The Lil Smokies’ long-awaited album Tornillo reflects the vast openness of the Texas desert town in which it was recorded, possessing all of the energy that comes with a renewed creative spirit. In a phone interview with lead singer Andy Dunnigan, BGS discussed rule-bending, burnout, and how recording at Sonic Ranch in Tornillo, Texas revitalized the Montana-based band.

BGS: It sounds like this album is really special to you. Can you tell me about the process of making it? What’s memorable about this one?

AD: Yeah, this is a special one. We were coming off of two or three solid years of extensive touring. We were pretty road-worn and dare I say a little burnt out. When we came into this session we needed to become a little more unified than we had been while on the road. We were looking for somewhere that we could go and get outside of the box creatively.

Texas was somewhere we had never spent a lot of time. We wanted to go down to the desert and we wanted to be able to live on the compound. These were all [realities] that Sonic Ranch in Tornillo was able to provide us, so when we got down there we didn’t really leave for ten days.

We lived a stone’s throw away from the studio. We’d wake up and eat huevos rancheros and then head over to the studio. We were kind of autonomous in the fact that we could make our own hours. It really brought us back to life. We were really unified in our work and the production of this album, and I think that’s really ostensible throughout the songs.

How much does a new album like this, where you have brand-new material and are fresh off the experience of recording, help motivate you to keep going out on the road?

I think it’s just that we toured the last album for a couple years and got a little tired of some of those songs. We were playing so much that we didn’t have all that much time for writing. I found myself trying to juggle between writing, being on the road, solitude, hobbies, and having a girlfriend. I was thinking, “Man, there’s just not a lot of time.”

So now that we were able to hammer out some new songs, getting back out on the road seems so much more enjoyable. I think when we’re having fun on stage there’s a direct correlation to the audience. They’re feeding off us and the pillars of reciprocity are strong.

This album definitely sounds like you’re having fun and doing things your way. You sort of bend the rules of bluegrass, but always in a way that adds something to the music. How do you keep an open mind about trying new things without being gratuitous about it?

We wanted to think outside the box for this record, but we didn’t want to do it in a contrived way where we say, “OK, this is going to be a weird album, so we’ll just make it intentionally weird.” We wanted to cater to the songs and adhere to what each song needs.

On the title track, “Tornillo,” we had originally worked up our traditional way of doing it with the bluegrass ensemble, but when we started playing it, it sounded like something that should be on the soundtrack of Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary. We were thinking, “This just isn’t going to work.”

Then Rev, our guitar player, worked up a piano arrangement and brought it to us towards the latter part of the session and we were like, “Oh man, this is so awesome. We have to use this.” We were just serving the song, and that was the ethos. Once we had the piano foundation, we started experimenting with drums and horns and some baritone guitar.

It was really fun for us. We intentionally gave ourselves a surplus amount of time in the studio so we could tinker around a little bit. We wanted to experiment sonically, and I think the results are really fun. It opened our minds to what you can accomplish in the studio if you have enough time and patience.

This album has a clear overall sound. Big, open, and full of space. Is that something you went into the studio wanting to accomplish, or did it develop more on the fly?

It’s a little bit of both. We wanted to create something big from the get-go, but we weren’t sure how we were going to do that. We knew we wanted to record live because that adds a little more energy, we had it in mind to drench a lot of it in reverb to create sort of a Fleet Foxes vibe or something a little more alt. That’s the kind of music that a lot of us have been listening to and getting inspired by for the last few years. We’re all listening to a lot of different music and we wanted to expand outside of the bluegrass domain in the production at least.

In your bio it’s mentioned that you “draw on the energy of a rock band and the Laurel Canyon songwriting of the 1970s.” How did bluegrass become the avenue that you express those influences?

Well, I think we all started out playing bluegrass. I came to it in my latter years of high school. I went down to the Telluride Bluegrass Festival. I had gotten an electric guitar from my dad. He plays music for a living, so he gifted me a Strat, and then a lap steel. I listened to a lot of David Lindley and Ben Harper. Those were kind of the gateway into bluegrass music. Then when I went down to Telluride it blew my head open.

I think we all have our pioneer stories of how we got into the music. That’s how you meet the community of players. There’s this whole vocabulary attached to it but as you get older you expand your musical library. I think we listen to a lot of songwriters and a lot of rock. We still happen to play these bluegrass instruments, and we love bluegrass, but we’re just trying to express what we want to say while wielding bluegrass instruments.

Do you find that you’re an introduction to bluegrass music for a lot of your fans?

I do, and it’s one of my favorite remarks after shows. People say, “Man, I hate bluegrass, but I love you guys.” I hear that a lot and I think it’s funny and ironic, but it’s cool because I think there has to be somebody to pull you in and make you realize that you’ve been wrong about the stigma perhaps. I know I was that person at one time. I thought, “Man, bluegrass music? My dad plays the banjo. This is really lame.”

I think we’re seeing bluegrass kind of blossom into its adolescence and beyond, because for a while I think it was restricted by the staunch purists who were slapping everyone’s wrists for playing minor chords. Now we’re seeing Punch Brothers, Greensky Bluegrass, Infamous Stringdusters, and of course now Billy Strings, who all have obviously done their homework religiously and can pay homage to the traditional godfathers, but they’re also putting their spin on it. It’s really cool and it’s getting people excited. I think to be included in that group is really awesome and I think it’s an exciting time to be riding the wave.

How much do you rely on melody, texture, and other instrumental factors to further the meaning or story within a song?

A lot of it happens in the arranging as well, but a lot of times when I’m writing a song there will be a hook line, and that’s sort of from a rock standpoint. You have your verse-chorus and then there’s a riff or something. You know, this band was almost an instrumental band for a short period in the beginning. We were listening to a lot of David Grisman, Strength In Numbers, and a lot of that music.

We loved writing instrumental music, and then when I started singing and writing songs we kind of fused the two worlds together. Those little melody parts and arrangement parts are still so fun to incorporate in songs. In a tune like “Giant” on this album, we wanted something kind of spacy to create a dream-like state, so we tried to write something that sounded kind of spacey and sleepy.

Some of these songs are intentionally ambiguous in their origins. What is the intent behind that ambiguity?

I went to school at the University of Montana for creative writing and poetry and I love the way words sound together as much as I love melody. Sometimes the words and just the assonance, what they sound like, will dictate the melody and vice versa. Once I have a word in my head and I’m kind of ad-libbing on the guitar I try to steer away from some words and how they sound.

I like to write stories and have some ostensible narratives, but I also just love words and how they sound. “World’s On Fire” has a couple meanings in there but I also like to keep it intentionally ambiguous because I think it’s fun for people to create their own story.

You’ve said your time at Sonic Ranch “encapsulates all of the good things about being in a band and making music.” How did the band grow from the experience of making this album?

To circle back on what I said in the beginning, it’s a huge a sacrifice to be in a band. There’s the greatest ups and the greatest downs, kind of married to each other. Coming off of those past three years of touring we were all a little tired and burnt out, and maybe questioning if we were on the right path. During our studio session in Tornillo I think we were all realizing that this is why we do it.

When you make an album it’s like setting a bug in amber. It’s this fossilized preservation of your life at that point. The word tornillo literally means “to fasten” and refers to a screw. We named it after that place. The place really tightened us up together as friends and as a band. I remember leaving there and feeling really proud of what we had accomplished. I think it’s the most unified we’ve ever been as a band.

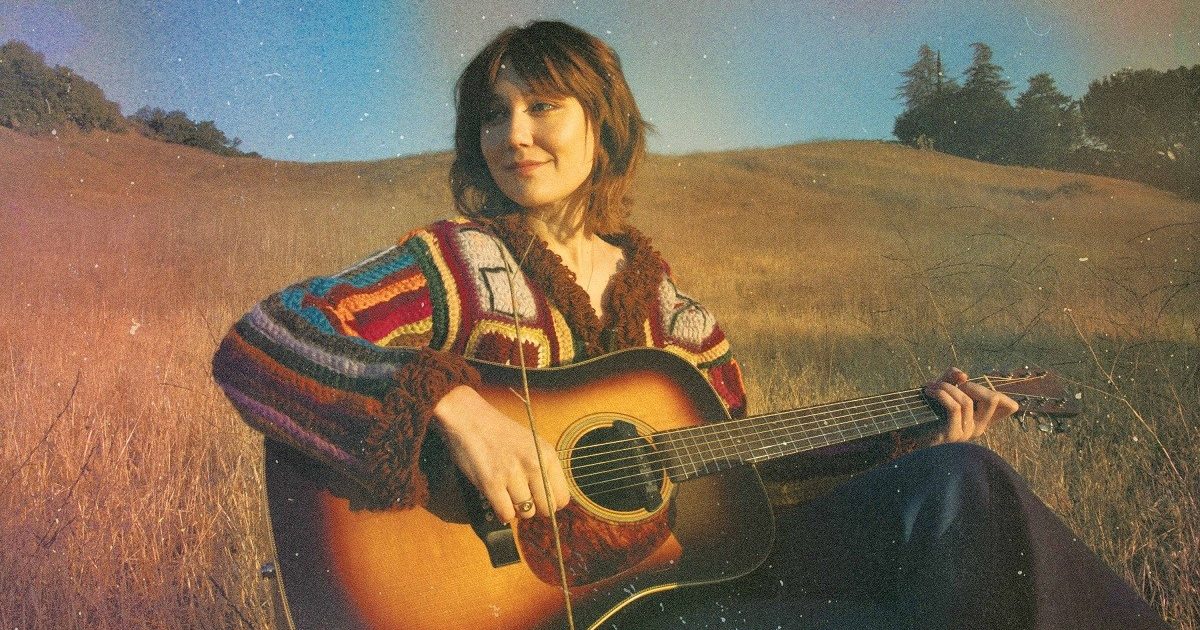

Photo credit: Bill Reynolds