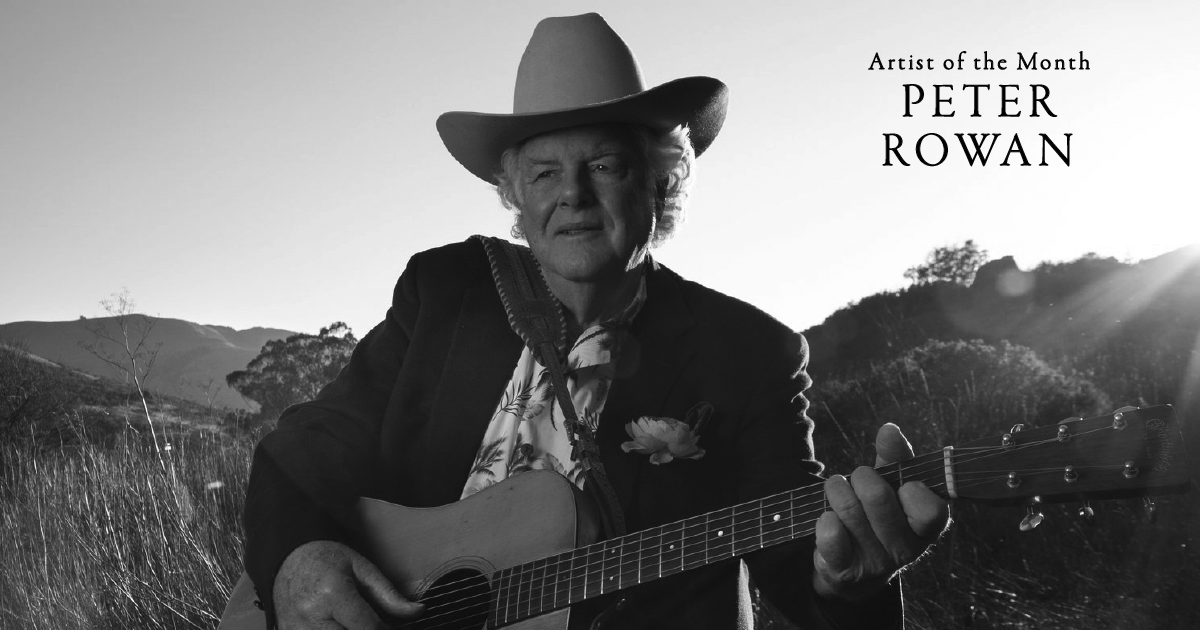

Editor’s Note: Read the first half of our interview with BGS Artist of the Month, Peter Rowan.

When you think about getting older, what are your reflections on your relationship with Bill Monroe — as a musician and as a mentor to you?

Rowan: I’m just taking what he was doing a little further — that’s all. He said, “Pete, don’t go too far out on the limb, there’s enough flowers out there already.” He saw me coming. And his mentorship is just something that’s part of me.

Which you’ve parlayed into mentoring other people.

Yeah, I’m at that point. I remember what Josh White and John Lee said to me as I nervously presented my playing to them — “take your time, take your time.” The bluegrass guys, [fiddlers] like Tex Logan and Kenny Baker, were the touchstone of bluegrass at the time. Any jam session was led by the fiddlers, and then you’d throw a few songs in. But it was the fiddlers — Buddy Spicher, Richard Greene, Kenny Baker, Tex Logan, Vassar Clements. It could be five fiddlers and they’d all play that tune. That’s what the jam was, it was playing fiddle tunes. It wasn’t like, “Okay, you take a chorus and just play.” You stayed within the structure.

By the way, this whole idea of jamming, there’s always that element in the jam where you go to sort of an unknown place. There’s a real artless art to that. And I’m not sure the bluegrass folks are going there, because most of their instruments are short duration notes. It’s not like a saxophone where you take a breath and just blow for eight bars. But, I have to say the fiddle player for the Steep Canyon Rangers, [Nicky Sanders], he’s taken it up [a notch] — he’s paid attention to Vassar.

When you look at all of the musicians you came up with in the 1960s, there’s not a lot of them left right now.

It’s me and Del [McCoury].

That’s about it. And maybe Bobby Osborne.

Bobby is still alive, and I’m so glad I got to record with him a few years ago for Compass [Records]. And there’s David Grisman.

In terms of touring, you and Del are the ones that are always out there, onstage and on the road.

Yeah. Well, I think it’s part of the gift of being able to indulge in the thing that gives you the power to sing. You can have a lot of afflictions. But if you can sing, you can overcome. The weight of age. For instance, I saw Del last summer. We played out in Colorado, and there’s this picture of us — we look like we’re 10 years old. Just laughing and smiling, well, because it is a joy.

Both of you have never lost that childlike wonder of creation and discovery. You’ve always retained it.

Yeah. But people who want to say Del is upholding the tradition? Yes — stylistically, musically — he is. But he’s doing Richard Thompson songs. Del’s not close-minded.

You’ve always had this core of tradition, but you’re never shied away from jumping the fence into other genres.

And I’ve been criticized for it. Going to Jamaica and recording reggae with bluegrass songs. Going to Texas and recording with the great Flaco Jimenez. Come on, these are masters of our world — how could anybody in their right mind not do what I did? Bluegrass Unlimited once referred to me as a “schizophrenic musician,” like it’s a mental thing, where “he’s gone off the deep end.” [Laughs]

The criticism you faced is like what Billy Strings is facing today, and what Sam Bush faced in the 1970s. It seems every 20 years or so, the critics always say the sky is falling in the world of bluegrass. But it never does. It remains.

I think that goes back to Bill Monroe. He said this [to me], “If you can play my music, you can play any music.” That goes for Billy [Strings], too. And [Bill] saw it, where maybe I didn’t see myself as that. [Growing up], I had my little rockabilly band The Cupids, and I learned some Lead Belly tunes, trying to learn Lightnin’ [Hopkins] tunes. And here’s Bill Monroe, and it’s perfect. There’s harmony. It’s hard-driving. There’s acoustic guitars. It’s got everything I wanted.

You’ve had this incredible life — traveling the world, meeting people, collaborating onstage and off with all these musicians — what has the culmination of all of those experiences thus far taught you about what it means to be a human being?

Well, you know, all of these players were always the ones that didn’t have any prejudices. You sit down with Lightnin’ Hopkins and he doesn’t care. He’s not like, “Oh, white boy wants to steal my music.” These guys were musicians, and they weren’t just your average person.

I lived in the South long enough to have tremendous respect for the amount of heart that the Black people down in the South had. People who lived through the hard times and were glad to be driving a cab to get you to the airport, [where] you shake hands with that man — his hand is warm, just warm love and compassion in that hand. During those years — the 1960s — when it was still segregated in the South, it was weird, this thing of love and theft.

I was with the Bluegrass Boys and I remember one night we played the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. Mance Lipscomb was on the bill. He came back and we’re all sitting around the dressing room. I asked Bill and Mance if they would play together. You might see [something like] that at Newport [Folk Festival], maybe. But mostly it was segregated into different musical styles [at that time] — Cajun, blues, bluegrass. I said, “Would you guys play?” And they didn’t know what to play. Bill goes, “What do you want us to play?” Bill didn’t know what to play. He didn’t know the starter blues. And Bill just started playing, and Mance played along, too. But it wasn’t this moment that I had imagined, like this intergalactic grandeur, you know what I mean?

[Bill and Mance] were really specialized in their own world. Mance Lipscomb, his music was complete, his version of the blues. Bill Monroe’s music was complete, his version. But [Bill] would talk about his “other music.” He’d say, “It wouldn’t have a dobro, but it might have a slide guitar.” I’d say, “And a mandolin?” He’d say, “Maybe not a mandolin, but maybe one of them little guitars.” [I’d say], “Like a what? A ukulele?” I think his “other music” was the mellifluous laidback music of a Hawaiian feel. Slow. Because bluegrass was all about keeping it up, playing for farmers who were exhausted, folks that had been up since 4:30 in the morning, go to a little schoolhouse and see Bill Monroe. He said he wanted to give them something that would raise their spirits.

And the world changed while Bill was alive. Typically, he would steer away from anything that compromised him. He began to understand that his position was not that of a star so much as [he was] a progenitor of musical tradition. He took from many different things — blues, gospel, Celtic. And he alone had figured out a way to put it all out there, soon to be copied by many, many others. And the talent of those others were helping him develop his style — Earl Scruggs, Lester Flatt, Don Reno, all those folks.

(Rowan pauses for several seconds, seemingly lost in thought at the initial question posed.) What are you thinking right now?

Well, I’m not really thinking very much. [Laughs]. But I want to make sure that we’ve covered some of the things that you’re asking.

Well, you’ve lived the life of an artist. What is that life of an artist, and why is it that was the path you ultimately chose?

Okay, this is the connection now. When I was four years old [in 1946], my Uncle Jimmy came back from the Navy. He’d been in the South Pacific [during World War II] and he brought back grass skirts and coconut bras, all this tourist stuff because he’d been stationed in Honolulu, Hawai’i. I remember the first musical experience I had was Uncle Jimmy dancing around our living room [in Massachusetts] in his skivvies with his sailor hat on playing the ukulele and singing “My Little Grass Shack in Kealakekua, Hawai’i.”

I guess that just seemed like such a happy thing, you know? That was so different from what was the norm. After World War II, they were all celebrating. But Uncle Jimmy was saying, “Hubba, hubba, ding, ding,” all these strange things. Well, [later in life], I went to Hawai’i and traced Uncle Jimmy’s footsteps. I found out he [used to hangout] at this hula bar called Hubba Hubba. He had absorbed what he could — during the middle of World War II — some of that inspiration from the Hawaiian aloha spirit.

And that’s in you. I know that’s in you, too.

Yeah. So, when Bill Monroe was talking about his “other music,” I think he was talking about Hawaiian music. Because his song, “Kentucky Waltz”? The melody of that song was recorded in 1915 in Honolulu by John Kameaaloha Almeida, this Portuguese-Hawaiian orphan, who was adopted and raised by a Hawaiian family. He had a really strong band. A lot of the younger singers of the 20th century went through his band as featured singers, and he had three girls singing harmony. So, when Bill Monroe had a hit with “Kentucky Waltz,” he was singing a melody that came from Hawai’i, probably a classically derived melody. There’s this strange sort of admixture of technique and heart, you know? And that’s always been my path.

I feel like, maybe subconsciously, that memory you have of your uncle is what you’ve been chasing after your whole life.

I think I’ve been wanting that coconut bra and grass skirt again, man. [Laughs].

Photo Credit: Amanda Rowan