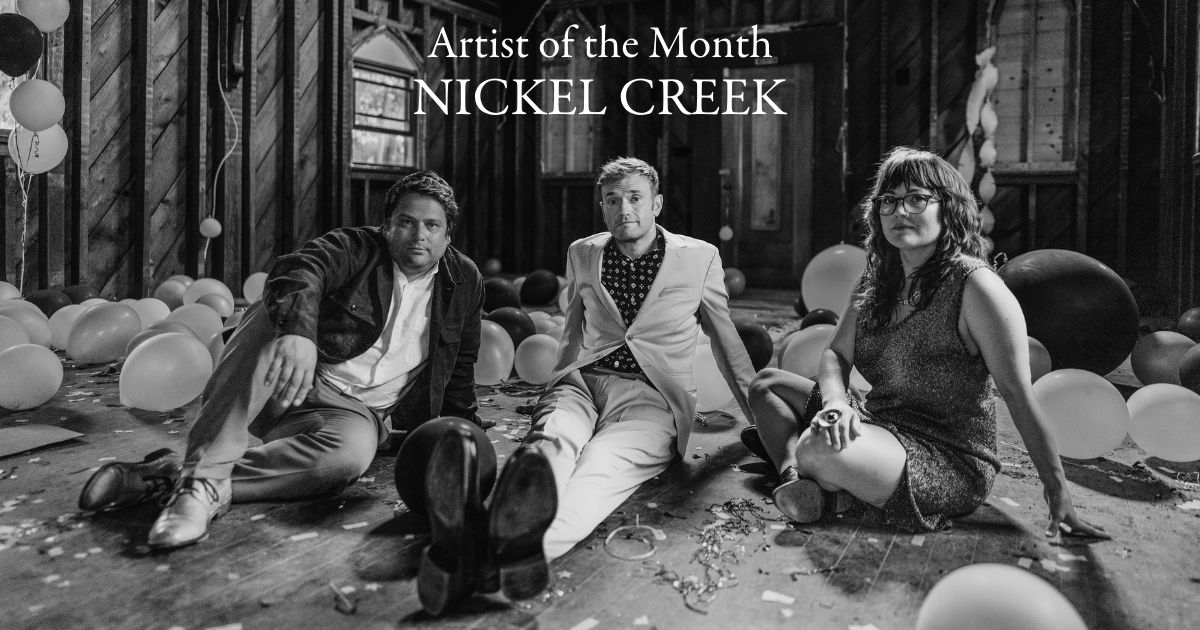

It’s been nine years since Nickel Creek’s last album, and the band will remind you of that at the very start of their new one, Celebrants. “My God it’s good to see you, right here in the flesh,” they sing on the title track. Of course, they can’t actually see you through your turntable or car stereo, and you weren’t actually there in the flesh when the trio recorded the song, but that doesn’t decrease the joy and intimacy they bring to that hearty welcome. It’s a gambit both clever and joyful, not only ushering the listener back into their world but implying there is no Nickel Creek without an audience.

Or, perhaps, they’re singing those lines to each other. Maybe it has nothing to do with us and everything to do with these three remarkable musicians who’ve been playing together for nearly forty years and recording together for more than twenty. They’ve spent most of those decades apart, however, so maybe they’re just happy to be in the same room together again.

Such ambiguity is fascinating, lingering in your mind as they lay out the stakes and the mechanics of Celebrants: “We can turn the stuff we need to get off of our chests into something we can sing through.” This is a heady album, full of big ideas, strewn with easter eggs, erected with repeated lyrical and musical motifs. It’s rich, complex, self-referential, immersive — less like a short-story collection and more like one of those big postmodern novels/doorstops, like House of Leaves or Underworld. It’s the kind of the album you could map out on a large whiteboard and then alienate friends with your wild theories about who exactly they’re canonizing on “Goddamned Saint.” Or you could let all that slide right off you and just revel in the virtuoso playing, the intimate harmonies, the rousing choruses.

“Right up to the last minute,” says guitarist Sean Watkins, “we were still adding things and connecting dots and trying to have as much sharing as possible between the songs. That’s very different from the way we usually write.”

In the second of our Artist of the Month interview series with Nickel Creek, Sean talked to the Bluegrass Situation about loving The Smile Sessions and Kendrick Lamar, trusting his bandmates, and making an album like a video game. Look for our conversation with Chris Thile in the weeks ahead and enjoy our Q&A with Sara Watkins.

BGS: What sparked the desire to sort of rekindle Nickel Creek at this particular time?

Sean Watkins: It’s a few things. Our life schedules opened up, for one thing. But the instigating moment was in 2020, early in lockdown, when we were asked to do a group interview with NPR. They were putting out a story about the 20th anniversary of our first album. We hadn’t realized it had been so long. We got on this group call and waxed nostalgic. And it was really fun. Sara, Chris, and I are so close. Obviously Sara and I are siblings, but we all have one of those relationships where you tend to not prioritize the thing you assume will always happen, like us getting back together. And so you don’t really focus on communicating and talking all the time. But when we do get back together, it’s like no time has passed. It’s like we just saw each other last night. During that phone call, we realized how much chemistry is there, how much we all love each other.

At that time we all had a lot of free time because of Covid. We decided that when we could, we wanted to spend a lot of time writing and dreaming up the biggest, most ambitious project we could. We ended up getting together to write in February of 2021 at a friend’s vacation house in Santa Barbara. Chris drove cross-country with his family and dog. We were there for two weeks, then we were at Sara’s house for another two weeks. So we did a solid month of writing. We’ve never spent that much time writing. After that we’d do a week here, a week there, five days here, five days there, some in LA and some in New York. I think I counted up 75-80 days total that we were together. We were able to really hunker down with each other and figure out where we are musically and personally. And we were able to reconnect. That became one of the central themes of the album — reconnection.

That’s grounded in the very first song, where you could be talking to the audience or to each other. It’s very poignant way to start your first album in nine years.

We were celebrating the reopening of… well, life. But it’s also a celebration of our reconvening as a band. It’s been so long. At that point it had been seven years since we’d toured together. And now it’s been nine! “Celebrants” was actually one of the first songs we worked. On the first day we had that lyric, “My god, it’s good to see you!” From the get-go, we wanted that to be the opening line on the opening song of the record.

It sounds like you weren’t writing songs so much as you were writing a whole album.

All of the songs we wrote point to other songs. They’re all related. They have counterparts. The first night we got together, it was my birthday, and Chris’s birthday is two days later. We always have a joint birthday party. So we convened at the house in Santa Barbara, and after the kids and significant others went to bed, the three of us stayed up with cocktails and just mused about what we want to do. We all wanted to take a big swing, but we needed a direction. One of the albums that we’ve always loved and been inspired by is The Smile Sessions, which would have been a Beach Boys album but Brian Wilson never finished it. We’ve all loved it for so long. It’s been part of our shared musical folklore.

How did that play into Celebrants?

One thing we love about it is its unfinishedness. It points to some great mystery about what it could have been. It’s like a Choose Your Own Adventure book. He’s mixing up themes, and some songs are borrowing from other songs thematically and lyrically. That was something that we really wanted to try. All of these songs have some element of some other song.

Such as?

One example would be “Failure Isn’t Forever,” the last song on the album. There’s this ghostly vocal that’s kinda in the background. That’s the first song popping back up again. There’s a lot of that. We tried to do it as much as we could on this album.

I feel like you’d need a spreadsheet to track it all.

Ha. We did have a group note going, a shared note with all the lyrics. It still exists somewhere. We could be constantly working on it and updating it and talking about it. And at the top of it was a mission statement, which is printed on the album. I can’t recite it word for word, but it’s about embracing the friction inherent in any meaningful relationship. That idea was a thematic arrow pointing us to what we wanted to explore.

But it was definitely a lot to keep track of. Right up to the last minute we were still adding things and connecting dots and trying to have as much sharing as possible between the songs. That’s very different from the way we usually write. What you want to avoid when you’re making an album is copying yourself. Instead of avoiding that, we leaned into the idea. We leaned into repeating themes and melodies and lyrics. Once we decided to do that, it opened up a whole world of possibilities for us.

It makes for an interesting listening experience. You can’t really take it all in with one spin. You need to spend time with it and let it reveal itself over time.

That’s the dream. It’s going to hit everyone differently, but we really wanted there to be a lot of depth to it, a lot of easter eggs. We tried to create a video game where you have a whole world to explore. You can wander around and look under rocks and see what’s over that next hill. There’s always new things you can find and characters that relate to each other differently. I’m not a gamer, but that metaphor makes the most sense to me.

Were there any moments where the album revealed things to you that you didn’t intend or maybe didn’t catch the first time around?

There’s a moment on “Failure Isn’t Forever.” My wife had the album on in our house. This would have been a couple of months ago. That song played, and I’d forgotten that we’d added that line from the first song to the last song. There were just so many different ideas flying around. And there were so many different versions of these songs that we recorded. We did an early version of the song in front of one mike with Mike Elizondo, who played bass on the album. We were writing and recording, and the songs were very rough when we first put them in order to see if they would work. It was our proof of concept.

Then we came back again with our producer Eric Valentine a few months later, and we did another practice swing. We tried out some different ways of recording, with some different gear and microphones. Eric figured out that he wanted to make this album mostly on ribbon mikes, and he used his old RCA console that had a very particular sound that was really, really cool. So we made the album all the way through, ended up cutting one song, and replaced it with another instrumental. Then we had a framework, a blueprint. Then we went into RCA Studio A in Nashville and made the bulk of the album there. That was a year ago last April or May.

It sounds like this could have turned out very differently. This is just one iteration of a million different outcomes. I guess that’s true of any album, but it seems more dramatic in this case.

There’s a ton of moving parts. Usually the thing that holds us back from letting a project be what it wants to be is time. You don’t always have the time to keep whittling away at it, and at a certain point you just have to stop. Inevitably you’ll find some things you wish you’d done differently or hadn’t done at all. But because we had all that time and the ability to record these songs and hear how they came out of the speakers and how they sat in sequence, we were able get it as close as possible to what we wanted. No project is ever going to be perfect, but this is the closest we’ve ever come to putting out something that just feels complete.

Aside from playing different instruments, what is your working relationship with Sara and Chris? What’s the breakdown of labor?

There are no set roles. We all play different parts. It’s like a marriage. It’s like any relationship. Sometimes one person is directing traffic on a project, and the others take a more supportive or editing role. And sometimes you go back and forth, because no one person can do everything all the time. There are a few songs on Celebrants where one of us had a start. Like “Holding Pattern.” I had the two guitar parts and some lyrics that I wasn’t super proud of. I played it for Sara and Chris, who were throwing out ideas. And I remember this little song start that I had on a voice memo, and they both loved it as a chorus. Chris had an idea for a lyric, and he said he would love to sing it. It was great. It became one of the more obvious songs about Covid, where we’re all holding each other through this long slog. It was completely different from the original idea that I had. And it was so much better.

That’s the beauty of a band — especially a band you can trust. We all come from similar places, and there’s so much we have in common, but no one has the same musical experiences as the others. That’s always been a fun part about writing in this band. You can be surprised by new ideas that the other two will have. It’s very gratifying. It comes down to being around people you love and trust.

There’s such a wide variety of sounds on this record. Certain songs sound almost psychedelic, while others have something like a hip-hop vibe in the way the words and melodies are delivered.

I know what you mean. I hesitate to use the word “rap,” but there are interesting ways that people phrase lyrics. Kendrick Lamar really phrases his stuff in a particular way that’s really exciting. I will say that the ways these words were put together was very much a part of the writing process. It wasn’t like, “Oh, we’ll figure out how to phrase that later.” It was like, “Here’s how it’s going to work with the timing of this song and the timing of the lyric, with us singing harmony counter to the rhythm.”

As an instrumentalist, how do you keep challenging yourself without making chops the whole point of it?

When you first start out playing bluegrass, it’s all just about chops and flashiness and playing fast and clean. That’s great. But as you grow older, that becomes less interesting. What becomes more interesting is how the song makes you feel. You want to keep those abilities, but you realize that it can be a little surface-y. There’s a time and a place for raging, and I think the two instrumentals on the album have a fair amount of that. But sometimes you want more feeling and nuance, so you have to do different things. Sometimes that means playing very few notes, like in “Holding Pattern.” That mandola… it’s not even a solo. It’s just a melody that happens in the instrumental section of the song. It’s the melody from “To the Airport.” It’s very sparse, yet it’s got a modal quality that reminds me of an old English folk tune. That song required very, very few notes, and that’s what conveys the feeling.

Photo Credit: Josh Goleman