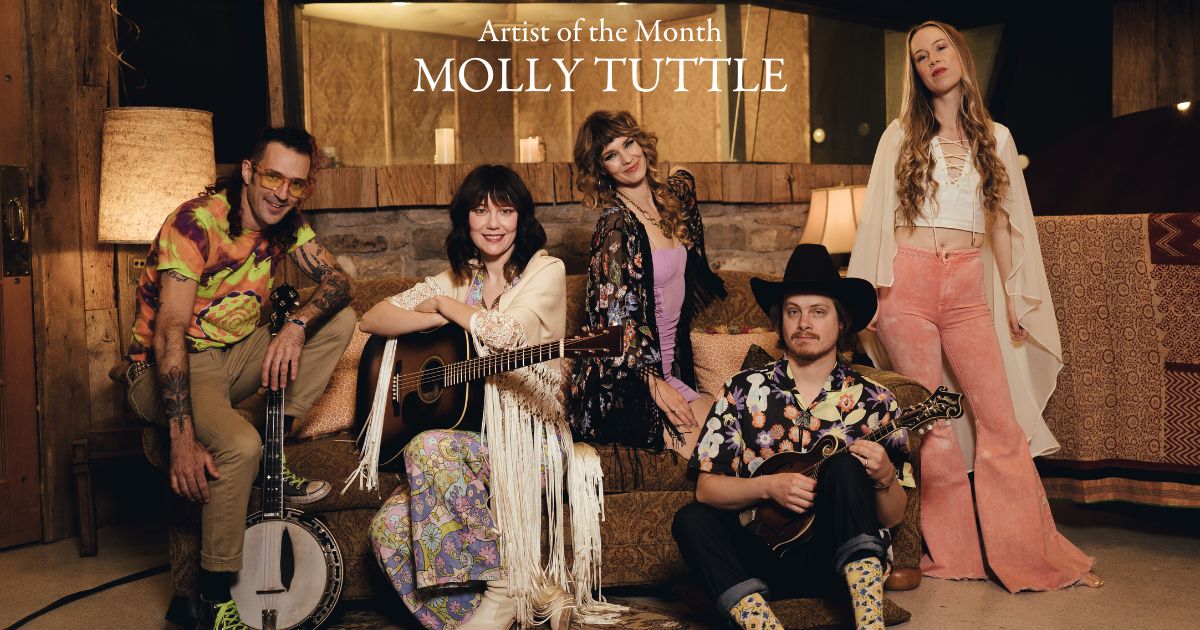

Over the course of her lifelong career in bluegrass, Americana and roots music, we’ve had the pleasure of interviewing and connecting with Grammy Award winner Molly Tuttle on quite a few occasions. When we selected Tuttle and her band, Golden Highway, as our Artist of the Month, we wanted to open a space to discuss her career and music in a fresh light – and we could think of no better context for such a conversation than Basic Folk.

We asked Basic Folk podcast hosts Cindy Howes and Lizzie No – who featured Tuttle on the show once prior, in 2022 – to sit back down with the International Folk Award and Americana Award winner to discuss her brand new album, City of Gold, and to dig deeper into the creative output of this buzzworthy guitar player, songwriter, and business woman.

Watch for the full podcast episode to drop later this month, but for now enjoy these excerpts from Cindy and Lizzie’s conversation with Molly Tuttle.

Cindy Howes: Molly Tuttle, welcome to Basic Folk again. It’s so great to have you back on the podcast.

Molly Tuttle: Thank you so much for having me back. It’s great to be here with you guys.

CH: Before we start our interview, I want to set the tone for our conversation. Molly Tuttle is being highlighted as Bluegrass Situations’ Artist of the Month, which is so awesome. The tone of our interview today is LYLAS. Do you know what LYLAS is?

Lizzie No: It’s spelled L-Y-L-A-S.

MT: LYLAS. Okay. I don’t know that.

LN: What it means is: “Love you like a sister.”

CH: Oh yeah. So we are total LYLAS. This is like a fun trip to the mall. This is like a really fun cruise around the harbor with your gal pals.

MT: Oh my gosh, that’s so fun. Well, it’s perfect because I’m actually in a hotel outside of Missoula. And there’s a strip mall nearby. So shopping has been on my mind today. Great.

CH: We’ll all get mani pedis together.

LN: Yes. French tip.

CH: So, when approaching the writing on City of Gold, you asked yourself, “How do I tell my story through bluegrass?” Which I can relate to, as somebody who’s sort of tried to distance themselves from folk music for a really long time. And now I am fully leaning into it. So, I take [it as] you asking that question of yourself, like “How can I fit my Molly Tuttle-ness into a world that can be rigid, patriarchal, and maybe different from what you stand for.” So how true is that? And how have these songs helped you take control of the bluegrass narrative and tradition?

MT: I think that’s something I’ve always kind of struggled with. I remember when I first started writing songs, I just thought, “I don’t know how to write a bluegrass song.” I can write a song, but they never ended up sounding like bluegrass to me and I just didn’t feel like my story fit into the bluegrass narrative of the songs that I grew up singing.

I always loved songwriters like Hazel Dickens, who wrote bluegrass songs from a woman’s perspective, wrote songs about the struggles that she had as a woman in the music industry and as a working woman, and songs about workers’ rights and things she believed in. I grew up with two really strong role models, Laurie Lewis and Kathy Kallick, out in the Bay Area. I remember early on I would go out to [Kathy Kallick’s] house and she would make me tea and listen to my songs. She always told me that when she was first getting started writing bluegrass songs, she kind of felt the same way as me. Like, maybe her story didn’t belong in the genre. But she met Bill Monroe, and he encouraged her, “Don’t try to write a song that sounds like a song I would have written, write a song from your own perspective.”

So she wrote a song called “Broken Tie” about her parents getting a divorce. She said every time she was at a festival with Bill Monroe, he specifically requested that song. That was an inspiring story to me. But when I started writing songs for Crooked Tree, it was suddenly like a floodgate opened. I think I just found my people to write with, found my groove, and ended up with a collection of songs that kind of told my story, [told] about things I believed in, and [told] my family history and personal experiences. And then other songs that were just, you know, from a woman’s perspective, or from a perspective that I resonate with.

For [City of Gold], it was fun to kind of continue that and also expand it to be songs that I felt like were inspired by my band members, or inspired by experiences we’d had on the road. This felt more like a collective vision in a way.

LN: Okay, let’s talk about Crooked Tree. The title track from your last record was partly inspired by your experience living with alopecia. You’ve said that as a kid you would wear hats and then wigs, and then you learned to talk about your wig. Eventually, you started to get more comfortable going without. Now that you’re touring with Golden Highway a ton, you sometimes take your wig off when you play that song, which is such a powerful moment of joy, courage, and vulnerability. As a performer, I can relate to those moments where you bring a little bit extra of yourself and you share a part of yourself that you might normally keep private. How do you get to that right mood? How do you gauge if the crowd is like the right crowd to share about your alopecia experience?

MT: It’s also based on how I’m feeling. I took off my wig a few times last year. But I didn’t do it as much as maybe I wanted to, or maybe I should have, just because I wasn’t always sure what to say. I’ve had so many experiences of trying to explain alopecia to people and they still think I’m sick or still feel bad for me. And it’s so hard sometimes to put it in words that aren’t going to bring the mood down at the show, you know, I want people to be having a good time. I want it to be this fun, inspiring moment, not a moment where people can go, “I feel so bad for you.”

Recently, I performed and told my whole story [for] a keynote speech at this alopecia conference out in Denver, Colorado. I think that was such an important step for me. Just getting to share my story and reflect on the pain of growing up having this really visible difference, but also like, the joy and why it’s so important to me to share that with others and share the message that it’s okay to be different. It’s okay to be a “Crooked Tree.” This last weekend, we played in Michigan, and I did take off my wig and I felt like I finally nailed what I said and the perfect mood. Everyone was cheering and it was just a moment of celebration. I think I’m gonna just continue doing that more and more, but I find that it’s so helpful for me to check in with the alopecia community and feel that support from other people who know exactly how I feel. That makes me feel confident to share my message with the world and maybe sometimes be like, “I don’t care how it’s received, maybe I’m not sure how it’s gonna be received, but I’m going to do it anyway.” That just comes with time. And I guess I’ve had to grow kind of a thick skin. It used to be a lot harder for me.

CH: The new album, City of Gold, the songs were mostly written by you and your partner Ketch Secor of Old Crow Medicine Show. What is the writing process like with you and Ketch? Like, how do you bring out the best in each other’s writing?

MT: We’re both quite different writers. He’s very fast paced. He throws out ideas and lines. [While I’ll] think it over. I’m kind of more internal. I think about the lines. We balance each other out in a way where I might think a lot about what exactly we are saying, and then he’s good. If I get stuck on something, [he can] kind of keep it moving. But our writing process is always different. It’s nice, because we’re together a lot. So we can write in a lot of different circumstances. Some of the songs we wrote in the car, like on a road trip, just throwing lines back and forth. Maybe he’d be driving, I’d be writing the lines on my phone. Maybe we’re talking about something at home or listening to music and sitting down with instruments, kind of more the conventional way of writing. I find it so hard to fit writing into my life, especially when I’m on tour and I’m on the go so much. [It’s so nice that] we got into a groove with it, where we were just doing it all the time, and it felt more naturally intertwined into my day-to-day life.

LN: The bluegrass community was a huge source of inspiration for you. Of this record, you said, “One of the things I love most about this music is how so much of the audience plays music as well.” And that you hope that people will sing along and maybe play those songs with their friends, almost like we’re all a part of one great big family. Now, how do you walk the line of making a sophisticated, bitchin’ bluegrass record, while keeping it simple enough for others who might not be musical geniuses to play along?

MT: The beauty of bluegrass music is that most of the songs have like three or four chords. You can play them really simple, you can just strum along and play as slow as you want. Beginner bluegrass musicians might go to a jam of people at the same level as them and play these songs in a lot simpler of a way. Then, as you get better and better you can play it faster, you can play more complicated solos, you can really play with the dynamics. There are infinite ways to make the songs more and more complex and sophisticated as you progress in your musical abilities.

On City of Gold, I did kind of stray away from that “three chords and the truth” format a little more than I did on my last record. It was fun, because we were working on these arrangements as a band, which was a lot different process than I’ve ever done before in the studio. I’ve always gone in with my songs and gathered musicians that I don’t normally play with on the road – studio musicians. I have a lot of my bluegrass heroes on the record, and you’re kind of learning the songs and playing them by a chart, but for this album, we really took the time to develop more complicated arrangements and add in new sections that stray away from the key. These songs are a little less accessible to the standard bluegrass jam. But I think there’s still a few that people could learn to play at any level.

• • •

CH: Okay, now we’re going to talk specifically about some of the songs on the new album, City of Gold, starting with the first song, “El Dorado.” Right now I am rewatching Deadwood, so I am super into this song. As a kid, you took a field trip to Coloma, the site of California’s first gold strike and it was the first time you heard about the legendary El Dorado, the City of Gold. In the song you sing, “El Dorado, city of gold, city of fools.” You said, “Just like gold fever, music has always captivated me.” So who are the characters in the song – like gold rush Kate from the Golden State – and how do you connect with these fools?

MT: I wrote the song with Ketch and I don’t know [exactly] how it came about… [But I told him,] when I was a kid, every school would send the kids off to gold country. You’d go to different places. The person who taught my class how to pan for gold, for some reason I have like a very vivid memory of him. He had this gold nugget on a chain around his neck and he showed us how to pan for gold. He was like, “You might find a flake of gold, but if you find an actual nugget of gold, we’re not gonna let you keep that, you have to give it back to us.” [Laughs] I remember being like, I really want to find like a nugget of gold and just squirrel it away and not tell this guy about it. So that kind of stuck with me.

CH: Literally every kid in your class thought that!

MT: Yeah! Like, we’re gonna strike it rich at this goldmine!

We were kind of doing some research on Coloma and found that it’s in El Dorado County. That seemed like a good place to start with a song just inspired by that character, but also thinking about all these characters who came together and we’re all trying to strike it rich. I feel like that is such a theme in our society. You know, we have these like little, mini gold rushes – everyone being like, “This is the next big thing. We’re all going to make so much money off of this.” But for me, I didn’t get into music thinking this is gonna make me rich, but it is something I’ve chased after for many years now.

CH: What do you think is the current gold rush? Is it dispensaries? Vape stores?

MT: The thing that just popped into my head, it’s a couple years old, maybe like a year past its prime, is crypto currency. I think I don’t know where that stands. But I think we’re a little bit past that.

• • •

LN: The second track on this album is “Where Did All the Wild Things Go?” Which is a song about gentrification’s corrosive effect on the character of once-vibrant neighborhoods nationwide – which I can very much relate to living in Brooklyn. I’d love to hear about your neighborhood where you live now. Is there a specific tradition or neighborhood institution or restaurant or store that is so special about your neighborhood? That you’re passionate about preserving? And how are you and your neighbors trying to keep your neighborhood weird and wild?

MT: Well, my neighborhood is East Nashville, and before I got there, it was totally different. It’s just in constant flux. It really changed so much when we had the tornado hit [in 2020] that took out tons of the local businesses that never returned. A lot of people moved out. The pandemic just kind of sped all of that up. Coming out of lockdown I was like, “Whoa, this is so different. Like, where do I even live anymore?”

I don’t really know how to answer how I’m trying to preserve it. I feel like I’m living in a different city every time I come back from tour, basically. Nashville’s always changing, just constantly growing, so many businesses are moving here. I do feel like there’s this constant sense of everyone missing the old Nashville. I don’t think that I was even around for the like “old Nashville” as many people who grew up in the city know it. So maybe I’m part of the problem in a way, really. I moved there just eight years ago…

• • •

CH: The next thing we want to talk about is “San Joaquin,” a new, old-style railroad song. There’s such a romance surrounding trains in song. You’ve always loved singing about trains. There is that long tradition of trains and folk songs. What do you think it is about trains that have captured artists’ hearts since they’ve been around?

MT: I think as artists, especially as musicians, we kind of have this roving spirit, where we want to see the world, we want to travel. I feel like a lot of musicians, myself included, we romanticize trains as this early way of getting across the country. And still, you’ll see musicians from time to time doing a train tour. Of course you have buskers who might hop on a train across the country and play all over the place. Now, I’ve never done that, but I think it’s just this thing that’s romanticized, especially by musicians. I’ve always loved singing [train songs]. There’s so many bluegrass train songs, but I didn’t know a specifically California bluegrass train song, so I felt like it was time to write one.

CH: What’s your favorite train song?

MT: That’s such a good question. The first one that popped into my head was Larry Sparks’ song, “I’d Like To Be A Train.” He doesn’t just want to ride a train. He wants to be a train.

• • •

CH: The song “Next Rodeo” you say, “…Reflects the miles I’ve put in with my band, Golden Highway, which has clocked in well over 100 shows.” That’s in the press release, so it’s probably 200+ shows at this point, and we’ll give a shout out to Bronwyn Keith-Hynes. Let me know if I’m mispronouncing anyone’s name–

MT: We have so many nicknames for Bronwyn in the band. We saw a YouTube comment on one of our videos where I introduce her and someone said, “What’s the fiddle player’s name? I couldn’t catch that.” Someone wrote “Ron Winky Pies.” We often call her Ron Winky Pies.

CH: Yes, that sounds right. Well, she is a hell of a fiddler. Also Dominick Leslie on the mandolin, Shelby Means on bass, and Kyle Tuttle, who is playing banjo. Can you talk about the ease and connection you feel with Golden Highway? What’s the feeling that you get when you’re on stage – and, when did it start gelling for everyone?

MT: After I made Crooked Tree, first I started thinking about who I wanted to take the songs on the road with. On the record I had the band name Golden Highway, but I didn’t actually have a band yet, so it’s kind of funny. I did it in reverse a little bit.

Dominick played on the whole record. I called him and I was like, “Hey, do you want to play with me next year?” And he said yes. So I had one band member. I was just trying to fill in the rest of the band thinking like, “Who’s gonna bring the most personality to this project? Who’s gonna bring a unique voice?” The whole record was all about being who you are, [about] individuality. I wanted to choose people who I felt like their personalities really shine through – and their music and their playing and their stage presence.

I got my dream band. We’ve all been friends in one way or another for like the past decade, so it was a cool experience. I’ve never had that before where I have this band in my head, I imagine the people playing together, and then it happens and it’s better than I could have imagined. It felt really cool. In the past I’ve had wonderful bandmates, but it’s never been this kind of brainchild where I’m trying to concoct my dream bluegrass band that will have this unique personality to it.

We all got together and everyone already knew each other and already played together in different configurations just through the bluegrass scene over the years. It all kind of started gelling really quickly. Our first couple shows we’re just kind of like, “Wow, this is something special!”

• • •

CH: We do want to ask a question about Jerry Douglas, who co-produced the record with you and is the master of the Dobro. How has your relationship with him as a producer shaped how you think about your own recordings?

MT: On this record, especially on “Stranger Things,” I just felt like I needed to hear him play on it. We had this funny thing we’d say in the studio, “Make us AKUS” – make us Alison Krauss and Union Station – cause they’re like our heroes. [Laughs]

When we got to that song we’re like, “We need that iconic Jerry Douglas dobro part.” It’s such a spooky song and he just knows how to accompany a song [like that] so well and that’s part of why I felt like he was the dream producer. He understands the musicianship side of things. He’s such a master of his instrument, but then he also has this deep connection to songs and vocalists and just knows exactly what to play behind the vocal.

That’s something I really kind of leaned on him for, just getting the best performance out of everyone, instrumentally. He has just the greatest ear. He hears a pitchy note here or like a wrong note there and really pushes everyone to do their best performance, but then he also has this side of him that’s extremely tasteful and he knows how to get behind a song and not overpower it.

LN: I want to talk about “Down Home Dispensary,” which is such a fun song. I’m fascinated by the way you’ve framed this issue, which is very hot in the news… legalizing marijuana. The way it’s framed in “Down Home Dispensary” is like a very fun political pitch about how Southern culture can evolve and is evolving. Why did you feel it was really important to frame this as a “Down Home Dispensary?” And do you notice an evolution in the way that Southerners and your audiences, more broadly, are relating to marijuana use?

MT: I think like the South is still the holdout. It’s not legal in most places in the South, but I feel like it’s become almost a bipartisan issue, where people are getting behind it. We play it and we’ve been playing it live and people are cheering no matter who they are. They’re like cheering for the “Down Home Dispensary,” because it’s this thing that’s become normalized in our society, but it still is technically not legal. That was one that Ketch and I originally wrote to be an Old Crow [Medicine Show] song and then they didn’t cut it. It’s so much fun!

CH: It’s sort of like a book end to “Big Backyard.” The world can be your down home dispensary, your backyard. You can make home and freedom anywhere.

MT: I thought it was like a funny angle to to go about it. You’re talking to a politician and just being like, you should really do this, because you’re gonna make a lot of money like this is in your best interest.

LN: How has living and working in Tennessee changed how you see your responsibilities as a feminist artist?

MT: I’m confronted with things in Tennessee that I never imagined would happen. Where I live, abortion is not legal in Tennessee at all, it was one of the first states to basically ban it for any reason.

That was really like a dark moment in our history as a country to just be going backwards completely. It’s something that I’ve feared since I was a teenage girl, like, what if this got taken away? And what if I couldn’t make decisions for my body? I can’t [access this healthcare] in the state where I live, I could maybe travel somewhere else if needed, but who knows if [someone else] could. They could make it more and more impossible to have access to this. It just breaks my heart for all the people who now don’t have that choice and don’t have the privilege of being able to go somewhere where they can get this health service.

[When writing “Goodbye Mary”] I was thinking about a story my mom told me growing up of my grandmother, whose name was Mary. She had a friend who was in an abusive relationship and she wanted to leave this relationship, but she ended up getting pregnant. So my grandmother and her friend, she would push her friend down the stairs, they would try anything to get rid of the baby. It’s a really, really dark story. But it’s somewhere that we’re going again, as a nation. When we were writing it, we were talking about my grandmother. That’s not something that happened to my grandmother personally, but it’s something that her generation had to deal with.

LN: I think it’s so important to link abortion access to women’s experiences of intimate partner violence. A lot of people who claim to be pro-life don’t want to admit that access to abortion is also access to freedom and the ability to leave an abusive situation. It’s just one more way of actually having freedom in your own body. That’s a really powerful story. It’s just so important, I think, for musicians to be talking about this issue, especially those of us that live in Nashville or are working in country and folk and bluegrass.

MT: It’s really scary to talk about, I was so scared to put that song on my record. Jerry was the one who was like, “We have to.” It was his favorite song. He was like, “If we’re gonna record one song, it needs to be this one.” And I was like, “I’m scared.”

This issue is one I care about so deeply. And it’s one of the most important social issues to me. But it’s also like, you get kind of the most backlash for it.

LN: Have you played this live yet?

MT: We haven’t, no. We’ve worked it up. And once the record is out, I think we will start playing it. But we haven’t tried it live yet.

LN: You got this.

MT: Yeah, totally. Thank you.

LN: Thank you. Thank you for this telling this story. I think that the bluegrass community needs to hear it and the world needs to hear it. I think it’s really important.

• • •

(Editor’s Note: This conversation has been abridged and lightly edited for flow and grammar. Cindy Howes’ and Lizzie No’s full Basic Folk conversation featuring Molly Tuttle will be available next week on BGS – or wherever you get podcasts.)

Photo Credit: Chelsea Rochelle