Adeem the Artist is not afraid to confront the complex realities that some country songwriters would find more convenient to gloss over. A nonbinary musician who lives in Knoxville, Tennessee, with their wife and young child, Adeem is nothing if not honest. Throughout their new album, White Trash Revelry, they have written songs that feel so deeply personal, yet relatable, exposing pain and struggle in nuanced ways that can make a listener reflect in one moment and laugh in the next.

If you won’t take our word for it, perhaps Brandi Carlile’s will hold more weight: “Adeem the Artist is absolutely incredible. One of the best writers in roots music that I’ve ever heard,” she noted on her SiriusXM radio show, Somewhere Over the Radio. On the last night of a tour supporting William Elliot Whitmore at Off Broadway in St. Louis, Adeem captivated the audience, weaving stories and playful banter between original songs. BGS caught up with them before the performance, and they were generously on-brand with their openness and honesty.

BGS: I read the essay you wrote in the liner notes. From that, and listening to the album, I was struck by the range of emotions with which you reflect on childhood. Can you tell me a little bit about the process of writing these songs and reconciling those mixed emotions?

Adeem: The suffering and celebration thing is important to me. There’s a (Kahlil) Gibran line where he says, ‘the deeper that sorrow carves into your being, the more joy you’re capable of holding.’ That’s something that I’m connected with on this record. They’re not two different things. They’re intrinsically bound.

I mean, this was a frustrating thing for my parents when I was a teenager and a young adult. I was still very plugged into the Christian Church, really passionate about Jesus, and about, you know, building the kingdom of God, and telling ’em they were hypocrites for having a large television and living in a big house and saying like, “You have to give away your money. If you wanna do this, this is what it looks like.” That’s the Christianity that I grew up with. It had a lot of toxic impacts on me, but it is also the reason why I’m who I am. It’s the reason why I care about justice. It’s the reason why I care about equity. It’s the reason why I care about racial equity in country music. The biggest thing for me is to really try to be honest about the experience that I had growing up as a low-income white kid in the rural south.

Tell me a little bit about your songwriting process.

My songwriting process is not exactly rote. I have extensive rules for songwriting, but most of them are kind of unspoken and latent and implicit. I do find the idea that you have to write every day to be a bit obtuse. I think it misses the mark of how much of the experience of writing is sort of adding to your palette. I feel like I’m always working on songs. I just gestate a lot. Louis Hyde talks about the parable of the shoemaker and how you can work and work and work and toil and toil and toil, but sometimes the lightning strikes at night and you wake up and it’s there, it’s done. Your unconscious kind of fulfills the duty of the imagination. I think that’s true. I think about moments that we don’t want to talk about, that we don’t want to address, that we would rather paint over.

I was thinking about the idea of trying to reconcile things as an adult that you learned from your loved ones.

Yeah. I mean, I love Thanksgiving. I like cooking a lot and I like cooking for my friends and the people that I consider family. It’s special to me, and I’ve always loved the Thanksgiving story. You know, my ancestors came over on this big, beautiful boat, and they got here and there were these amazing, interesting indigenous people, and they shared their food with them, and they shared their food back, and then some of them even fell in love and they had this big dinner. It’s beautiful. I think anyone would think it’s beautiful, but it’s just not true. It never happened. The reality is we tried to exterminate them. My ancestors came here and did everything they could to make sure there was no trace of them on the earth, and they survived. Now that’s a special story, but it doesn’t frame my ancestors in the best light.

And I think that what’s important to me is that I figured out that it doesn’t do anyone any good because it assuages us of the responsibility to make things right. That’s the same thing that’s happening with a lot of areas in country music where people are able to rewrite these sort of Thanksgiving stories. What I found was that I would rather tell a story that is still beautiful, that’s still wholesome, that’s not trying to demonize anybody, but is trying to welcome a sort of healing to try and fix the broken pieces. A lot of country musicians make the choice to tell a lie because they think it’s making things better in some way, and it’s a lie and it’s hurting people in very real ways. I don’t think that telling the truth means I have to sacrifice any compassion or kindness or love for my community or my culture, or my family, my ancestors, my people, nothing. It’s just holding it all.

I want to ask about a song from your last record, Cast Iron Pansexual, in which you address Toby Keith with references to three of his songs, by my count. From “I Wish You Would’ve Been a Cowboy,” it sounds like you were at least somewhat of a fan of Toby Keith. Talk about what it was like to grow up singing along to those songs and then having a sort of epiphany about the lyrics as you got older.

Sure. I mean, for one, I don’t know that I stopped regarding Toby Keith as an excellent songwriter. It’s tough for me to answer that because I went through a really significant change. I grew up in Charlotte. My family’s from the lower Piedmont region, just outside of the city. When I was 12 or 13 years old, we moved to Syracuse, New York. I had been listening to country music but also growing apart from it pretty naturally. I was what some might call “fagish.” I was a bit effeminate. My mom smoked weed and went to metal shows. I got in trouble for swearing in class one time. I didn’t fit in the rural town where I was.

Just all that to say, I felt estranged from it probably before I started interfacing with any of the heaviness of why I was feeling estranged. When I moved to New York it was like, you know, it doesn’t matter what you wear when your accent’s like, (says in a thick southern accent) “Oh, me mama gonna go get the buggy from the grocery.” You know? It’s like I was a good old boy all of a sudden. I was a redneck, which is a really weird thing to interface with. So, country music was something that I shied away from and didn’t think about for a long time.

But as those years went on, [the experiences in New York] became further and further from me. You know, I think about it now, and it’s like, man, I was listening to Garth Brooks sing about how being gay is okay in the ‘90s. Holy shit. You know what I mean? The country music industry became so richly conservative in ways that it wasn’t before, even in the aftermath of 9/11 and with what they did to Natalie Maines, you know? Talk about cancel culture…

Luckily there are many artists out there who have bucked the trend, but there’s certainly a lot of country music that perpetuates misogyny, American exceptionalism, and exalt “the South” in such a way…ideas that you decry in your songs. You touched on it already, but can you talk more about your relationship with country music in general?

There are two things I want to say. The first is a merging of this question, and the last one you asked me, which is, I do want to say I really toiled over whether or not I wanted to release this song (“I Wish You Would’ve Been a Cowboy”). I have jokingly said in the past that it’s because I didn’t want Willie Nelson to be disappointed in me. But the truth is, I don’t know Toby Keith. I don’t know what he’s about. I don’t know how he feels about this. I don’t know if he’s ever thought about it. But most people, when they’re told, “Hey, something you did hurt people,” they’re like, “Well, fuck, I didn’t mean to do that.” I would imagine that he would probably have the same reaction. So, I really hope to have that sort of interaction. I’m not a cancel culture person. I really would like to see people healed in some meaningful way.

My relationship with country music has been estranged until about, I’d say, six or seven years ago. I discovered Roger Alan Wade. He wrote the Jackass theme song, “If You’re Gonna Be Dumb, You Gotta Be Tough,” and “Butt Ugly Slut,” and some other disgusting songs. But he’s written some really stunning poetry. He’s got this song where he describes the West Texas sunset as “spread out like rusted chrome.” It’s really gorgeous. He has such a poetic lens and such a compassionate view at fundamentally broken and lost characters that drew me in. The Mountain Goats are one of my favorite bands, and he seemed to be writing about some of the same riffraff that would cycle a Mountain Goats album.

And through him I got into Guy Clark and John Prine and James McMurtry. John Prine was, in many ways, like coming home. I’d always been really into the marriage of suffering and celebration. That was always kind of like my bag. I think I’m better at it now than I used to be. My mark has been a sort of conglomerate of intense emotional pain interspersed with moments of just chaotic jack-assery and laughter, you know? When I first heard John Prine, it was like a true north. I heard him and I was like, “Oh, he is following something that I’m following. And he’s closer to it.” I felt such a natural kinship with him. And I felt that with a lot of other country musicians too.

On White Trash Revelry, it seemed like you embraced more of a pop-country sound, whereas the prior album felt a lot more folky and subdued. Did that happen organically or was that something you were trying to accomplish in the writing and recording process?

Yeah. I was trying to write some songs. There was a period where I was really into the idea that I might get a publishing deal someday, and I love my family a lot. The idea that I could be able to afford to give my family a good life and not have to be on the road or whatever was like, “Yeah, I would like to do that.” So, I wrote “Baptized in Well Spirits” and “Middle of a Heart.” There are probably four songs on this record that were written pretty strongly…like they were crafted, you know? The intention, when I wrote them, I wanted somebody else to sing them. But then, as this album started taking shape, it became clear they really fit in. So, I don’t know if that’s the direction that I will persist in moving forward or not, you know, incorporating the pop country elements of it. But I like having it on my palette, and I’m not gonna take it off. If it feels right, I’ll keep doing it.

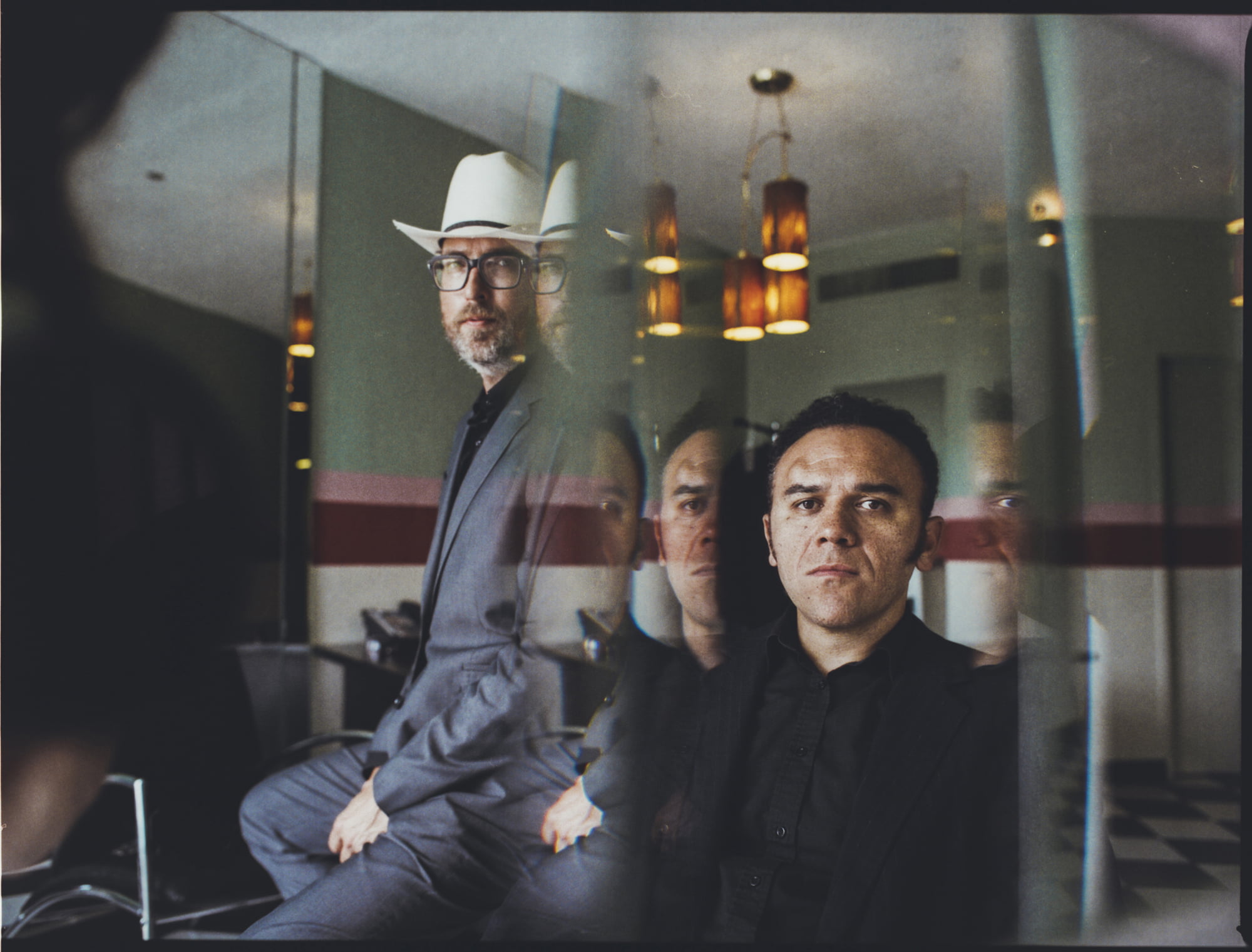

Photo Credit: Shawn Poynter Photography (Top Image)