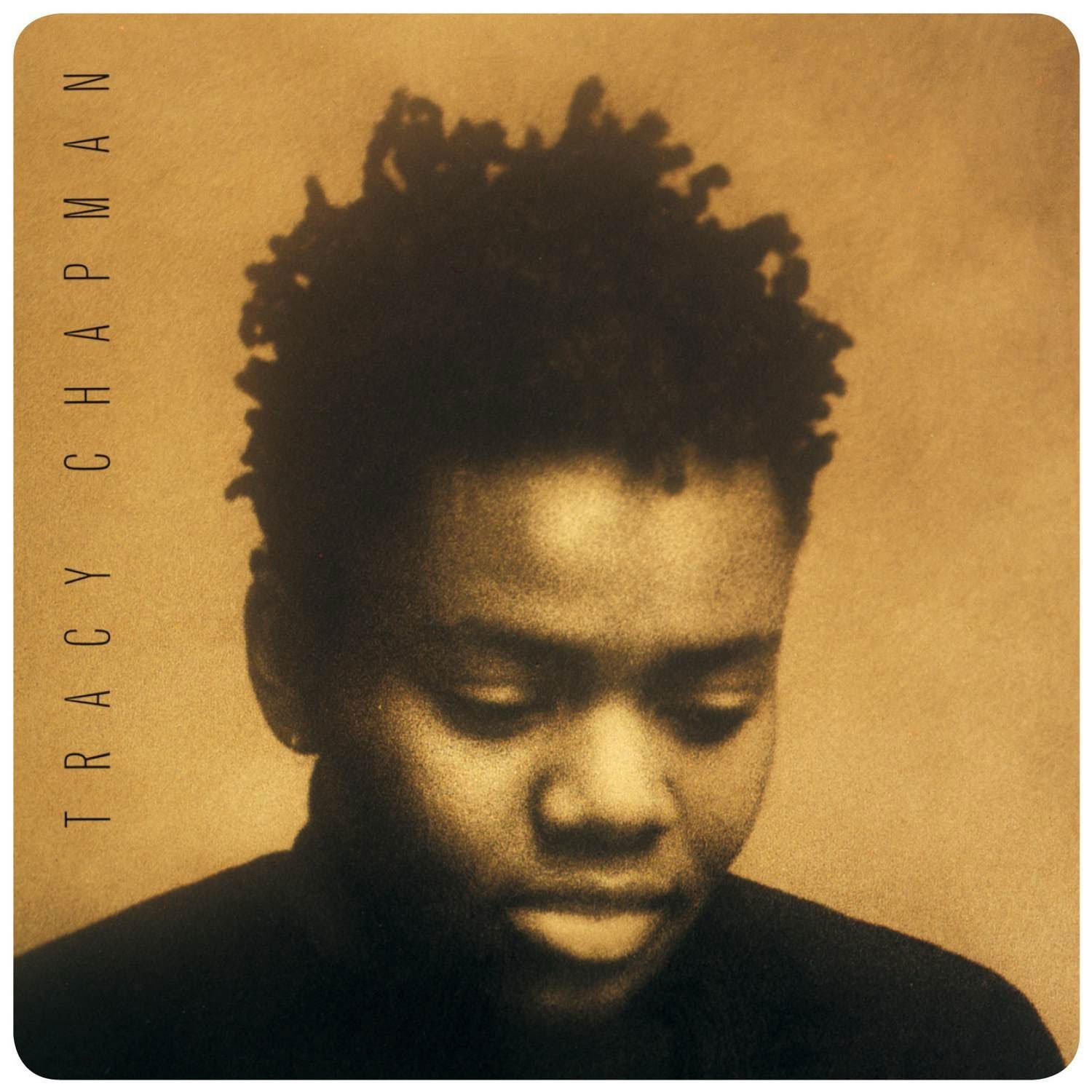

For the week of August 27, 1988, the number one song in America was George Michael’s “Monkey,” a crackling dance-pop tune off his multi-platinum Faith. Rounding out the top 10: Elton John’s “I Don’t Wanna Go On with You Like That” and Chicago’s “I Don’t Want to Live Without Your Love,” along with “Simply Irresistible” by Robert Palmer and “Sweet Child o’ Mine” by a new band out of L.A. called Guns n Roses. Lodged at number six — as high as the song would climb, but still remarkable — was “Fast Car,” by a young singer/songwriter named Tracy Chapman, who just a year earlier was busking in coffee shops around Boston and Cambridge. She had released her self-titled debut in the spring, and “Fast Car” had become a radio hit. She was a curious presence on the singles chart, as she was not a pop artist nor does she play power ballads: “Fast Car” is an acoustic ballad about poverty, hardship, and the kind of dreams that prove more burdensome than freeing.

She was never going to give George Michael a run for his money, but Chapman’s success in 1988 is remarkable for a newcomer making her debut, especially one who chronicles the lives of people who can’t afford to buy albums or cassingles. In “Fast Car,” a pair of lovers determine to escape their hardships together. “We gotta make a decision,” she sings, “leave tonight or live and die this way.” They move to the city, look for jobs, live in a homeless shelter, have kids, continue to struggle as much as they ever did. The end of the song is ambiguous, as the narrator tells her lover to leave: “I got no plans. I ain’t goin’ nowhere, so take your fast car and keep on driving.” Is she giving the driver their freedom? Or has her lover become extraneous, one more anchor weighing her down? Is it an act of love or of its opposite?

Bruce Springsteen is the obvious touchstone, in particular songs from Darkness on the Edge of Town and The River — his grimmest albums with his most desperate characters, many of whom drive fast cars and nurse dashed dreams. In other words, Chapman was not as much of an anomaly on the charts as she might have initially appeared. Just a year before, Suzanne Vega notched a number three hit with “Luka,” about child abuse and our responsibilities to the people around us. And even before that, there was a song that shares a story with “Fast Car,” albeit definitely not a sound: Bon Jovi’s “Livin’ on a Prayer.” As the Reagan era died down in the late 1980s, pop music was reflecting the woes of the country back to itself, and Tracy Chapman appeared in 1988 as the culmination of pop’s newfound social engagement.

Chapman grew up in working-class Cleveland, raised by her single mother who saved money to buy her daughter musical instruments. She began writing songs as a child and, after winning a scholarship to a progressive private school in Connecticut, Chapman began performing at the school coffeeshop. An anthropology major at Tufts, she developed a reputation, locally, as a protest singer, which brought her to the attention of a fellow student named Brian Koppelman, whose father co-owned a major publishing company. Soon, she had a record contract with Elektra and a new manager (who also managed Bob Dylan and Neil Young). Making her debut, however, was much more difficult, because most producers declined to work on a folk album. Eventually, David Kershenbaum, who had previously helmed hits for Duran Duran and Supertramp, accepted the job and promised to keep the music austere and subtle.

The focus is on Chapman’s expressive singing and surprisingly dexterous acoustic guitar playing, which naturally led fans and critics to connect her with the ‘60s folk revival. They’re not wrong, but the comparison is more limiting than revealing. Yes, Chapman sings about revolution and peace and poverty and the military-industrial complex just like Dylan and Baez, but her musical palette is broad. “She’s Got Her Ticket” rides a percolating reggae beat without sounding like a musical tourist. “Baby Can I Hold You” is a domestic drama staged as chamber pop. “For My Lover” is a thumping blues number, with Chapman boasting about spending “two weeks in a Virginia jail … for my lover, for my lover.” (Given the persistent and unseemly speculation about Chapman’s sexual orientation, it’s tempting to hear that song as a gay blues, which would place the song in the tradition of Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey.)

Perhaps the most startling moment on Tracy Chapman is “Behind the Wall,” which she sings a cappella. It’s a story about domestic abuse, the narrator describing the violent arguments she hears coming from the apartment next door, and the lack of any accompaniment contrasts the noise that keeps her up and eventually draws the police. Chapman pauses between the lines of the verses, letting that silence scream loudly, yet the song is as much about how society ignores or disregards the dangers faced by women, in particular black women: “It won’t do no good to call the police, always come late, if they come at all.”

Not everything is quite so powerful. Some of Kershenbaum’s flourishes anchor the music to 1988, in particular the sitar on “Baby Can I Hold You.” And, occasionally, Chapman skirts actual outrage for naïveté, especially on “Why?” “Why are the missiles called peacekeepers, when they’re aimed to kill? Why is a woman still not safe, when she’s in her home?” Her desire for safety and community are sound and all sadly relevant today, but the rhetorical structure of the song does them little justice. Answering rather than simply asking those questions would make a more substantial song. Chapman had been working on many of these songs for nearly a decade, back when she was at that private school in Connecticut. There is a youthful idealism animating many of them, which is at odds with the harsh realism that animates others. That tension gives the album an electric jolt, even 30 years later. Tracy Chapman is the sound of a young artist clinging to her optimism, even in the face of so much cynicism.

Tracy Chapman peaked at number one on the album chart and earned three Grammy nominations, including Album of the Year. She lost to George Michael, but did pick up a trophy for Best New Artist. Also in 1988, she appeared on the Amnesty International Human Rights Now! Tour, on which she shared a stage with Springsteen, Sting, Peter Gabriel, and Youssou N’Dour. Was it all too much too soon? Chapman’s follow-up, Crossroads, released a year later, was arguably better than her debut, but sold fewer copies. She enjoyed a massive hit in 1995 with a 12-bar blues called “Give Me One Reason,” but it seemed like a fluke. Gradually, Chapman’s musical protests grew more general: Songs like “The Rape of the World” and “America” are as broad as their titles, less rooted in story and character, no longer enlivened by the well-observed detail or the thorny insights. As of this writing, it’s been a full decade since she released an album of new material, and yet, Tracy Chapman sounds as sadly relevant as ever.