Pop and rock performers of mainstream and indie varieties alike, and their promotional teams, tend to make a production out of explaining sudden embraces of stripped-back production. Often, they spin tales of artistic ennoblement — of Justin Timberlake and John Mayer escaping the glossy trappings of their home genres to do soul searching in more pastoral musical settings; of Kesha and Lady Gaga staking their claims to singer/songwriter approaches that seemed slightly more grounded and organic than the club bangers of their pasts.

They temporarily tether themselves to seemingly sturdy, sincere, rooted approaches, and enlist musical guides and collaborators knowledgeable in those lineages. Even Beck, one of the leading postmodern shape-shifters of the alt-rock era, treated venturing closer to folk as a means of trading a reliance on irony for reflection, and Thurston Moore, long associated with the artfully discordant squall of Sonic Youth, consciously personalized his songwriting approach on an acoustic project that Beck produced.

Stephen Malkmus, whose bristly, brainy 1990s indie rock band Pavement was a distant descendant of Sonic Youth and a contemporary of Beck, isn’t at all oblivious to the fact that there are scripts for lending meaningful context to newly cultivated folk leanings. But Malkmus has carried his slouchy, self-deprecating demeanor into his 50s, and it’s his style to be amiably noncommittal. He’s ventured down the acoustic road himself on an album helmed by Chris Funk of the Decemberists and Black Prairie and wryly titled Traditional Techniques. Coming from Malkmus, that’s not meant to come off as any sort of claim to mastery.

He’s used to being interviewed by general interest outlets, not roots-versed ones, so he tries to temper expectations right off the bat when speaking to BGS, describing his knowledge base of folk forms as “sort of a crude appreciation.” He even tries a bit of deflection: “Chris, who I did the record with, he would be able to speak on more levels than me, you know?”

In reality, Malkmus’ catalog with Pavement and his subsequent band the Jicks betrayed flickers of folk interest. He’s admiring of Bert Jansch’s ’60s-era guitar innovations and appreciative of the Nickel Creek cover that introduced his songwriting to the virtuosic string band pop scene in the early 2000s. And he’s playing his 12-string more than ever.

The 10 tracks he recorded with Funk, bolstered by the contributions of guitarist Matt Sweeney and Qais Essar, renowned player of the rabab (an Afghani cousin of the lute), are accomplished and expansive. Malkmus’ sublimely oblique, thoroughly contemporary meanderings easily merge with spry, spindly rhythms and gently psychedelic interplay. It’s an experiment that paid off, and he stepped away from helping with his kids quarantine homeschooling to offer his measured musings on the making of it.

BGS: In the official narrative around this album, you make its origins sound happenstance — as though you were recording a different kind of project with Chris Funk and happened to get distracted by the acoustic instruments he had lying around.

SM: That’s somewhat true. But I did get into the 12-string guitar. I have all these dad images: “If you try one drug and then you try a pure, stronger version of it, you never want to go back.” That’s what it kind of feels like with the 12-string guitar, going back to the 6-string. Once your fingers get used to it, it’s just chiming and you’re hearing all these overtones. During this bunkering, I’ve been playing a lot.

You’ve downplayed your folk literacy, but I can hear at least a general interest sprinkled throughout your catalog in songs like “We Dance,” “Folk Jam,” “Father to Sister of Thought,” and “Pink India.”

Yeah, that’s true.

What music were you acquainted with in a British folk-rock or psychedelic folk vein that felt relevant to what you wanted to do?

Richard Thompson and the Fairport Convention, the whole British world, and also Bert Jansch that was a huge influence on Led Zeppelin and Fairport Convention. The English tradition, those kinds of spartan arrangements that were kinda catchy too. I guess I like catchy things. I was coming from a Beatles world, like, “Fuck, that’s getting in my head, that melody.” I also felt with the pickers of England, Richard and Sandy Denny, I would hear something catchy in there and grooving. There was, like, a groove.

In some other interviews you’ve mentioned Gordon Lightfoot as a vocal touchstone.

Oh, I love him.

But there were a couple of performances on Traditional Techniques that made me think less of Lightfoot and more of Beck’s Sea Change, like the calm, composed way you sing “Flowin’ Robes.” It made me wonder whether you learned anything from acoustic forays by your alt-rock peers.

Even the first song, “ACC Kirtan,” I thought it back on that one, just because it’s kind of slow and probing. It might be [Beck’s] Mutations instead of Sea Change or something. On all his acoustic albums, he had big world music vibes to it that I could see him jamming out, like throwing a sitar on there or something. Those albums by him, they’re super rich and high fidelity and beautifully recorded by Nigel Godrich. But I guess I don’t really think of those contemporaries when you’re making music at the same time.

How do you relate to the ways that rock or pop musicians’ excursion into folk-leaning forms are presented as personally significant moves, like they’re stripping away the noise and gloss and baring their souls, getting in touch with their roots?

That’s a classic way to see it, right? And also it goes with the sounds; it’s quieter, more direct, versus just naked or whatever.

Everything sort of happens quickly with me. I’ve said a couple times in some interviews, in the back of my mind I always wanted to play an acoustic record of some sort. I just didn’t know how or what to do. I wanted to do it because I thought people would like it too. It wasn’t only just ‘cause I was dying to do it. I also think about what I wanna release and what people might be interested in, and what I think I might be good at, of course. There’s no doubt that I’d think that most people have already heard me that are gonna buy the record. They would like to hear, “What would Steve do in an acoustic environment?”

And of course, we wanna surprise people and do it differently. If you imagined it in your mind, you might not have thought that it would have standup bass and Afghani-American guys playing eastern instruments. We’re sort of aware, or at least I am, of having a little bit of a risk, something gambled, besides not only that you’re just playing quietly. Putting yourself where you’re in a position with people you don’t know; we don’t really know how it’s gonna sound, a little more like a jazz situation in some ways. I didn’t really know what people were gonna play, but I had some rules for Chris and I, which were that we were gonna play it all live in the studio, and the drums were gonna be real quiet, and the bass too.

How much of the album would you say reflects you adapting to or embracing different musical forms and how much is you just framing the thing you do differently?

In the end, for better or worse, I feel like it’s just me putting a version on what I do. Because if you’re just self-aware, what is it really but that? When you’re writing the songs, you can imitate other people in your mind. There’s a lot of that going on. As you run through different ways to approach a riff, you’re usually thinking of not of yourself at first: “This kinda sounds like Led Zeppelin or PJ Harvey,” real basic broad strokes. Then I riff off that. I try to think of the best way. And also in the communal [setting], listen to other people; it’s really important to not have stuck to your own thing.

I’ve gotten the sense that people coming to this music with a working knowledge of your catalog with Pavement and the Jicks find some of these songs, like “What Kind of Person,” to be softer or more sentimental by comparison. Did you think at all about the kinds of tones that people tend to associate with singer-songwriters and folk songs?

Well, I would be thinking that there’s some really deadly serious lyrics about not only “my heart was broken,” but “I’m a poor man that died tragically or whatever and it sucked.” Most of the English ballads are really sad material. You can look at them in a Marxist way or something and say these people were screwed from the outset. I think of folk songs like that, but I also think of Michael Hurley and freaky geniuses like him playing acoustic music in a small bar to stoned people, and it’s not really deadly serious. Sometimes it is for a second, and then it’s funny, or we’re just being together making music, lower stakes. When I say low stakes, the stakes are as simple as just playing with some people in a room, like conjuring up music together, lyrics. Maybe you’re doing them to make the guitarist to your right laugh for a second, rather than make a song for a mother who lost her child young. You know what I mean? [laughs]

You’re talking about the tragic ballad tradition, the stuff that people think of coming over from the British Isles. The modern folk singer-songwriter movement has its own set of expectations in terms of tone and perspective.

Newer stuff, I don’t listen super closely to lyrics or what people are singing about, but it’s usually about love gone wrong.

Wait, you don’t listen that closely to lyrics in general?

Yeah, not really. Sometimes. It really depends. Most things I only listen to once or twice, for better or worse. Of course, other things I dig into super deeply. It’s probably to the detriment of my songwriting or people that like super-tight stuff. A line pops out and I’m like, “That was fuckin’ awesome.” It has to be set up by other things in the song. It’s not like you can just say that line with absolutely nothing around it. I’m more like I hear it in a song, or the way a person sings it, and I love it, rather than looking at it on the written page or thinking of it as just lyrics.

You seem to have a healthy amount of self-awareness about being a musician known for one thing, moving into a different lane.

It’s not only what I think, but also when I played it to other people before I put it out, I listen to others who say, “I like that one.” Or, “Why do you want to release that?” So it’s not only self-awareness but being self-aware enough to ask other people what they think. I think for all musicians, there are certain songs we make that we really like that other people like less. [Laughs]

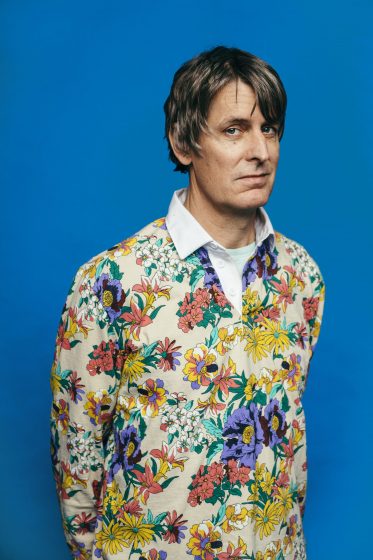

All photos: Samuel Gehrke