Slowly stepping off a small stage underneath a large tent at the Suwannee Spring Reunion, Peter Rowan wipes the sweat from his face with a fresh towel and releases a big sigh — another whirlwind solo set in the books, another audience clapping wildly for the mesmerizing, singular presence that is Rowan.

It’s hot out, especially for mid-March, with the oppressive heat of an impending southern summer already present in the depths of rural Florida where the gathering calls home. Dozens of concertgoers rush over to Rowan to get an autograph and take a photo together, but more so to share a story or memory of another juncture where their paths crossed.

At 80 years old, Peter Rowan is an American musical institution, this cosmic chameleon of raw talent and endless curiosity, one who has meandered up and down the peaks and valleys of the universal sonic landscape — bluegrass, rock ‘n’ roll, reggae, blues, Tex-Mex, folk, jazz, and so on — since he was a teenager first learning to play music in his native Boston. He has created his legacy on his own terms, and at his own pace — something not lost on those who view him and his music as the way, and the truth.

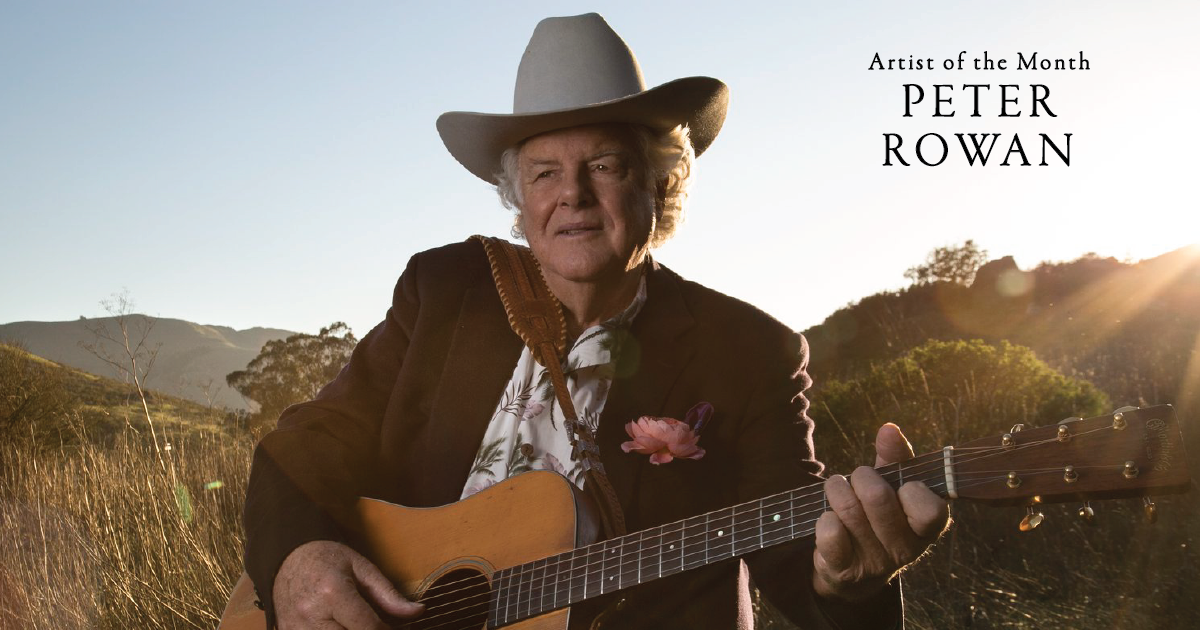

Enjoy the first part of our interview with BGS Artist of the Month, Peter Rowan.

BGS: What are your thoughts about turning 80? I know you’ve never been someone to focus on time itself, seeing as you’ve always looked at everything as “one moment,” you know?

Rowan: Well, somebody [recently] asked me, “How do you feel when you sing the old songs that you wrote in the ‘Land of the Navajo’ days?” — in the late 1960s, driving across America, still haunted by the same ghosts that Jack Kerouac was finding on the road. I was part of that vibe, you know? And I told them when I sing those songs, they’re as fresh to me today as when I wrote them. I’m not reliving them, but I’m keeping alive the experience that I had. I don’t feel necessarily that I have to go into a mode. In other words, I’ve been onstage enough to have fun.

And to get around this little bit of this question of the past and turning 80, I just recorded with Flaco Jimenez again down in Texas, recorded with the band Los Texmaniacs, and they’re all disciples of Flaco. And the kind of polarity that was happening in the late 1970s and 1980s, Flaco was criticized by his own people for playing with me and Ry Cooder. It’s like, the rock/folk pretty much white audience thought it was the greatest thing in the world. But his own community felt that he slightly betrayed [them].

The same thing happened to me when I went to England and played with Flaco. The English critics hated what I was doing because it didn’t fit the mold. I was not a brown person. I didn’t have that look. Everybody associates something with a visual, with a taste. But we were still happy to play. It’s just after a while that was a hard hill to climb, when your fellow musicians believe in you, but the critics are critical of the whole thing. It’s a little bit odd. But now, it’s gone. They’re not there anymore. They’d have to be 90 years old and grumbling at their television, because they were all older than I was [back then].

I’m turning 80, and it’s great to feel like I’m, maybe, leading the pack in some way, as an example of a person who broadened the scope of a couple of things. All of Flaco’s musicians — Los Texmaniacs, Max and Josh Baca, Noel Hernandez — they all grew up hearing Stevie Wonder. So, their Tex-Mex music is way beyond [how it was before].

I think it’s the same thing in bluegrass. I just did a record for Rebel and I’ve got Molly Tuttle, Chris Henry, Julian Pinelli, Billy Strings and Max Wareham [on it]. Some of them aren’t that well-known in the popular imagination of bluegrass because they’ve been doing it on a [certain] level. Billy’s a breakout artist. Molly’s a breakout artist. Chris has been doing it since he was five years old, and he’s never gotten his due.

With the critics, I just don’t pay that much attention. Because, right now, what used to be the complaint is the sort of crossover factor. It used to be a complaint that it’s not pure. Well, how can it not be pure? Everybody who’s playing it now has listened to world music since 1990. They’re all in their late 20s. So, the musicality is still evident. We play Monroe-oriented style — it’s all the lineage through the Monroe style.

It’s that experience of being raised in the internet age, having access to all music at all times, and what that influence does to a person.

Right. And that somebody has the musicality to choose a direction. If I was to say, critically speaking of the jam-grass scene, it’s great exercising your musicality in an open-ended way, right? I guess for the party, for the crowd-pleasing, the stadium-grass — that’s why that happened, because that can happen. People are willing to get out there and bounce around and listen to bluegrass bands. I think the Grateful Dead started a wheel spinning that is just always creating sparks of creativity.

I never learned any Grateful Dead songs except for a couple of verses of some songs, but I got to play with Phil Lesh over the past few years, and I really appreciated his architectural approach to form. I got to sit in with him, and I did it without learning any songs — I got to learn onstage, which is the best way to learn.

And you know, [with playing with Phil], I realized why Jerry [Garcia] liked my songs, because in my songs are a lot of the same chord juxtapositions form-wise that are in he and [Robert] Hunter’s songs. I never realized that before. There are two things that Jerry wrote from; he wrote from fiddle tunes and the blues. And I realized that playing Grateful Dead songs — going into the chorus, “Oh, it’s the fiddle tune part,” going back to the verse, “Oh, it’s the blues.”

Old & In the Way was such a groundbreaking act that blew the doors open in a lot of aspects of bluegrass, country and rock ‘n’ roll music. What do you remember when you look back at that time?

A freedom to record any kind of songs that were emotional, like “Wild Horses” or “The Hobo Song.” In “Midnight Moonlight,” there’s that mysterious little section where there’s a freeform solo going from the key of C back to the key of A. I got that from Otis Redding. That was one of his famous chord changes when he does his outs on those R&B songs. In fact, it’s in “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” and I think it’s in “Shout Bamalama,” too. It’s also the same thing with “Jumpin’ Jack Flash,” passing through that kind of thing as a riff. I thought, here’s a song in the key of A, and it’s using A/D/B minor/D/E/F sharp minor/E/D and then, if you throw a C in there for the solo section, it’s like a complete release from all these chord changes. So, that release became the beginning of these younger pickers going, “Wow, we can play on that for an hour.” Because we used to play 10 minutes on that riff alone.

What sticks out from that experience onstage with those musicians in Old & In the Way?

Well, if it was a local [show], Jerry would be there before anybody with his carton of Camel cigarettes, and Steve Parish [would be there, too]. And you realized that Jerry was an intergalactic traveler, just dropping in on the Earth scene for a little while, but he was totally at home.

I had just come from a band called Seatrain, which was very organized. It was extremely organized. It was great because we rehearsed so much that when we got out onstage you didn’t have to think at all, you could just rock out, you know? Rock ‘n’ roll was the vibe. They were a very adventurous band. All kinds of time movements, changes and kicks, accents. And then to come to Old & In the Way from there was like, “Oh, I can breathe again.” I remember singing the ending of “Land of the Navajo” at the first rehearsal and I looked over at Jerry. He kept nodding his head like, “go.” It was like Jack Kerouac at Allen Ginsberg’s poetry reading at City Lights Bookstore — “go, man, go.” Encouragement, encouragement.

And at our shows with Bill Monroe, you can hear me and Richard Greene encouraging Bill. In bluegrass, you just do the beautiful grace of presenting the music, being good neighbors and all that stuff. But you could hear us in the band going, “go, man, go.” Go for it, that’s where we came from. That’s what Old & In the Way was — the “go for it” signal to everybody.

Editor’s Note: Read the second half of our BGS Artist of the Month interview with Peter Rowan.

Photo Credit: Amanda Rowan