Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia once said that the goal was not to be the best at what you do, but the only one who does what you do. In a way, that applies to Rhiannon Giddens’ high-profile career — except what she does is pretty much everything.

It can be more than a little dizzying to try and keep up with Giddens’ far-flung doings across multiple platforms as musician, actor, songwriter, composer, activist, musicologist and more. Her work draws from a range of classical as well as folk traditions, drawing accolades including the 2016 Steve Martin Prize for Excellence in Banjo and Bluegrass, a 2017 MacArthur Foundation “Genius Grant” fellowship and a Grammy Award for Best Folk Album for They’re Calling Me Home.

2022 found Giddens touring and collaborating with various ensembles — the classically inclind Silkroad collective, the Nashville Ballet, the Black female Americana supergroup Our Native Daughters and with multi-instrumentalist Francesco Turrisi — while the Spoleto Festival debuted her first-ever opera, Omar. Somehow she also finds time to do the Aria Code podcast for the Metropolitan Opera, too.

Whew.

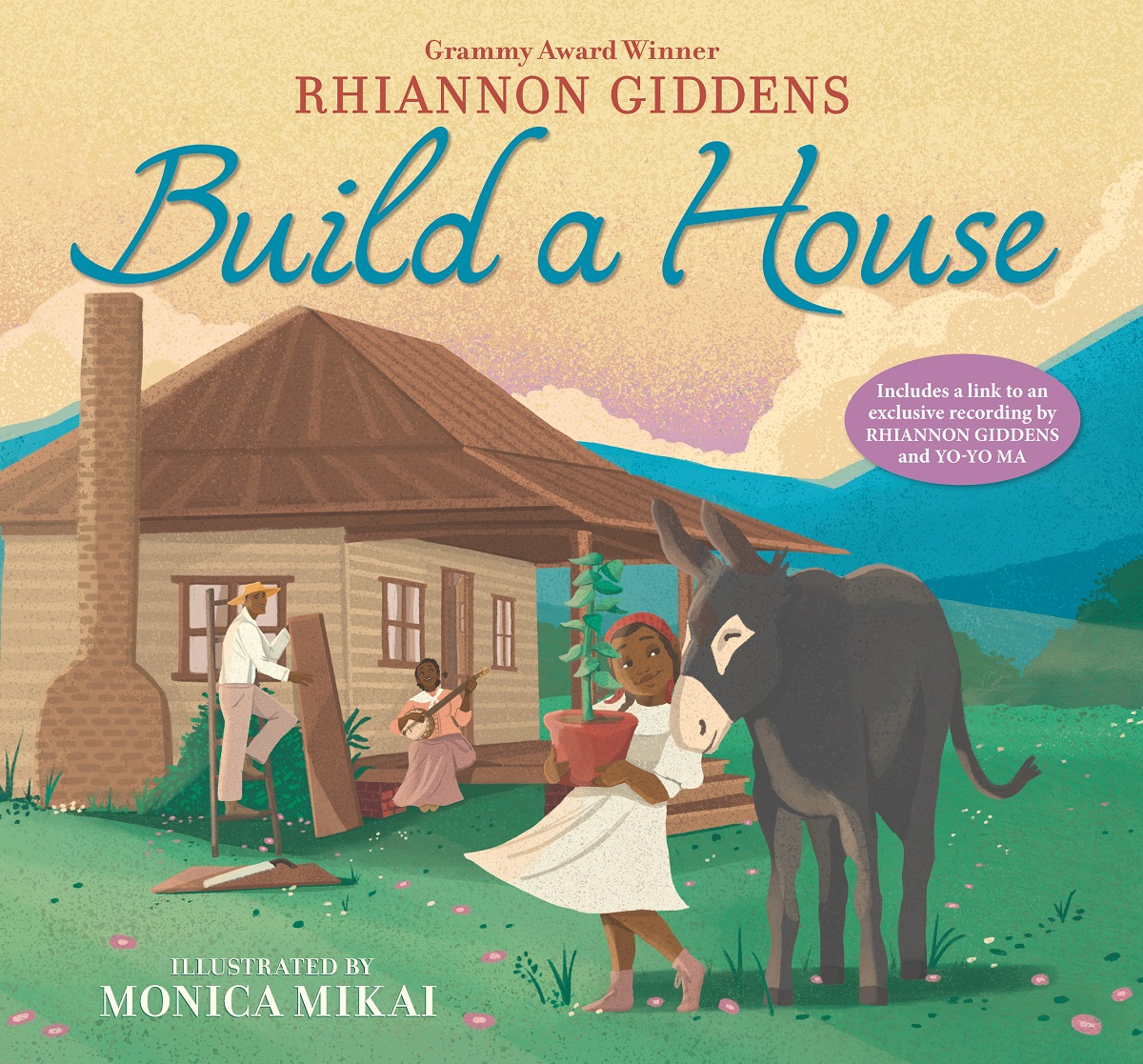

As for future endeavors, Giddens has multiple projects percolating, including hosting the 2023 PBS series My Music with Rhiannon Giddens. In the meantime, she hits bookshelves for the first time this fall with Build a House, the first of her four children’s books to be published by Candlewick Press.

BGS: Thanks for taking the time. Where are you calling from?

Giddens: Ireland. I’m mostly here when I’m not on the road because it’s where the kids are. It’s hard. I have them half the year, so I have to fit a year’s worth of work into the other half because the bills don’t just pay themselves. It would be different and easier if I were still with their dad, but we’re not together anymore and I’m on my own when I’m with them. So I’m a single mom, working full-time to cram all the work into as little time as I can. It’s difficult not to feel pulled in a lot of different directions, while constantly feeling jet-lagged.

I haven’t been able to have much of a balance, to be honest. I’m doing everything I can to fit three lives into one and something’s got to give because I don’t want it to affect my kids. I’ve said it many times, but I just have to start making space on my calendar. In my working life, a bunch of projects got pushed into this year because of the pandemic, which has been insane. I am fortunate to have a lot of work, because a lot of people don’t. But it’s sometimes hard to enjoy what’s happening.

Your first children’s book is coming out, Build a House, illustrated by Monica Mikai. How did that start out?

It began as lyrics, and that one was kind of always a song. Sometimes I write poems that turn into songs, but this one was always lyrics. It goes back to the pandemic, when Ireland had a hard lockdown. That was going on when the protests over George Floyd started in 2020, which was super-frustrating to watch. I was over here feeling useless and sitting at my kitchen table thinking, “Forget Covid, I’d be on the front lines in the States right now.” I was trying to explain to my children why I was crying at odd times.

At times like that, I often write about it. “Cry No More,” that one was after the Charleston church massacre. Emotions will pour out: “What the hell do you people want? You brought us over here to build your frickin’ country, now what?” That became, “You brought me here to build your house,” and it went from there. Yo-Yo Ma reached out to ask if I wanted to do something for Juneteenth, and this song was perfect for that. So I recorded and filmed my part and we put it out on Juneteenth 2020 to an amazing response. That made me feel a little better.

At what point did it go from song to book?

It was actually on Twitter, where somebody said, “Hey, this should be a kids book!” And that got me thinking, huh, yeah, cool idea. I’ve been wanting to write a book about American music history, and my book agent Laura Nolan has been patiently waiting, checking in periodically. So I asked her, “What do you think about a kids book? Here’s an idea.” We set up meetings, Candlewick Press came in with an amazing offer for four books, and this is the first. We struck a deal and they sent us a short list of illustrators — all women of color, I did not even have to ask — and I picked Monica, which was pretty much the beginning and end of it. I’ve never spoken to Monica, which is how it works with kids books. Authors and illustrators communicate through the editor without getting together, each doing their thing. Next thing I knew, I was sent a sketch of the story she got out of the song, which was amazing. I was totally blown away and might have cried a little bit. When I saw her finished work, I could not have imagined it better than this.

That seems so odd, that writers and illustrators work completely separately on kids’ books.

I actually like that it’s separate. She’s an artist and I’m an artist, too, and these are two different forms coming together. She brought her art to bear on my words, so I feel like I did what I’m supposed to do. She got it without having to talk to me, which is the point of the book. It was an amazing experience, and not so different from when I bring another musician into the band and tell them, “Do what you feel like doing, and I’ll tell you if it jibes with what I’m doing.” But I never start with saying, “Do this” – unless it’s telling a bass player, “Don’t do 2-5-1 bluegrass bass-playing in anything I do.” I hire them to bring their expertise, working with them to do their thing.

The next book will be We Could Fly, out next year, based on a song I did with Dirk Powell and illustrated by Briana Mukodiri Uchendu. And the rough draft of the third one is done, about Joe’s First Fiddle — riffing on my mentor Joe Thompson. The fourth one will be about the banjo. But I’m really excited about paying tribute to Joe this way because I’ve wanted to write this since he was alive and would tell the story about his first fiddle. What I wrote is not exactly the same as the story he’d tell, but I sent the rough draft to Justin Robinson [her fellow Carolina Chocolate Drops alumnus], and he gave it a thumbs-up.

Tell us more about the book about American music history.

It’s American music through my lens, based on all the speeches and keynotes and lectures I’ve given over the last few years. Mostly it’s about the myths of American music, like the idea of where the banjo came from. That’s the most obvious myth, that it was born in Appalachia and invented by Scotch-Irish immigrants. No they didn’t, even though they played it. The banjo came from Africa. So what are the myths, and whose intentions do they serve? It’s the idea of looking at the culture we have in America through music, the misunderstandings we have and how that hurts us as Americans by obscuring a true understanding of who we are as a country. Basically, I’m talking shit all the time, and I want to put it in book form.

You were just in Tryon, North Carolina, filming for My Music with Rhiannon Giddens at the birthplace of Nina Simone. What can we expect from your show?

It’s me taking over David Holt’s State of Music, starting next year. That filming was really special. I had not been to the Nina Simone house before and it was cool even though I’m not a thing-and-place person, you know what I mean? Maybe I’m just too cerebral in an emotional-deficit way because it seems like those experiences don’t affect me so much. But I love seeing how they affect other people. It was really joyful to see Adia (Victoria) in that space, how she was affected by it with prickles all over her back, and my sister was blown away when she visited. For me, what’s important about Nina Simone is captured in her songs and performances. The rest, I’m not sure standing in her childhood house does anything for me. I live so much in the ether, the material aspects of life don’t hit as hard for me. But that’s okay, and others feel differently.

After studying opera in college and then going on to folk music, you performed on an operatic stage for the first time in almost two decades this year – Porgy & Bess in your hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina. What’s it been like to return to opera after so long?

It had been 18 years and it’s been really interesting to log back into that and realize how much I had missed it. I loved the Chocolate Drops and everything I’ve done since then, but a lot of it was more of a calling than pure joy because of the work I do. There have been a lot of transcendental moments on stage, but I realized I’d been missing a lot. Like standing on stage and just singing, no mic, just you and the orchestra and other singers. A beautiful thing. It was nice to come back to that as a performer, writer and composer.

As an art form, opera has such power. It gets a bum rap, the way it’s been taken over by the elite as a way to differentiate. They go not because they enjoy it but because it’s what they’re supposed to do at a certain level. It’s been great to get back into the art form, engage with it as itself without expectations as a young singer or having to deal with all the European dead white guys. I’ve come into it with a totally different perspective, with this grounding I had years ago.

With everything you’ve got going on, it must be hard to find time for your biggest project of all, composing a Hamilton-esque historical musical about the 1898 massacre in Wilmington, North Carolina. What’s the status of that?

I’m in constant contact with my collaborator, John Jeremiah Sullivan, who is a slow burner himself. The New Yorker interview profile he did on me took five or six years – I went through three different managers! But he takes time because he is extraordinarily thorough, and he keeps finding important things. I keep wanting to be in that space with him, getting together and creating. I think we are close to getting the institutional support we need. I don’t like to force things. Whatever is ready to go, I try to create a space for it and so far things have worked out in a beautiful way. Another project just came onto the burner and it might get going before Wilmington, or it might not. It depends on timing and co-creators, where they are and what they’re doing. But this is an important story and we’re gonna do it.

Photo Credit: Ebru Yildiz