I first heard Sam Bush in the early 2000s — I was 11 or 12, probably — when my dad brought home Glamour & Grits. The CD jacket was a minor epiphany. Here was this wildcat-looking guy wearing big, black shades and a cheetah print headband. In his hand was a busted old Gibson mandolin. Not a Les Paul. Not a Strat. A mandolin. Something in my tiny little music-obsessed mind said "DOES NOT COMPUTE."

From there, I found New Grass Revival, the genre-expanding string band founded in the early '70s. I started with On the Boulevard, featuring R&B expatriate John Cowan and a very cute-looking banjo player named Béla Fleck, and moved on to Fly Through the Country, where Sam’s Duane Allman-inflected slide mandolin solos gave my pubescent mind something else to struggle to categorize. Through my teenage years spent banging on guitars in garage bands, it was Sam Bush who kept me holding out hope that there could be something interesting — something cool — in the otherwise hokey genre my dad loved called bluegrass.

Though I wasn't around to witness the string band world of the '70s, I’ve learned to revere those heady days. All my heroes were buddies: There was John Hartford, the hip eccentric with steamboat stories; Norman Blake was the traditionalist who looked more like a train conductor with his wire-rimmed glasses and worn-out shoes; and Tony Rice landed somewhere near Richard Petty on the redneck scale and mostly dressed like a lounge singer, but he and David Grisman had dominant 9th chords, goddammit, and they weren’t afraid to use them. Sam Bush, on the other hand — Kentucky-born mandolin-toter though he may have been — was cut from a different cloth. He was rock 'n' roll, 100 proof, who managed both to piss off Bill Monroe (“Stick to the fiddle, son”) and to introduce the Big Mon’s licks to a new generation.

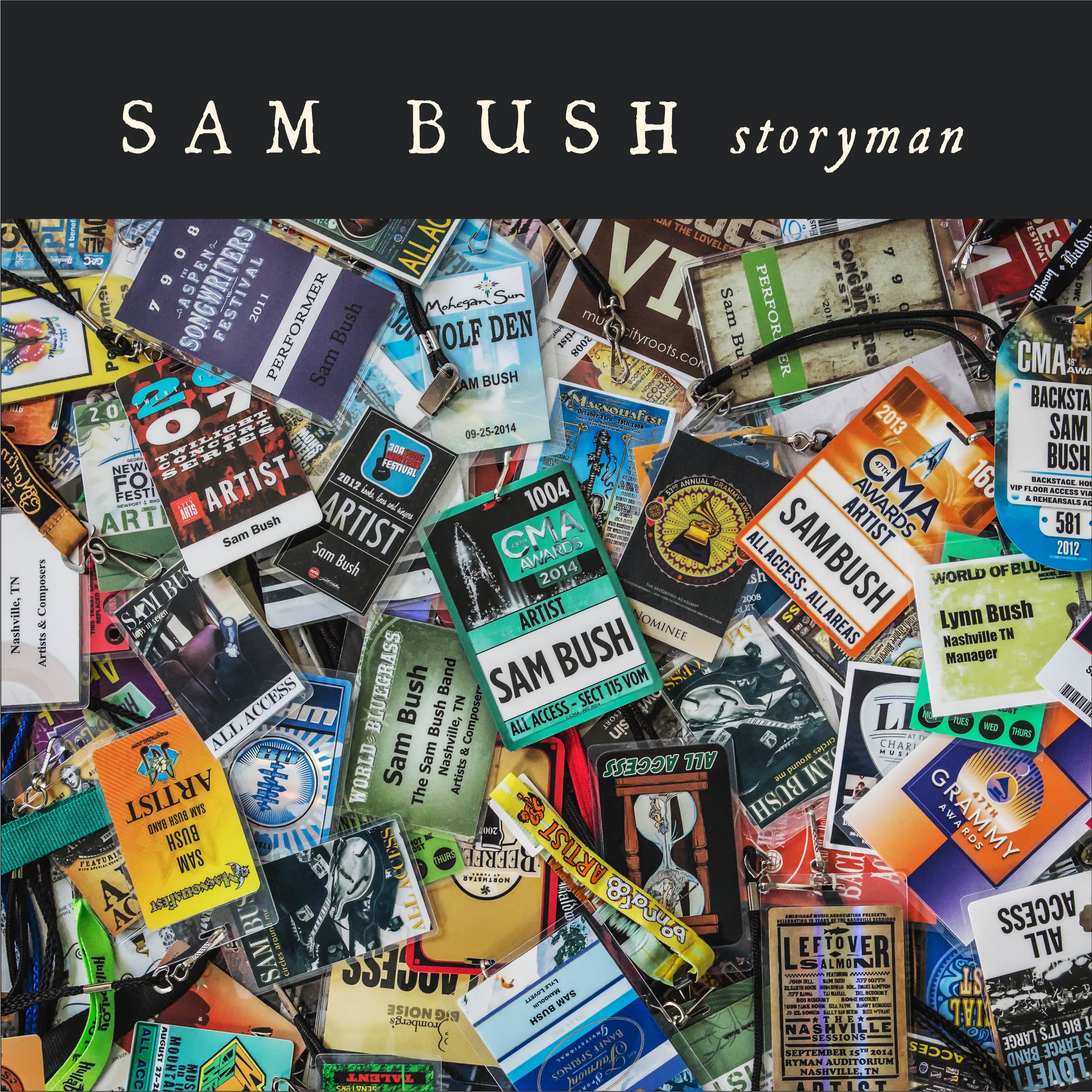

I got to talk with Sam this week about his new record, Storyman. We touched on his songwriting process, festivals in the 1970s, and the future of his instrument of choice: the mandolin. These days, 46 years into his career, he’s often praised with patriarchal titles — Father of Newgrass, King of Telluride — but while he embraces his role as elder statesman, I got the sense that he mostly thinks about playing music, discovering new records, and writing songs with new friends or old heroes — for a man in his fifth decade of professional music making, he still brings to the stage a surprisingly joyful, boyish energy. In fact, if you see him off stage at a festival, he’s probably jogging to another set, mandolin case in hand, floppy curls bouncing above his unmistakable grin. He’s still loving it, even after all these years.

I’m struck that Storyman really showcases a band. It’s not just a backing band, but a band band.

Absolutely, yep. And that’s my love. That was my first wish as I tried to accomplish this singer/songwriter record. Really, my favorite musicians I get to play with are those four guys. We’re all in a band together.

That’s cool. It’s a pretty eclectic batch of tunes.

We did a couple of different treatments on this one, with an out-and-out country shuffle song on the duet with Emmylou [Harris], and then a Jimmie Rodgers kind of song with the one Guy [Clark] and I wrote, "Carcinoma Blues." Within our group, keeping it all acoustic, that seemed to be another thread to follow. Because I love to play electric music and to mix the two, but these songs were all definitely acoustic-style songs to me, so in that way, the obvious choice was our band.

Guy Clark and Emmylou Harris are a couple of my favorite songwriters. What was it like writing songs with those two?

Guy was the most masterful songwriter I’d ever worked with. With Guy, it’s kind of like the way he made his guitars: simple, to the point, not one wasted chisel. He liked his guitars plain and unadorned, just like his songs. And with Emmylou, you know, I played in her band for five years, so she’s taken on the role of big sister for me. For us to write together and sing together, it’s really a comforting feeling.

So there’s the country-style song, “Handmics Killed Country Music,” with Emmylou, and there’s even a little reggae thrown in there on “Everything Is Possible.”

Yeah, that tune with Deborah Holland! Steward Copeland and Stanley Clark and Deborah Holland, the three of them were in a band called Animal Logic. She’s a tremendous talent. So Deborah and I wrote this tune a number of years ago, and she had these real positive lyrics already going, so we said, we need to make this a Bob Marley-sounding song. So we put it together.

Funny you mention Bob Marley. When I was a kid, my dad’s two favorite bands were New Grass Revival and the Wailers. And you guys played Marley tunes, so I grew up thinking that combination of newgrass and reggae wasn’t weird at all. But sometimes people talk about you as if you dip your toes into separate styles — a little bit of reggae, a little bit of country, a little bluegrass — as if the genres are a buffet line. Do you think of those divisions when you’re arranging or writing a tune?

I don’t think about the genre divisions when we’re actually sitting and arranging. And that’s fine with our band, because there are different areas we can play in, so we’re fortunate that we can just think about the song. The way these songs were written kind of dictated the arrangements.

How was the recording process?

Really, we just went into the studio down in Florida, and the way the banjo and mandolin solos sound, that’s the way we played it that day. Boy, when you think of it, Scott Vestal is kind of the star of the record to me. He just plays so beautifully. His parts, his banjo picking is just perfect to me. I never suggest anything for him to play, and Stephen Mougin the same way. As Stephen and I were writing “Play by Your Own Rules,” we were trying to find a little fiddle tune-style melody to go with the lyrics. Those kinds of songs really turn me on. I guess we’ve got a couple of those on the record, that one and the one called “Bowling Green.”

Your hometown, right? Tell me about that one, “Bowling Green.”

On that one, Jon Randall came over to the house one day and he already had most of the first verse written, which was about my mom and dad, of all things. [Laughs] He had me and Lynn in tears. I said, "Well, hell, let’s finish that one." In that one, we specifically mention a couple of fiddle tunes. My dad, man, he loved the fiddle. God, he couldn’t have enough fiddle. His favorite tune in life was "Tennessee Wagner" and he just called it “The Wagner.” He loved fiddle contests, and all the Texans would come up to the fiddle contests and they would add an extra chord to the song. So my dad would say, “I don’t want to hear that 'Texas Wagner.' I want to hear the one from Tennessee!” So that’s why the song says, “He loved to saw 'the Wagner' / The one from Tennessee.”

That’s cool that it’s an homage, not just to those fiddle tunes, but to the music in your family.

Yeah, and that song’s true, you know. We would work in the tobacco fields and come in for the midday meal, which wasn’t lunch — it was dinner. And then at night, it wasn’t dinner — it was …

Supper!

[Laughs] Supper, that’s right. So we’d come in for dinner and we’d play a tune or two. It’s all true. Then we’d listen to the Opry. It’s just like the scene out of Coal Miner’s Daughter. We’d sit around and listen to the Opry on Friday and Saturday nights, gathered around that radio. My dad would just sit and wait for somebody to play a fiddle tune.

You know, I grew up with a lot of music, including some bluegrass, but I’m still pretty new to the insider’s bluegrass world. I’ve been to the last few IBMAs, since they’ve been held in Raleigh, and it’s always cool to see the mix of bluegrass communities that come out of the woodwork. From the real dyed-in-the-wool traditionalists from Southwest Virginia, to the Colorado folks with Grateful Dead T-shirts on …

Yeah, and that’s been true for all of my professional life, which started in 1970 when I got out of high school. That Spring, before I graduated, I went to the Union Grove Fiddle Festival, and that was the first time I found hippies out in the field playing. They were called the New Deal String Band from Chapel Hill. They were a little older than me, and I made pals with them. Of course, there were old-time traditionalists. You had the hippies and rednecks, the young people and old people. And that’s the great thing about acoustic music, bluegrass, old-time, folk music — the music was the tie-in. It isn’t just for one age group. I’m hoping this record is that way, too. It’s not for one age group.

I’ve heard Union Grove was a wild time back then. A lot of folks think of ’71 at Camp Springs, too, as a real watershed moment when you and Tony played with the Bluegrass Alliance. Now it’s been 45 years. Did you know it was a big deal at the time?

No, we were just trying to stay in tune! Camp Springs in ’71 — now looking back I know that, right around that very weekend, a lot of things turned around in bluegrass. Tony Rice’s last performance with the Bluegrass Alliance was that weekend. Tony was leaving our band to join J.D. Crowe’s band. That was a big turnaround in bluegrass music when Tony went on with Crowe. And the reason J.D. Crowe’s band had a vacancy is cause Doyle Lawson left Crowe to join the Country Gentlemen. And the reason there was a vacancy in that band was because Jimmy Gaudreau left the Country Gentlemen to form the Second Generation with Eddie Adcock. I mean, four bands turned around within a month.

And then, within two months, the Bluegrass Alliance became Newgrass Revival. Probably within the next year, they started getting the Seldom Scene going in D.C. And you still had the New Deal String Band over in Chapel Hill. And the Osborne Brothers, to me, were just outrageously great then. They were totally the kings of progressive bluegrass-style music. So those early '70s were really important. But right off the bat, it was obvious to me that bluegrass-style music wasn’t for one age group. It wasn’t for one type of person. And it doesn’t revolve around trends. It revolves around people learning to play and sing.

Talking about trends and tradition reminds me of Nick Forster’s speech at IBMA last year, where he said something like, “I love the Earls of Leicester, but we should realize that we gave our Grammy to a cover band …” What do you think about that? Too much homage being paid to the traditional stuff?

You know, I think bluegrass-style music has been in a good spot for a while now. Unfortunately, we just lost Ralph Stanley. I was privileged to see the Stanley Brothers in ’65, and, when I first saw Ralph, I knew I was seeing an incredible musical force, and he always has been. And he sure will be missed. But we still have some of the greats. The next great king of bluegrass for me is Del McCoury, and boy is it resting in great hands. And, of course, the Travelin' McCourys are a force — and then you think of Sierra Hull, and way on the top of the scale, the Punch Brothers, and then over on the West Coast, David Grisman has the David Grisman sextet, and then on the rock 'n' roll side, you’ve got the Sam Bush Band. We all give a nod to old-time bluegrass all the time. Too numerous to name them all because they’re all great — and anybody younger than 50, I think of them as the young bands! Within the world of bluegrass, the variety is pretty healthy I think.

I just saw Sierra play with the McCourys at DelFest, and, man, she’s great. I’ve seen you a few times now at Tony Williamson’s Mando Mania workshop at Merlefest. I take it you’re feeling good about the future of the mandolin?

Oh, the future of the mandolin is really rolling right along. Tony Williamson does such a great job with Mando Mania because, every year, he introduces me to a new, young player that I haven’t met. So Tony’s the one out there with his ear to the ground paying attention to all the young mandolin pickers, and, once again, he brings someone new that I haven’t met before that I’m always knocked out with.

As far as mandolin itself, I hesitate to start naming mandolin players because I’m a fan of all the young pickers. Now, with the advancement of people like Adam Steffey and Chris Thile, and now Sierra Hull — I see her as kind of having learned from Chris and Adam — the bar is being raised. I’m fascinated by the things they can play. I’m just glad to be in there somewhere!

You think [Bill] Monroe’s style is going to stick around alongside all the modern stuff?

As far as Monroe style, you know, that’s alive and well very much in the hands of Ronnie McCoury, Roland White, and especially Mike Compton. I really believe there will be people that always will want to play like Bill Monroe. Actually, it’ll be interesting: I think in the next 20 years we may see more people playing like Monroe than we have lately. The same way that guitarists love to dig up stuff from Muddy Waters and Elmore James and Skip James, you know, Freddy King and Albert and B.B. King. The way guitarists are honoring them, I have wondered if there might be a resurgence in Bill’s style, the same way that all banjo players want to play like Earl Scruggs.

Thinking of all the distinct styles of heroes like Scruggs or Monroe — you know, the first name guys, Doc [Watson], J.D. [Crowe], Clarence [White] — they sound now like they came up with their own style out of whole cloth.

Yeah, true.

A lot of young folks nowadays — and I mean friends of mine, great pickers — are coming out of programs like Berklee. Do you think there’s anything lost with the more conservatory-style instruction?

No, I think it’s just a different way to look at it. Once again, it sure hasn’t hurt Sierra Hull to go to Berklee for a couple years. You know what, great musicians come from both areas, whether you were schooled or simply learned by ear and are following the traditions. What’s the old joke? “Can you read music?" "No, not enough to hurt my playing.” Or, "How do you get an electric guitar player to shut up in the studio?"

Show him some sheet music?

[Laughs] To me, I mean, I chose to start playing after graduating from high school. I chose to move to Louisville from Bowling Green, Kentucky, and I started playing five or six nights a week in a bluegrass band. I was either going to go to college and play violin or do that. And I chose the more improvisational side. Of course, they’re both valid, but for myself, I believe I chose correctly. I tell you what — nothing will make you tighter than five nights a week playing in a bluegrass band. You spend a number of months in the wintertime doing that, when you hit your first festival, you are ready. You have done your homework. It was that way with New Grass Revival. When we recorded our first album, we were playing so much that, when we hit the studio for our first record, I know we did the whole thing in three days. We knew those songs — bam! — like the back of our hands. We were ready to go.

Any new stuff outside of bluegrass you’re digging these days?

You know, my listening tastes are pretty eclectic, I guess. Let’s see, what am I into these days? John McLaughlin’s new record called Black Light. The new Eric Clapton record called I Still Do has got some really great stuff on it. There’s a record called D-Stringz, and it’s Stanley Clarke on bass, Biréli Lagrène on guitar, and Jean-Luc Ponty on violin. And then, on the other side of the coin, I’ve been looking for this Country Gentlemen record on Mercury called Folk Session Inside forever … for I don’t know how long. Lynn and I walked in a great record store in Louisville, Kentucky, called Matt Anthony Records, and there it was — for eight dollars. [Laughs]

Man, that’s a good feeling.

So I finally just got Folk Session Inside — I’d had a tape of it, of course, but I’d never owned the record. Just when I least expected it, I was walking out of the store with that Country Gentlemen record and I was totally thrilled.

Photo credit: Shelley Swanger