In recognition of Black History Month, we have compiled these 12 features from the Bluegrass Situation archives to reexamine the breadth and sheer talent that Black artists are bringing to the roots music community. For additional stories, and to hear much, much more music, check out our Black Voices page on BGS.

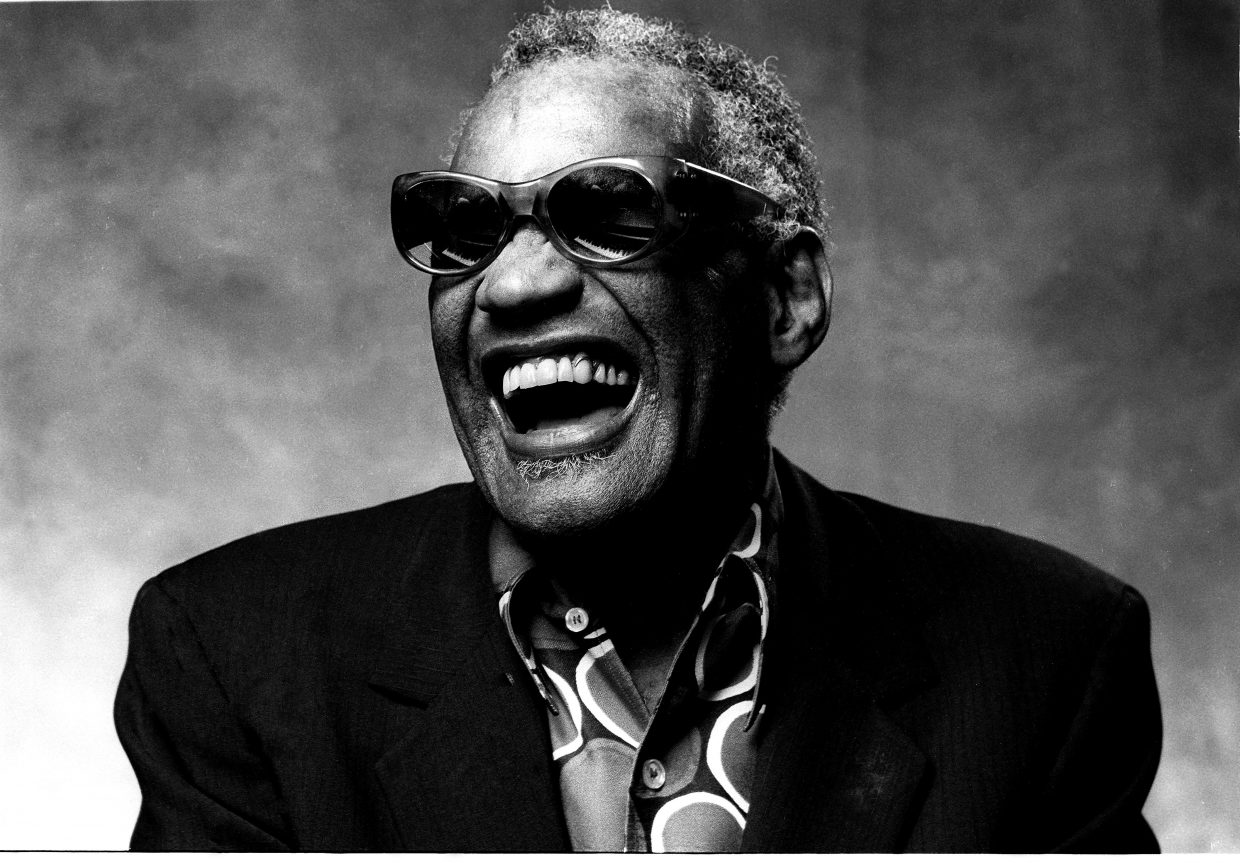

Ray Charles

The musical and cultural impact of Ray Charles is extraordinary and spans the pantheon of American popular music. He was an outstanding multi-instrumentalist (though best known for piano and alto sax), vocalist, bandleader, songwriter and composer in the non-lyrical sense. His innovations include helping craft and popularize the secularization of gospel music, now otherwise known as soul, and bringing new attention and expanded audiences to country music, which was the earliest idiom he loved and played before blues, jazz, R&B, or soul.

Though his earliest material was heavily influenced by Charles Brown and Nat “King” Cole, Charles (full name Ray Charles Robinson) quickly developed a highly stylized, immediately recognizable singing and playing approach. He became an expressive, evocative vocalist, one of the finest interpretative singers of all time, and a skilled improviser as an instrumentalist, able to deliver intense and memorable melodic statements or energetic solos while heading either small combos or large bands. Read more.

Robert Finley

Depending on how much attention one pays to labels, singer-songwriter Robert Finley could accurately be called both a blues and soul vocalist, even though he’s also performed plenty of gospel, and has a passionate faith that is often reflected in comments about his unlikely emergence as a national figure in his 60s.

“You can’t call it anything except the hand of God a lot of what’s happened in my life,” Finley tells BGS. “For me to be recording and performing now, to have met and established a friendship with a young white guy like Dan (the Black Keys’ Dan Auerbach), and to be in the studio now recording and singing these songs when that’s what I’ve always wanted to do all my life, well it’s just God’s hand in my life.” Read more.

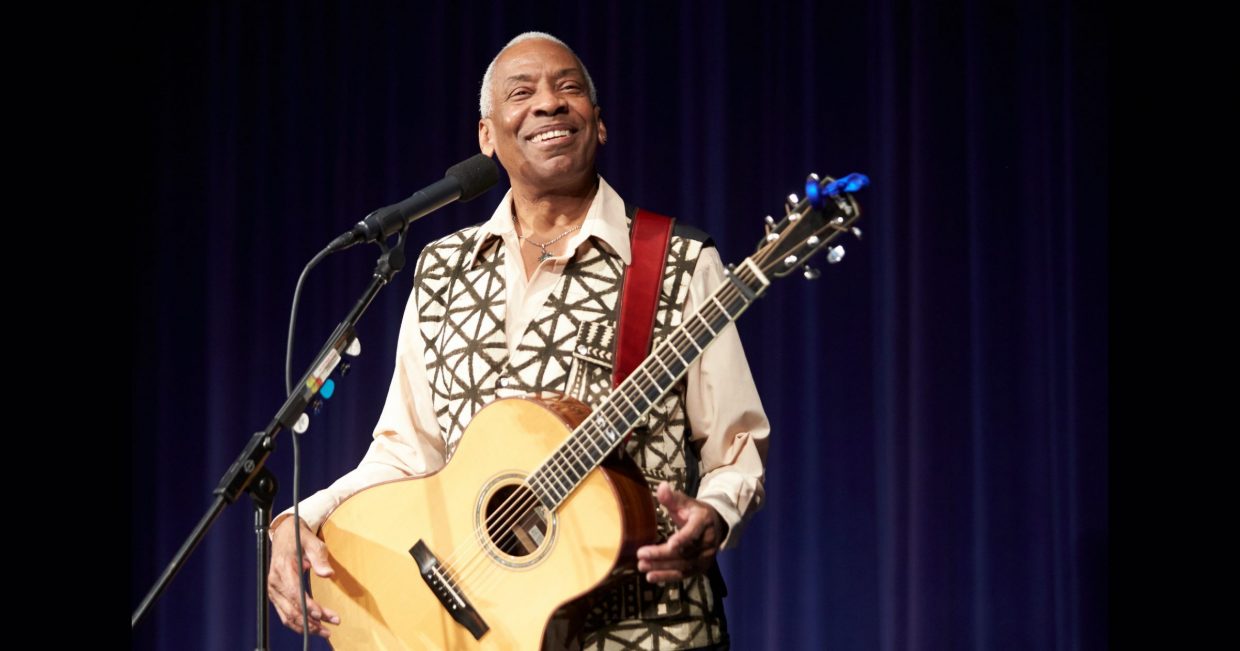

Reggie Harris

The joy and hope evident in Reggie Harris’ 2021 release, On Solid Ground, stem from a rooted sense of perseverance and from his intentional decision to face each and every moment, in the moment, and to find hope within each. It’s why such heavy topics don’t feel gargantuan or burdensome as they make appearances and anchor songs on the album. Harris, watching the social, political, and racial reckonings that bubbled onto the sidewalks and streets of every city in America over the course of the last year, didn’t sit down or give up in the face of the unclimbable summit of translating that reckoning into song.

Instead, Harris draws upon the wisdom, insight, and hope given to him by his own elders and communities throughout On Solid Ground. In choosing to keep himself open in each moment, Harris found himself receiving inspiration, nuggets of ideas and stories, glimpses of songs and arrangements in so many of those moments, simply because he was there, with a still heart and still soul, to receive them. Read more.

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram

Christone “Kingfish” Ingram seemed to come out of nowhere with his 2019 Alligator Records debut, Kingfish. At 20 years old, the native of Clarksdale, Mississippi, emerged as a fully-formed guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter and was quickly hailed as a defining blues voice of his generation. Since then, he’s toured the nation, performed with acts ranging from alt-rockers Vampire Weekend to Americana star Jason Isbell to blues godfather Buddy Guy.

In the midst of all this success, just as his career was taking off amidst over a year of non-stop touring, he lost his mother, Princess Pride Ingram, a devastating blow that the young man had to overcome. All of this life experience is reflected on Ingram’s second album, 662, named after the area code for his North Mississippi home. Read more.

Amythyst Kiah

When Amythyst Kiah was a teenager in the suburbs of Chattanooga, Tennessee, she wanted to be “the guitar-playing version of Tori Amos.” Locked away in her room with her headphones pulled over her ears, pouring over liner notes and listening intently for every nuance in her favorite records, she found solace in the way Amos told her darkest secrets in her songs and how she turned that vulnerability into something like a superpower. It made her feel less alone, especially as a young, closeted Black girl in a largely white suburb. Tori Amos helped her survive adolescence.

Kiah didn’t grow up to become any version of her hero. Instead, she simply became herself. Her new solo album, Wary + Strange, ingeniously mixes blues and folk with alternative and indie rock, devising a vivid palette to soundtrack her own songs that tell dark secrets. It’s one of the most bracing albums of the year, grappling with matters both personal (her mother’s suicide) and public (the struggles of Black Americans). “Now, when I’m in my mid-thirties,” says Kiah, “it’s amazing to make a vulnerable record and then have people at my shows tell me that my music helped them heal, helped them get through some hard times. To have someone connect with my music is really powerful.” Read more.

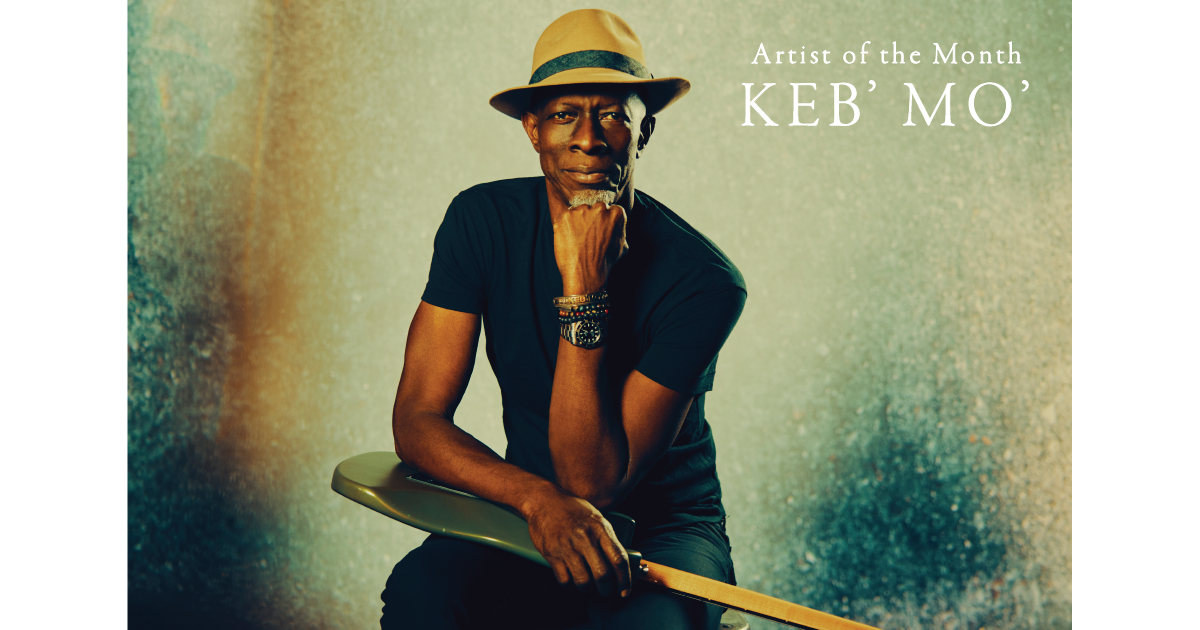

Keb’ Mo’

Keb’ Mo’ enjoyed a career milestone as he received a Lifetime Achievement in Performance Award from the Americana Music Association in 2021. Presented at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, the award joins a list of distinctions that include five Grammys and 14 Blues Foundation Awards. But in typically understated fashion, Mo’ (a.k.a. Kevin Moore) downplayed the latest honor during his Artist of the Month interview with the Bluegrass Situation.

“Well, for me I guess it represents the fact I’m getting old,” he said with a laugh. “But sure, you are honored whenever you get that kind of recognition from your peers. But I’ve still got a lot that I want to do and I’m still looking ahead.” A huge indication of that is his outstanding new LP, Good to Be. It is both a tribute to his background growing up in Compton, California, and a celebration of some 11 years in his current hometown, Nashville. Read more.

Buffalo Nichols

As the first solo blues artist signed to Fat Possum Records in 20 years, Buffalo Nichols faces high expectations. But on his self-titled debut, the musician (whose given name is Carl Nichols) more than meets them, stitching Black history and musical traditions with current events and experiences to craft the sonic equivalent of a quilt. And the story it tells is an important one.

Nichols was born in Houston and raised in Milwaukee, but when he got the urge to roam and the money to do it, he took off, immersing himself in creative scenes across Europe and West Africa. Although he’s been based in Austin since the fall of 2020, Nichols channels the Delta, North Mississippi and Chicago through his nimble fingers or resonator slide while wrapping his warm voice around words that cut to the core of oppression, and the many forms of heartbreak it causes. Read more.

Chris Pierce

Chris Pierce has cultivated a significant following in the Los Angeles area and beyond, usually writing soulful and emotional songs that have populated fifteen years’ worth of albums and appeared in TV shows like This Is Us. But in 2020, accompanied by little more than his 1949 Gibson J-45 (“Blondie”) or his 1973 Martin D-18 (“Doriella”), the California native recorded the album American Silence with a mission of social activism against racial disparities.

Pierce gained a love of language from his mother, an English teacher who taught at-risk youth. She introduced him to the lyrical writings of Shel Silverstein and Dr. Seuss, as well as essential writers like Langston Hughes and Walt Whitman. The economy of words in all of those authors is immediately evident in original compositions like “American Silence” and “It’s Been Burning for a While,” where Pierce gets his point across directly, and with power. His convictions are never more optimistically presented than in the album’s closing anthem, “Young, Black and Beautiful,” which details the experience of maturing from a cute little kid to a perceived threat. Read more.

Allison Russell

Within the songs of her new album Outside Child, Allison Russell delves deeply into the extreme trauma she experienced in her youth spent in Montreal both as a mechanism for personal relief, but also in the hopes that it might reach people with similar experiences.

“The writing process was having to delve deeply into the most painful parts of my past and childhood and history,” she says. “I experienced severe childhood abuse, sexual, physical, mental, and psychological. In many ways, I think the psychological is the toughest part to unpack and defang. I don’t know that I am ever going to be entirely free of that and the process of dealing with that. What was very beautiful about this to me is that I didn’t have to go on that fearsome journey alone. My partner J.T. [Nero] was with me every step of the way. He co-wrote many of the songs on this record with me. He scraped me up off the floor when I was in the depths of it.” Read more.

Tray Wellington

Banjo player Tray Wellington was everywhere to be found during the 2021 IBMA World of Bluegrass — performing, hosting the Momentum Awards luncheon, and playing a main stage set at the Red Hat Amphitheater. This is remarkable because if you had looked for Wellington at IBMA just a few short years ago, you might not have run into him except on the youth stage or in the halls, jamming.

Catapulted by his prior work with the talented young band Cane Mill Road, his studies at East Tennessee State University’s bluegrass program, and a stable of accomplished and connected mentors and peers, Wellington went from a newbie to a seasoned veteran faster than a global pandemic could subside — and during it. Efforts for better and more accurate representation in bluegrass have contributed to his momentum (no pun intended), but above all, his talent and his envelope-pushing approach to the five-string banjo are the root causes of his mounting and well-deserved notoriety. Read more.

Yasmin Williams

Guitarists spend lifetimes — often gleefully, sometimes manically, or at times frustratingly — finessing techniques, especially with their picking hand. Entire careers can be made or broken by the idiosyncrasies of one picker’s striking and sounding strings. Fingerstyle guitarist and composer Yasmin Williams has mastered myriad forms of right-hand styles, each complicated enough for multiple lifetimes’ worth of study. But she doesn’t merely alternate techniques between pieces; to a transcendentally perplexing degree she effortlessly alternates her entire picking hand approach mid-song.

On her 2021 release, Urban Driftwood, a collection of thoughtful, dynamic, and engaging instrumentals written for fingerstyle guitar and harp guitar, Williams makes many of these technique-swaps while the compositions charge forward, each one earning tailor-made right-hand approaches. As a result, the songs don’t feel encumbered when Williams, mid-melody, goes from right hand fingerstyle to bowing her strings with a cello bow, or plunking out notes on a kalimba taped to her guitar’s face, now positioned laying across her lap. She utilizes hand percussion and tap shoes to fill out arrangements, interposing Afro-descended instruments from around the world into her compositions, and she picks up, puts down, and readjusts her stable of musical tools in real time — as a foley sound effect artist, prop master, or choreographer might. Read more.

Yola

Speaking to Yola over Zoom is way more fun than a video call has any right to be. From the time she dials in from the UK, she’s ready to chat. Good thing, because there’s a lot to talk about. About a week earlier, she picked up two Grammy nominations in the American Roots Music category of Best American Roots Song (“Diamond Studded Shoes”) and Best Americana Album (Stand For Myself), and she’s clearly still exhilarated by it.

“It’s very hard for it to even land because it feels really super surreal,” she says. “I don’t know how else to describe it. I’m endlessly grateful to the work that everyone puts in to get me to this point, and honestly, the faith that people have to let me lead at all. I wasn’t always in positions like that, ones that would let me lead.”

She’s speaking of a different kind of leadership style than, say, former British Prime Minister Theresa May, whose sparkly footwear worn during a speech about childhood poverty led to the idea of writing “Diamond Studded Shoes.” Although it does have a feel-good groove, you can’t miss its message of inequality. “And that’s why we gots to fight,” she sings. Read more.

Photo Credit: Norman Seff (Ray Charles); Alysse Gafkjen (Robert Finley); Courtesy of Reggie Harris (Reggie Harris); Justin Hardiman (Christone “Kingfish” Ingram); Sandlin Gaither (Amythyst Kiah); Jeremy Cowart (Keb’ Mo’); Merrick Ales (Buffalo Nichols); Mathieu Bitton (Chris Pierce); Laura E. Partain (Allison Russell); Mountain Home Music Company (Tray Wellington); Kim Atkins Photography (Yasmin Williams); Joseph Ross Smith (Yola)