A spry country tune driven by Chris Hillman’s hyperactive mandolin and Sneaky Pete Kleinow’s spacy guitar solo, the Flying Burrito Brothers’ “My Uncle” is not a song about family. The uncle they’re harmonizing about is Uncle Sam, who in the late 1960s wanted members of the band to kill others and possibly be killed in Vietnam. Gram Parsons had already secured a somewhat dubious 4-F deferment, making him ineligible for military services for health reasons, but the Army continued its pursuit. “So I’m heading for the nearest foreign border,” Parsons sings, resigning himself to the ignoble fate of a draft dodger.

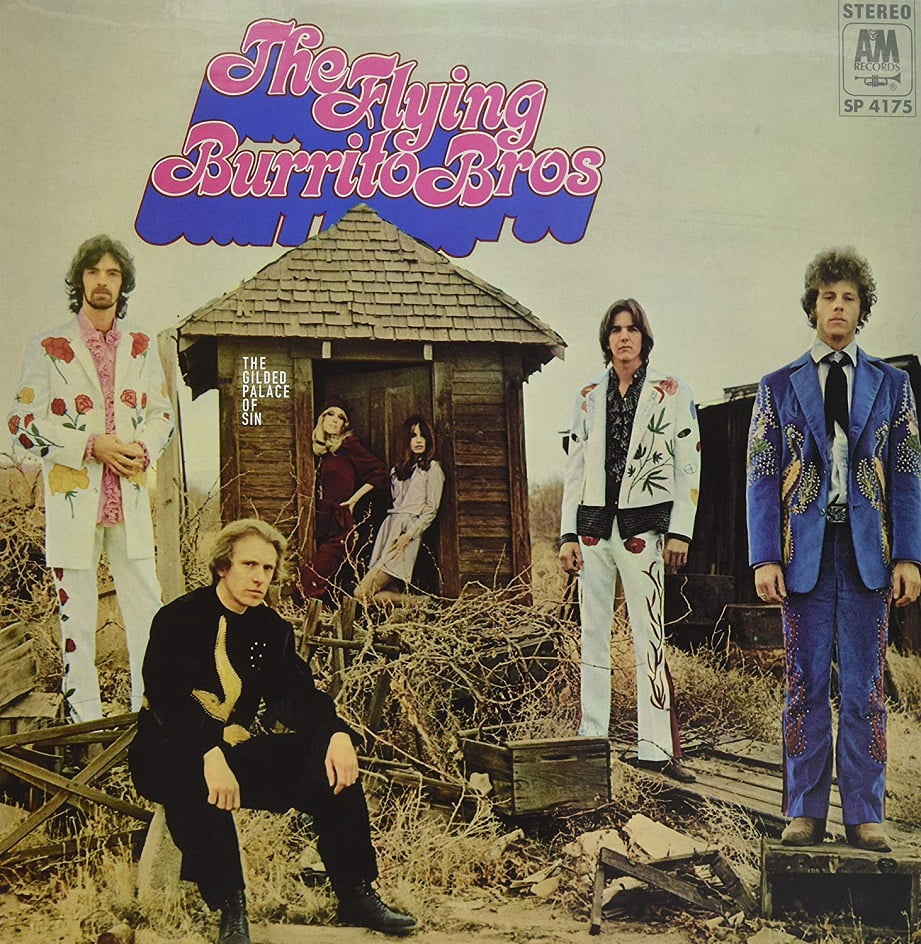

In the late 1960s, rock and roll was rife with anti-war songs. Some were angry, like Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son.” Others were riddled with mortal dread, like “Feel Like I’m Fixin’ to Die Rag” by Country Joe & the Fish. But few sounded anything like “My Uncle,” an album cut from The Gilded Palace of Sin. For one thing, as the Flying Burrito Brothers ponder what they owe their country, they sound more melancholy than outraged, as though they’re singing a breakup song with America.

For another thing, they dressed their anti-war sentiments up in the threads of country music, which was already viewed as both musically and politically conservative: a counter to the counterculture, representing the moral/silent majority that finally put Nixon in the White House in 1968. “Okie From Muskogee” was the defining country hit of the era, a song that tsk-tsks the hippies, roustabouts, and even the conscientious objectors burning their draft cards. Merle Haggard may have written it to gently puncture the sanctimonies of an older generation, but listeners heard no irony or distance in lyrics about wearing boots instead of sandals and respecting the college dean.

Given the canonization of Parsons over the last few decades, as well as the gradual breakdown of genres and styles over time, it’s easy to forget just how contrarian it would have been for a West Coast rock band to embrace country and bluegrass. The Flying Burrito Brothers had risen from the ashes of the Byrds, a group which earlier in the decade had included Gram Parsons for just one album, Sweetheart of the Rodeo. A relative flop upon release, it nevertheless invented country rock with a set of twangy originals and covers of songs by Cindy Walker, Haggard, and the Louvin Brothers. Aside from Dylan, who was covered by everybody in the late 60s, these weren’t especially hip influences at the time.

Draft dodging may have been anathema to country music, but “My Uncle” is at its heart about more than just protest. “A sad old soldier once told me a story about a battlefield that he was on,” Parsons and Hillman harmonize. “He said a man should never fight for glory, he must know what is right and what is wrong.” The Flying Burrito Brothers plumb that stark moral divide on “My Uncle” and every other song on their debut, parsing temptation from salvation, wickedness from righteousness, and painting a picture of an America where you might easily confuse one for the other. Country music becomes the ideal vehicle to explore ideas about violence, consumerism, free love, and more broadly, the notion of sin.

The idea of sin illuminates every song on The Gilded Palace of Sin. The rollicking “Christine’s Theme” opens the album with a woman bearing false witness: “She’s a devil in disguise, she’s telling dirty lies.” “Juanita” imagines an angel rescuing the band from booze and pills. “Hot Burrito #2” invokes Jesus Christ by name — not cussin’ but praying. “Do Right Woman,” a Dan Penn/Chips Moman number popularized by Aretha Franklin, is transformed from a lover’s plea into a preacher’s wagging finger. “Dark End of the Street,” by the same Memphis songwriting duo, is about coveting your neighbor’s wife: “It’s a sin and we know that we’re wrong.” When the Flying Brothers get to the bridge, “They’re gonna find us,” they might as well be talking about angels and demons.

“Sin City,” the album’s centerpiece, is the band’s version of Jonathan Edwards’ “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” which mixes Biblical imagery with twangy country harmonies to create a startlingly dire depiction of Los Angeles as both Sodom and Gomorrah. It’s a place where avarice rules all, leaving even the determined and upright struggling for footing. “That ol’ earthquake’s gonna leave me in the poorhouse,” the Brothers sing, echoing Edwards’ assertion that all humans as sinners are “exposed to sudden unexpected destruction.” Wealth won’t buy redemption or avert damnation: “On the thirty-first floor, that gold-plated door won’t keep out the Lord’s burning rain.” (That’s likely a sly reference to Larry Spector, the Byrds’ former manager, who lived on the thirty-first floor of a luxury LA high-rise).

Jesus shows up for a verse of “Sin City,” and he may or may not reappear in the close “Hippie Boy,” a spoken-word homily in the style of Hank Williams’ moralizing alter ego Luke the Drifter. Hillman tells the story of a boy caught up in the violence between the right and the left. In his 33 1/3 book on Gilded Palace of Sin, Bob Proehl suggests the band might have been inspired by the riots at the Democratic National Convention the year before. “The so-called riots in Chicago were actually more of a police action,” he writes, “a beatdown instigated by the gestapo tactics of Mayor Daley’s police force right in front of the delegates’ hotels.” Even before the song concludes with a rousing chorus of the old hymn “Peace in the Valley,” the song is a damning attack on anyone who would employ violence in the name of morality.

While they are using country music to interrogate the genre’s own high moral standards, the Flying Burrito Brothers don’t come across as scolds. Instead, they’re doing something more ambitious yet far more personal: They’re trying to find their own way in this sinful America, trying to find the moral high ground in shifting sands. On “My Uncle” they sing about dodging the draft with guilt and sadness, but they understand it is a moral predicament. “Heading for the nearest foreign border” is preferable to enlisting and killing. That makes The Gilded Palace of Sin unsettlingly prophetic fifty years after its release, maybe even inspiring in its spirit of dissent and moral defiance.

None of the Brothers would ever sound quite so political or quite so driven by moral inquisition on subsequent albums. Their follow-up, 1970’s Burrito Deluxe, sounds good but has little of the brimstone determination of their debut. Parsons left the group shortly after its release, and his pair of solo albums drive the roads of a murky, mythological America.

However, less than a year after the release of The Gilded Palace of Sin, the Brothers witnessed Biblical calamity firsthand when they played the Altamont Free Concert. Billed as a West Coast alternative to Woodstock, it included San Francisco bands Santana and the Jefferson Airplane, with the Rolling Stones headlining. The crowd of 300,000 was already agitated when the Brothers played their early set, and by the time the Stones took the stage, they were volatile, and hostile. During a performance of “Under My Thumb,” one of the Hell’s Angels working security stabbed and killed a black man named Meredith Hunter, stopping the show and casting a pallor over the event, if not the entire decade. It was intended as a show of countercultural unity, but it must have seemed like God smiting the hippie generation: the end of the 6os in great and gory conflagration.