Two guys with acoustic guitars singing quietly — it’s not as easy as it looks. For the Norwegian acoustic duo Kings of Convenience, a lot of forethought went into the simplicity that shines through Peace or Love. Because it is sonically spacious, the album feels like a respite in an increasingly loud world. The comforting vocal blend, the lilting melodies, and concise songwriting are all wonderfully intact, carried over from their prior project a dozen years ago.

With impeccable rhythms and an eye for detail, the collection feels cozy and even encouraging at times. But upon listening closely to the lyrics, it’s clear that band members Erlend Øye and Eirik Glambek Bøe are no strangers to conflict. Note the album title: It’s Peace or Love, without an “and” in sight.

Plus, there’s a rough imagery inherent in a title like “Rocky Trail,” the album’s sprightly lead single that finds the narrator admitting to missing the warning signs in a relationship and wishing for another chance.

“‘Rocky Trail’ represents a certain kind of groove that we do a lot, which is of course inspired by bossa nova,” says Øye, speaking on behalf of the duo for the first half of a Zoom interview with BGS. “It features Eirik’s trademark technique. He has a very specific technique of playing that allows him to be as quietly funky as he is. I think it is also quite layered, like onion shells. There are a lot of details in that song, so I think it rewards recurrent listening.”

For example, one can hear a propulsive rhythm in the verses, not unlike the one-foot-in-front-of-the-other mindset of a challenging hike, and then in the middle there’s a downward glissando that makes it feel like this relationship just tumbled back to square one. Or is that overanalyzing?

“Hmm, I wish I had thought of all that,” Øye says with a laugh. “Coincidence!”

While both musicians have a number of side projects, Kings of Convenience have always managed to come back around. Asked about finding common ground in the music they enjoy, Øye says, “Although we think of ourselves as very different, in reality being together all those years – although we didn’t always hang out together all the time – we influence each other a lot with all the music we’ve gone into.”

He continues, “Just as an example, when Eirik started coming around with these bossa nova ideas, that was already in the first year of us working more or less like Kings of Convenience in ’98. My first reaction was, ‘Oh noooo. What is this elevator music?’ But then, you know, that’s how you grow, by accepting something you have a preconceived notion of. I’m recently playing a lot with some Italian friends of mine and they are particularly inspired by Latin American music, in addition to Italian music. So, just following them, trying to pick up what they do, that’s how you get inspired – and I bring that into Kings of Convenience. Without knowing it, you inspire each other.”

When the topic turns to country music, Øye says he once read an interview with R.E.M.’s Peter Buck about playing country sessions and finding different ways of getting from G to F to C. “I remember thinking that’s interesting,” he says. “I do like this aspect of country music, basically trying to dig even more around an already very dug place, and not being afraid of that. OK, it’s not the first song in the world that goes F, C, G, but that’s not so important. I think that’s the one division in Kings of Convenience where we still disagree, that I’m more sympathetic to the country music side of making music, while Eirik is very into the idea that a chord progression should be unheard of.”

But will that ever get resolved?

“It doesn’t have to be resolved,” Øye concludes. “It’s part of our ongoing creative dynamic.”

That dynamic is much more complicated to capture in a studio than one might expect. Anything from the age of the guitar strings to the length of one’s fingernails can derail a session. That’s part of the reason Peace or Love was recorded over the span of five years and in five cities, almost always in person.

About to explain how they finally got the best version of “Rocky Trail” after many, many attempts, Glambek Bøe pops up in the Zoom call. After some cheerful greetings, Øye teases that “my main contribution to that song is the end part, with the guitar solo, and also my contribution is my incredible patience of recording the song so many times!”

Recreating the scene for comedic effect — “This is going to be the one, I promise you!!” — Øye graciously signs off, ushering Glambek Bøe into a conversation about the songwriting component of Peace or Love, specifically the encouraging messages nestled within some pretty sad songs.

“A lot of our songs are sad and they bring people in touch with their sorrow,” he says. “So I wanted to also give some uplifting words sometimes. I mean, once we’ve made people sad with our sad songs – when we have their attention – it’s a nice moment to give them a little pat on the back and a piece of advice. I like that type of songwriting, which is actually advice writing. You’re writing down advice for people. And for me, some artists have been giving me advice throughout my childhood and my young years, especially The The. I listened to him a lot as a teenager. He gives a lot of advice and I cherished that. It was important advice for me.”

One nugget of wisdom in “Love Is a Lonely Thing” is emblematic of the duo’s interplay. The lyric that suggests “It will seem a fair idea / If you make it their idea” was Øye’s idea, yet it’s a trick that Glambek Bøe admits to using in the band.

“It’s funny how it describes something I often do with him, because in our relationship, Erlend tends to disagree with whatever I bring to the table. He will automatically disagree, and then I will need to let time pass, so he will forget that it was my idea – and he will start thinking it was his idea. And basically any progress that we’ve done in the field of Kings of Convenience happened through that protest phase, the oblivion phase, and then then ‘thinking that it’s your idea’ phase. So, the lines were written by Erlend but they’re very descriptive in how I see our relationship in the band.”

The musician Feist joins “Love Is a Lonely Thing” and “Catholic Country” as a third voice, yet she also served as a cheerleader. “She is our favorite singer and we respect her very much as a songwriter and artist,” Glambek Bøe says. “She didn’t actually write any of these songs, but she was in the studio telling us these songs were great. And that was very important because at that time we were starting to lose hope that there was any quality in any of these things that had been recorded during five years.”

Asked about those underlying effects in “Rocky Trail,” Glambek Bøe listens with amusement to the theories, but ultimately agrees with Øye.

“We’re a lot more dumb than that,” he says with a laugh. “A lot of times when we do something great, it’s pure accident. But we’re able to recognize the art in our mistakes. I think that’s our main quality. We are not masters of our trade, but when we do say something in a beautiful way, we are capable of recognizing, ‘Wait, that was actually pretty good!’”

There’s an element of familiarity that comes into play, too, and it stretches back into the late ‘90s, when they connected as budding musicians in Bergen, Norway, and began to write songs together. Even now, there’s a mystery about why it still works, and Glambek Bøe says he is perfectly content with that.

“I don’t know exactly what his contribution is going to do to my playing, but something happens in that meeting, and none of us are in control of it,” he says. “Being together as songwriters, we stumble upon accidents more frequently, because I will write a verse and Erlend will write a second verse and he will misinterpret what my point was. But that misinterpretation brings out another quality in the song, and then I realize that makes it so much better.”

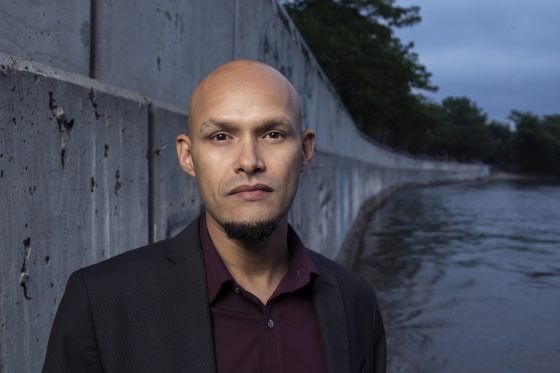

Photo Credits: Lead photo courtesy of Grandstand HQ; Inset photo by Salvo Alibrio