Lake Street Dive rather famously borrows a little bit from a lot of things. At times exuding an old school R&B vibe, at others a bright pop sound, their music is equal parts the Beatles and Motown, with a bit of brassy big band thrown in for good measure. Where that kind of uncategorized approach might sound messy — even noisy — under another band’s thumb, Lake Street Dive doesn’t lose track of their identity, even as they pepper it with myriad influences.

The classically trained four-piece includes guitarist and trumpeter Mike “McDuck” Olson, upright bassist Bridget Kearney, drummer Mike Calabrese, and vocalist Rachael Price, whose bluesy alto grounds whatever musical path the band explores. Lake Street Dive is set to release their third studio album and Nonesuch Records debut, Side Pony, on February 19. Produced by Dave Cobb (Jason Isbell, Sturgill Simpson), the album involves new risks — like challenging time signatures — alongside the jazzy approach to pop the band has played heretofore. It’s a step forward for the band but, as Olson explains, not a new direction.

I’ve got to ask: Where does the nickname “McDuck” come from?

Oh, it’s an old college nickname. I had mono when I moved into the dorms [at the New England Conservatory of Music] my first year, so instead of being friendly and looking to make new friends like Mike Calabrese was, I told everyone to go away and leave me alone while I got better. I earned the nickname "Scrooge McDuck." Fortunately, the McDuck is the only part that stuck.

Stephen Colbert took a liking to your sound when he hosted The Colbert Report, and he recently invited you back to play The Late Show . What was it like performing for Colbert again?

It was sort of a double-whammy return because Colbert’s show is in the Ed Sullivan Theater, which is also the theater that Letterman taped out of, so it was cool because it was kind of like playing Colbert on steroids. It was also cool to be back in that theater that we had done the Letterman show in. It had been redecorated, and a lot of the same crew people are still working the show, so it was nice to see some of those guys again. It’s fun, too, because we’re not quite as nervous as we used to get, although we’re not completely immune to it. I’d say that I don’t have the same mind-numbing terror going on TV that we used to when we did the first Colbert taping.

One of Side Pony ’s singles, “Call Off Your Dogs,” shows an interesting approach to meter and rhythm compared to the band’s earlier work. Where are you drawing that inspiration from?

The main riff, which is in 3/4 time, came out of Bridget’s fascination with … it’s sort of two-fold. She spent some time in Africa studying music from Ghana and she studied abroad in Morocco as a college student, combined with a bass player’s innate love of Motown bass lines a la the Jackson 5. The composition, in its first version, was all in 3 and had a trickier rhythmic framework.

Then, when we went into the studio to record it, Dave Cobb didn’t encourage us to stay tricky. He’s someone for whom pop music is candy, and he encouraged us to keep some of the trickier musical elements because that’s interesting for people who are in tune with that, but then say, "Okay, if you’re going to have the tricky 3/4 verses, we gotta go into 4/4 on the choruses." Because that’s what’s going to get people up and dancing — that’s the fist pumping. So it was a combination of this sort of studiousness on Bridget’s part, and kind of the polar opposite lack of studiousness on Dave’s part that made us combine those two elements in the studio.

The way the verses and chorus oscillate back and forth with one another, rhythmically, is so interesting. It took me a second to wrap my head around what was happening when I heard it.

It’s nice, too, because we’ve been playing with the disco thing. On its own, the disco thing is very dated. If you release a song that has a straight-down-the-pike disco feel in the drums and guitar parts, it immediately makes people think, "Oh great, leisure suits, the light-up dance floors." Stuff like that. We were reticent to do something that was so derivative of one specific thing just because we don’t like to pigeonhole ourselves. So to blend something so immediately identifiable as disco with something that’s a little bit more intellectual made us feel better about using both elements in the same song.

Speaking about elements, the band rather famously deals in many sounds and influences. How do you keep everything from becoming too chaotic, either in a song or across an album?

I think part of it is that we aren’t necessarily, you know, we’re not studio musicians. If someone needs a country track or someone needs a disco track or someone needs a straight-up Motown track recorded for someone’s record, they’ll call people who are skillful in recreating those styles faithfully. We just aren’t that good at recreating something verbatim and, fortunately, that has worked in our favor. We have our idiosyncrasies that we, if not fall back on, then are actually very comfortable in. So it’s sort of like we’re filtering all of these omnivorous style dalliances through this far more narrow Lake Street Dive sort of sieve. It’s also what we enjoy doing and what we think is fun, what parts we think are most fun to play, and those end up smoothing out the edges of something that is more rigidly stylistic.

Well, that’s what makes it so interesting. I’ll listen to a song and pick out three or four influences, but under your umbrella as Lake Street Dive, it all comes together in this new way. It isn’t chaotic, but in another band’s hands, it could easily devolve into a mess.

Well, sometimes it feels like a mess, but I’m glad it’s not coming across that way.

In your composing or songwriting process, is it the four of you together banging something out, or does someone bring up an idea first?

The kernels for a song idea will come in from an individual. All four of us are pretty avid and voluminous songwriters. It can be something as simple as a hook or, in the case of “Call Off Your Dogs,” a rhythm and a bass line. Or it can be a completely realized song with the lyrics, the form, the solos, all this stuff written out. When it comes to the band for the purposes of learning, that’s when the arranging takes place or, in the case of the studio, we did end up doing a lot of writing together, but it all came from a kernel someone had come up with on their own. We don’t sit around and bang out ideas, you know, staring at each other awkwardly across acoustic guitars. That has never been our method.

Isn’t that how the best songs have been written? Awkwardly staring at someone?

[Laughs] Isn’t that how the Lennon/McCartney thing worked? I don’t know. It’s not for us.

So then, from your perspective, what kind of subject matter interests you as a songwriter?

We tend to use pretty familiar pop tropes as, at least, a starting point. We’re not going out on too many limbs here with subject matter, you know; we’re not writing protest songs. It all boils down to love in one way or another, either found or lost. There’s already been 80 years of pop music based on love found and lost. It’s a pretty deep well and, as far as we’re concerned, it’s not been exhausted yet. Until it is, we’re going to keep writing love songs.

It just so happens to be this quirky perspective, which distinguishes you from the major songwriters focused on that very subject.

It is about finding your filter that you want to apply. It’s not satisfying as songwriters — nor is it satisfying to listeners — to hear a song that’s the same kind of lens. They’re all love songs, but they can be viewed through talking about love as self-examination in the modern era — like “Self Portraits” talking about selfies and things like that. It can be sort of veiled and derived through the study of classic Beatles songs, like “You Go Down Smooth” is. As students of music, we enjoy challenging ourselves and each other to come up with as many different ways to explore this well-trodden subject matter, because it’s just more interesting for us that way, and we’re in it for the long game, too. Shame on us if we let it get boring.

If you’re talking about filters, my takeaway is that yours tends to be much more intelligent than what the average love song purports itself to be.

I hope so, but it’s also … it’s an extremely luxurious position to be in with four songwriters in the band, because we all write. We’re not like Carole King who went into the office everyday and, as a professional songwriter, generated hit after hit after hit. All four of us, we have our hits and our misses, but because there are four of us, we have a lot more hits to choose from. We tend to scrape off the very best from the top, which is awesome because it also means that listening back on previous records you don’t hear songs of yours that you absolutely hate. It’s the cream of the crop — the cream of four crops.

Turning to Side Pony, what’s the shape of that new album compared to your last two studio releases?

Thematically, the hope is that it’s the next step. In that, it’s the next step in the evolution of the band and the four of us as individuals and songwriters. There are hopefully bigger risks being taken, hopefully there are unexpected things, there are stylistic departures. But it’s not a new direction. I think that it’s easy to play a track that relies on disco and think, "Oh, this is going to be a new direction for Lake Street Dive." Never, at any point, did we go into this process and say to ourselves, "Let’s do something new." The thought was more like, "Let’s do something better than last time." Not that last time was bad, just that we always hope to improve upon what we’ve done. That’s the key to longevity, of course.

Genre really does matter in terms of being able to categorize and market a band, but you’ve very proudly remained what I’ve read Bridget describe as "genre-less." Why do you think you’ve been so successful when you’re not necessarily following the formula?

I think the short answer is that we have managed to play successful shows for a really diverse array of audiences over the years and have been able to build a fan base, essentially, wherever we go. We’ve had a lot of luck as openers for bigger bands, and those bigger bands have been a very wide range of artists. We opened for Josh Ritter for a couple of months a few years back, we opened for the Yonder Mountain String Band, we opened for a surf rock band called Los Straitjacketes, which wears luchador masks on stage.

There was a trend: We would be sitting at the merch table after opening for these other bands, and their fans — from one show to the next — consistently we would hear, "Hey that was pretty good." These people that came for something completely different, we somehow managed to keep their attention through our set, sell them merch, and get their names on our email list, and the next time we came to town, they would come back. You can see the music you like in Lake Street Dive. I hope that is what it is, because if not, I don’t really have any other answer.

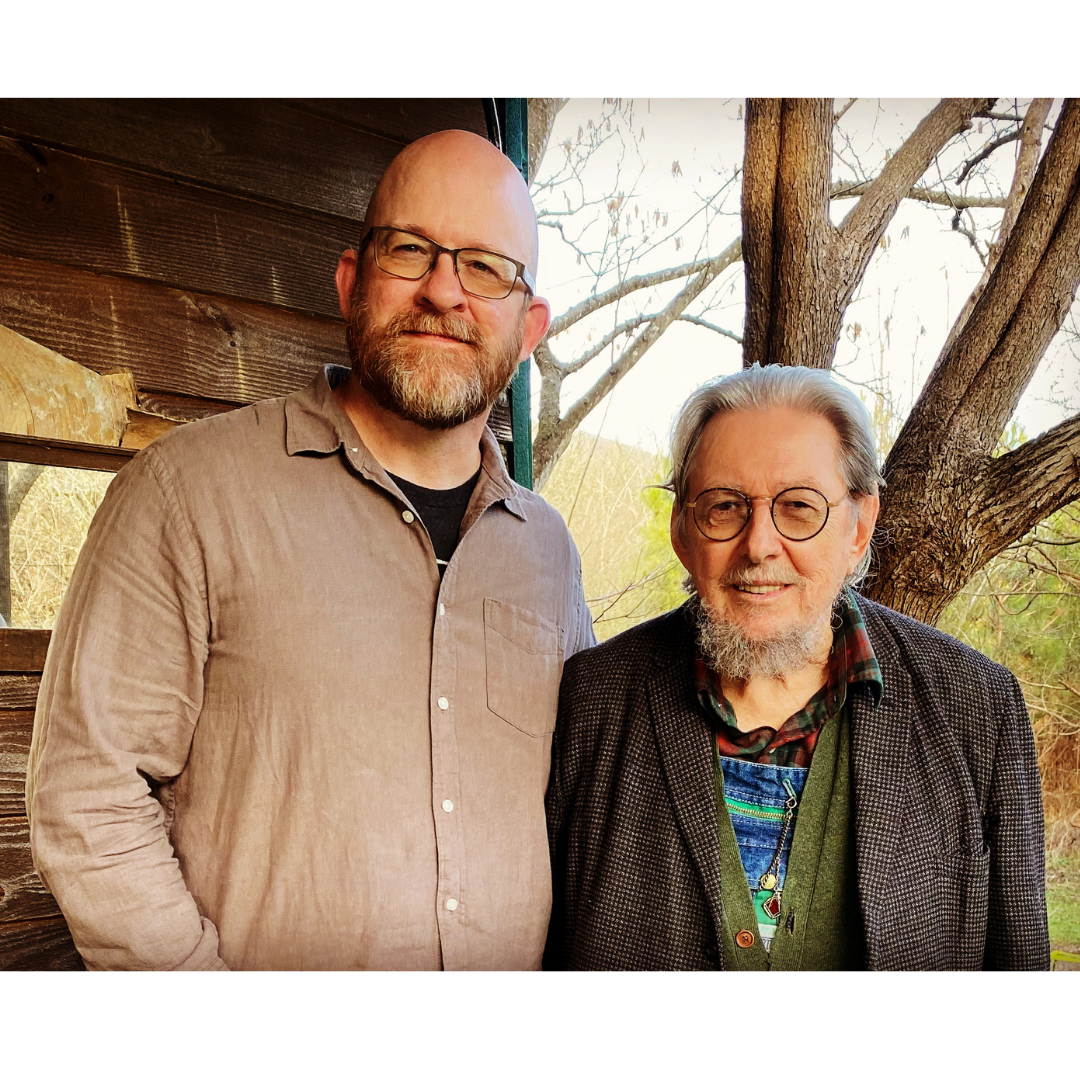

Photos courtesy of the artist