In 1981, a guru from India named Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh purchased hundreds of thousands of acres just outside the small town of Antelope, Oregon. In the middle of nowhere, he and his followers—called Rajneeshees, who were either practicing a religion or succumbing to a cult, depending on who you ask—planned to build their own utopia, a place where they could practice their faith in privacy and community, far from the outside world.

But not quite far enough.

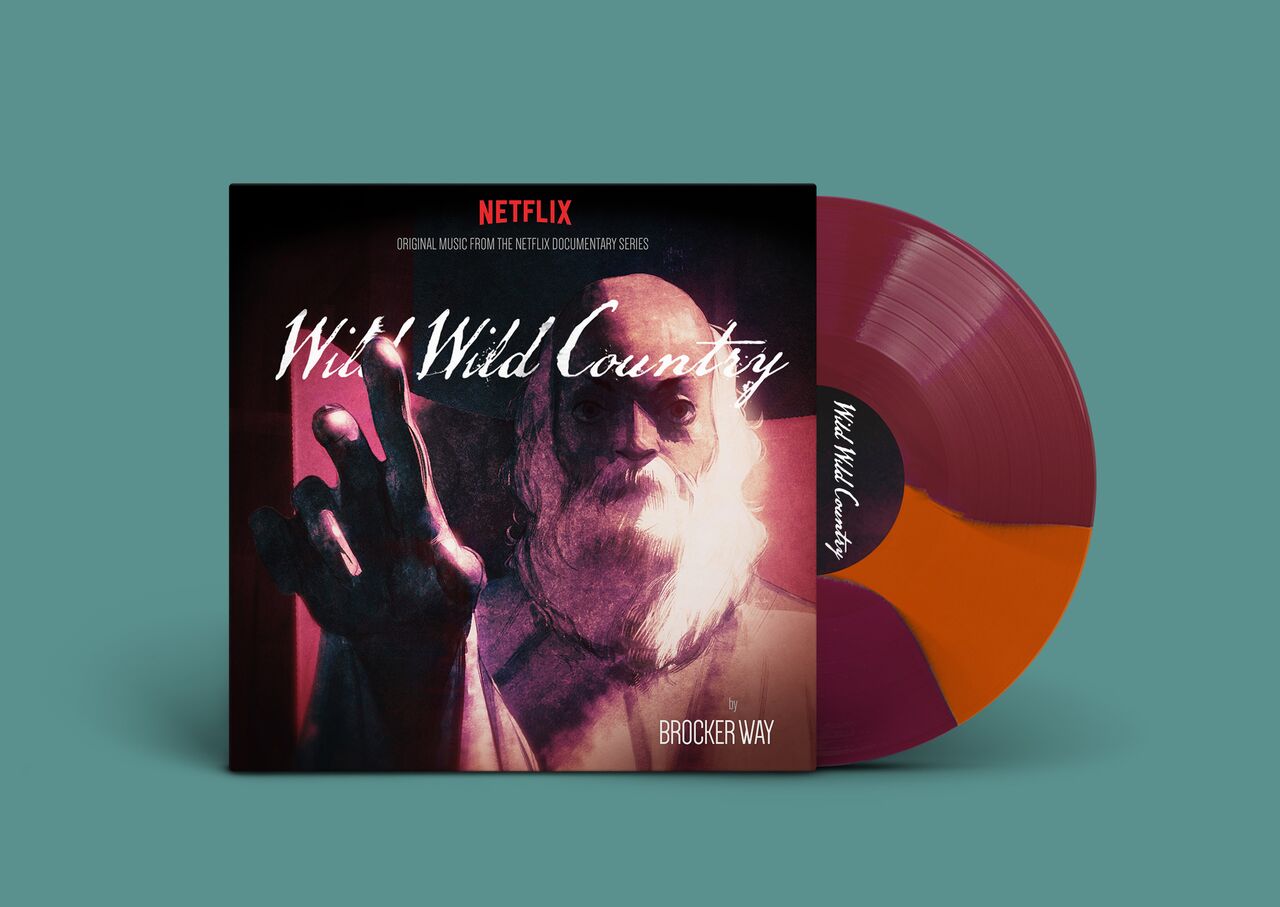

The story of how the Rajneeshees clashed first with the locals in Antelope and then with state and federal authorities forms the arc of Netflix’s six-episode documentary Wild Wild Country, one of the biggest binge-watch events of the year. It involves mass poisonings and bizarre murder plots, daring escapes and government espionage, betrayal and treachery. In other words, this is a very American story, one that takes distinctly American music.

If it’s the job of the directors to make sense of so many competing stories—those of the Rajneeshees and the Oregon locals—then it’s the job of the film composer to bring humanity to all of the various perspectives, to ensure viewers see everyone onscreen as a human being. That task fell to Brocker Way (pictured below), who drew from the vernacular style of Aaron Copland as well as from the avant-garde minimalism of Terry Riley. He worked closely with the documentarians Maclain and Chapman Way, who happen to be his brothers. He knows them as Mac and Chap.

The nephews of actor Kurt Russell, the brothers started their film education early. “Our father was a screenwriter for a long time,” says Brocker Way, “and he would have these movie nights for us on weekends. Even out of college, you’d go visit Dad and he’d have set aside all these movies for you to watch. He curated for us what we now realize was an amazing series of films.”

Scores were as crucial that education as the films themselves were. “If I’m in the car with my dad, he’s playing John Barry’s score to Out of Africa, and those things just seep into your subconscious. You can only watch Lawrence of Arabiaso many times before you start finding minor chord progressions in your own scores. We all have our music journeys, and we all have our film music journeys.”

The brothers first worked together on the 2014 documentary The Battered Bastards of Baseball, a feature-length documentary about Oregon’s independent baseball team the Portland Mavericks. But Wild Wild Countryis six episodes, each lasting about an hour. That’s roughly three feature-length films. Brocker Way composed a lot of music, and he composed it all quickly, tying together various styles and palettes and themes and variations and working almost as fast as his brothers were editing the film. He explained the process to The Bluegrass Situation.

When you and your brothers are working on a project, at what point do you get involved?

I’m somewhat involved from the very beginning, because I’m their brother. From the time they started on it, from the time they got the first clips in—the first footage from the Oregon Historical Society—I knew about the project and what they were doing. In the very beginning they will put some of the footage together with background music, and I see all of that and we have lots of discussions. Lots and lots of discussions. They want me to understand the story completely, and we’d talk about the characters, talk about what we’re trying to achieve. But that’s not really me working full-time on a score. They’re working full-time: editing, researching, interviewing. I just get to hang out and talk to them about those things.

I’d say maybe about four or five months before our final deadline is when I’m scoring full-time around the clock. On Wild Wild Country they were moving into their fourth episode—I think they were halfway through their fourth episode—when we just went after the score full-time. They’d send me the edits, and I would score at a pace that eventually catches up to their edit, and then we score and edit in tandem. I’ll just score and hand them in stuff by the morning, and they’ll be editing to it and whatnot. That’s the process.

It’s almost like you’re writing in real time.

Yeah, it’s a lot of fast work. Chap and I, before he got into documentary films, we made music together, and my experience with pop music was: You find some inspiration, you work on a song, you have time to wait until your piece is ready. Scoring film is a different process. It starts off with a band and then you’re off. You work with a team and you have consistent deadlines. In some cases it’s tough, but in other ways it’s also fun and liberating. You’re forced to move on. You can’t be a perfectionist. It’s a fast, intense process for those few months.

It feels like it’s such sensitive work. You’ve got to draw out very subtle things in the film and in these interviews, without overstating anything or crowding out the person on screen.

The approach Chap and Mac take with music in their documentary is that they want the music to really support the world that the characters are bringing or that they see. They want to bring the audience down to the level of the talking head and to follow the talking head on their journey. So our music is out front. There is a lot of negotiating and figuring out how to not step on the character. But we’re okay with music pushing the narrative a little bit.

I’ve been asked a few times: Is the music leading us too much? Or is the music going back and forth so that it’s meant to show a moral ambiguity? For Wild Wild Country, we didn’t want to take a side. We wanted to push you along multiple journeys and see what kind of effect that has on you as a viewer.

There are these constantly shifting sympathies in the series. At first you’re not sure what to make of the residents, and then you’re not sure what to make of the Rajneeshees. You’re being asked to identify and sympathize with both sides, and the music plays into that.

Some people have criticized that approach, but some people have also complimented it. Chap and Mac don’t really like the approach to documentary where the viewer gets to feel above and better than the talking heads. Music can really throw you down to their level and accept their journey for a little bit longer. That’s kind of theoretical, but it has a practical effect.

If you’re watching the edit back and there’s no music, it’s amazing how silly almost everyone comes across on camera. Like, everybody. Even really intelligent, brilliant people come across as silly, because being interviewed is not a normal situation in life. So the viewer can become slightly judgmental. Part of the role of the music is to bring humanity and life to the characters, so that viewers are willing to engage with them. On that level, I’m not saying, How am I going to score the trauma of this situation? It’s more along the lines of, How do we score this person’s world?

Is that a reaction to what I see as a trend in activist documentaries, like Michael Moore or Dinesh D’Souza, where they’re trying to manipulate you to feel a certain way?

I would say we are manipulating the viewer to do something, but what we’re trying to manipulate the viewer to do is very different. We want you to remove your arrogance as a viewer. We’re not letting you know how we feel about these characters or what we want you to think. Two reasons. One, we all had slight disagreements about these characters and their journeys. Almost everyone does. We didn’t have any creative disagreements, though, about how we wanted to score it.

The second reason is that Chap and Mac are hoping that when you finish the series—you might have binged it or whatever—that you come away feeling something like exhaustion from the journey. Maybe you don’t know if any of your opinions have changed, but you feel slightly different. I think that’s why we’re so attracted to documentary films, that kind of activism. By tearing down our arrogance and forcing us to follow these characters, we learn a little more about ourselves than we knew going in.

How do you devise a sonic palette to fit that approach?

At first we thought we were going to stick to a very specific palette, but the moment you start trying to give different perspectives, not only does the tone shift, but the palette shifts as well. So in the beginning, the palette is focused, but as the project goes on, you start bringing in different arrangement styles so that you can have a breath of fresh air and shift perspective with the characters. Sometimes it’s almost just narrative techniques: We’re opening on a new scene, a new setting, a new world, so we’re going to get a new tone and shift instrumentation or style. And we build on that through the episodes.

In this case there were two different approaches. One involved classic American scoring and songwriting. The songs we were going through had this kind of cosmic cowboy feel to them, like the ghosts of legends past looking over this land and singing a song of battles that had taken place. In the beginning we had Aaron Copland and Charles Ives and Ennio Morricone. Those felt almost like some sort of American ideal—well, Morricone is Italian, but he scored all these Westerns.

But when you start scoring them, and as the sections change and the motivations change, certain things might still work but for very different reasons. We were doing the section when all the homeless—they called them street people—start to flood into Rajneeshpuram, and we had this noble, simple chord progression playing, just strings and brass I think. But we had these polytonal ideas in the background. At that point the Charles Ives thing offered something completely different than what it had originally given us. There was this slight foreboding: Something’s off here, and as a viewer you’re unsure how to feel about it.

In this context someone like Ives or Copland plays like a kind of roots music. Some of them were drawing on older American music.

When you have all these different threads and different styles, you have different opportunities to explore, but everything always connects to everything else in some ghostly way. We were also looking at Terry Riley and Steve Reich in the beginning, and there ended up being a ton of Terry Reilly’s influence on this score, especially with Swami Prem Niren. It’s a completely different style of American composer [than Ives or Copeland], coming from a completely different angle, and it ended up working out so well for us. It all feels so American, and in the end there’s a ghostly tie between it all, some sort of battle between these styles themselves, just as there’s a battle between these different people.

I would think that would help a score stand apart from its visual component. Even on vinyl it tells a story that way.

I feel unbelievably blessed that I’ve had this opportunity not just to do the score, but to have the soundtrack released on its own. I’m most lucky that Chap and Mac’s style of documentary filmmaking doesn’t just want music. They want music that makes itself known. They want the viewer to hear the music, because they think you should know that there’s some manipulation there and just be along for the ride. What happens at the end of that is you have music that plays as a normal composition. When you’re working, you know you need to make music that is upfront, that people will recognize. You know you’re going to be using chamber ensembles, and you know they want to hear the rub of the strings. They want to hear that solo horn come out. That allows us to have a group of tracks or cues that stand up on their own.