There are two types of people in this world: those who love Nashville and those who prefer Memphis. I fall into the latter. Located on the banks of the Mississippi River, Memphis is one of the South’s most diverse cities. The music history is rich. Jazz and blues incubated on Beale Street. Stax Records brought the soul. The trail of tears crossed the Mississippi. With so much to see and do, it’s important to go in with a plan and some sights in mind.

Getting There

Unless you’re coming from nearby, the most obvious choice would be airplane. Memphis has a major international airport, so you should have no problem getting a flight. If you are coming from down South, take Highway 61. It might take a bit longer, but you’ll come up the blues trail. Be sure to make a pit stop in Clarksdale, MS. It’s full of juke joints and good eats. You’ll pass the crossroads where Robert Johnson allegedly sold his soul … It’s now a parking lot.

Accommodations

The Peabody Ducks. Photo credit: Roger Schultz via Foter.com / CC BY.

Memphis is not an expensive city to visit and there are ample places to stay. I stayed at my friend Tim’s house, but that’s not an option for you: He’s a private person and doesn’t take kindly to unannounced strangers.

A good place to start on a moderate budget is downtown. Most of the hotels have decent prices and are also close to all the sights. If money is not a problem, check out the Peabody Hotel. It is a National Historic Hotel and famous for its ducks. The penthouse is home to a family of ducks. Every morning at 8 am, they take the elevator to the lobby. They march to the central fountain and then swim for the rest of the day. At exactly 5 pm each night, they take the elevator back upstairs. It’s been happening for countless generations. A duck walk of fame surrounds the building. Of course, the ducks aren’t the only reason it is listed as a National Historic Hotel. The Peabody is beautiful and emanates old school glamour.

If you are the adventurous type, check out the Big Cypress Lodge at the Bass Pro Shops at the Pyramid. I know, it sounds bonkers. Bass bought the Pyramid that formerly housed the Memphis Grizzlies. They retrofitted it as a massive retail store and hotel. It is amazing. They spared no expense. The closest comparison is Disneyland’s Splash Mountain. There are water features and catfish and dioramas. An enormous faux cypress tree reaches the upper decks of the pyramid. It’s worth a visit, even if you decide on a more practical sleeping arrangement.

Food

Photo courtesy of Central BBQ.

Though famous for its barbecue, Memphis has wonderful food, all the way around. But, playing to its strengths, Central BBQ is a good spot to try out some different styles. Be warned: It’s popular and it gets crowded. Don’t be afraid of their hot barbecue sauce. It wasn’t very spicy. The mustard and vinegar sauces are worth a dip or two. Be sure to check out the great Mississippi Blues Map mural in the backroom.

How about a bit of soul food for brunch? Check out Alcenia’s. For $12.95, you can consume a week’s worth of calories. I had the sausage omelet with fried green tomatoes, a biscuit, potatoes, and coffee. I still had at least one more side choice. All of their food is good. The chicken and waffles are top notch. You’ll also get a kiss on the cheek if Miss BJ, the proprietor, is there. Plan on spending some time at this joint. It isn’t fast food, but it is well worth the wait. Don’t hold it against them that Guy Fieri recommended them. I know he’s a divisive figure, but he’s right about Alcenia’s.

Soul Fish Café was my favorite restaurant this time around. The blackened catfish is absolutely phenomenal. (The fried catfish was also delicious.) I can’t recommend the Soul Fish Café enough. The tables fill up fast, but there’s usually room at the counter. Highly recommended.

In short, I would be enormous if I lived in Memphis.

Drink

Beale Street. Photo credit: charley1965 via Foter.com / CC BY-SA.

If you’re going to Memphis as a tourist, you need to do some touristy things. One of those things is getting drunk on Beale Street — the Bourbon Street of Memphis. Lined with bars, Beale Street is where you’ll find dueling pianos and Stax cover bands. There’s Almost Elton, an Elton John cover artist, and a gazillion blues groups. You can drink in the street, so it’s a good time and it’s probably not somewhere the locals want to hang, but it’s worth visiting while on vacation.

The Cooper-Young neighborhood is another great area for drinks. The Slider Inn is a popular joint. There’s also Young Avenue Deli, which has pool tables and airs the games. Don’t worry if you don’t like sports, the games are muted. Another Cooper-Young neighborhood joint is the Celtic Crossing. On the weekends, they have live Celtic music, often accompanied by clogging.

Best of all, beers are cheap in Memphis. You won’t break the bank with a wild night on the town.

Coffee

Photo courtesy of Café Keough.

Visit Coffeehouse Row. (Nobody in Memphis calls it this, but I think it has a nice ring.) On the way to Cooper-Young, you’ll drive down Cooper Street. You have three different, but good, coffee choices. The first is Muddy’s Bake Shop. This is a cutesy place. You can get cupcakes here. If it were an online retailer, it would be Etsy. Next, you have Other Lands. It’s a bit grittier. They sell beer. If it were an online retailer, it would be Craigslist. Your final choice is Tart. It’s the artsy coffee house. They have a huge outdoor patio that’s great for smoking cigarettes and getting deep. If it were an online retailer, it would be Ziibra. But Café Keough is my favorite coffee shop. It’s downtown and one of the only places with bagels. The place is huge and has a comfortable atmosphere. They also have great t-shirts.

Live Music

Boogie on Beale Street. Photo credit: Heath Cajandig via Foter.com / CC BY.

Hi Tone is one of the best rock ‘n' roll venues in America. We caught a great show while in town — local band the Dead Soldiers were back in town after a long tour. They brought the house down. There were sing-alongs and inside jokes, as drunk people fell off their chairs waving their hands in the air. (It was like they just didn’t care.) There was a lot of love in that room, and it was a pleasure to bear witness. Also, the beers were cheap. I loved it.

Wild Bills is the best blues joint in town. It’s a bit isolated, but they have some great acts. They also serve 40s. Be warned that the music doesn’t start until 11 pm.

If you make it to Beale Street, you’re going to catch a lot of live music. Every storefront offers up something new — traditional jazz, blues, rock ‘n' roll, and soul. The history of Memphis music is proudly displayed seven nights a week on Beale Street. The Southern Folklore Center also puts on some great daytime concerts. Located downtown, they curate an excellent roster that ranges from gospel to blues and everything in-between.

Local Flavor

Graceland living room. Photo credit: Rob Shenk via Foter.com / CC BY-SA.

Memphis has four must-see destinations. You need to go to Graceland. Don’t worry about the plane tour and all the add-ons. They pile up quick. Just go and see the mansion. It’s $36, and well worth it. It comes with a guided iPad tour that is narrated by John Stamos. (Yes, Uncle Jesse from Full House.) The tour is informative and Stamos’s voice sounds a bit like George Clooney, which I had never noticed. The Jungle Room is one of the coolest living rooms ever. The Pool Room is lined in fabric and feels like a 1970s opium den. Elvis didn’t care what was cool. He liked what he liked and the results are a one of a kind home.

Next, you have to visit Sun Studio. So many iconic records were recorded there. It’s where Elvis and Johnny Cash got their start. Howling Wolf cut some amazing sides at Sun before heading up to Chicago. To stand where so many greats have stood before is a powerful feeling.

The Lorraine Hotel, now the National Civil Rights Museum. Photo credit: Andy Miller.

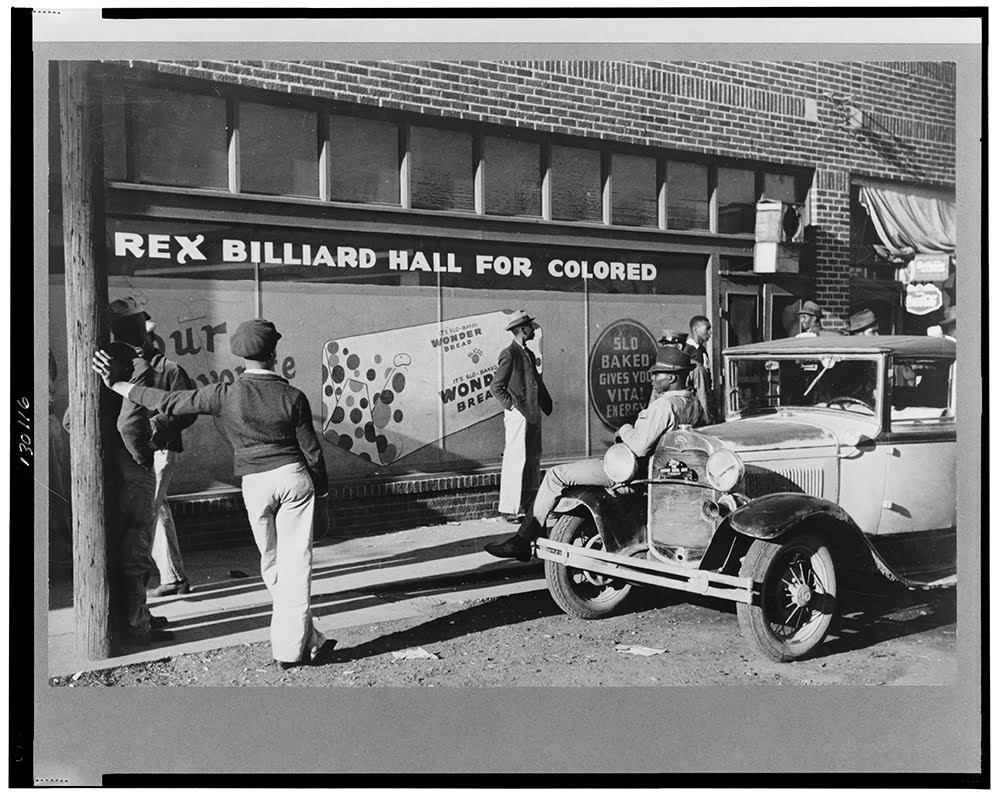

Any Memphis trip is incomplete without a visit to the Lorraine Hotel. This is where Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was shot. It’s now the National Civil Rights Museum. It’s heavy. And it will depress you. That being said, it is important to remember our past mistakes in order to learn from them, especially in today’s extreme world.

Finally, you need to visit the Stax Records Home of American Soul Museum. Isaac Hayes's gold-plated Cadillac is on display and Otis Redding cut his classics in those same halls. If you were ever on the fence between Motown and Stax, you will leave with two feet in Stax’s backyard.

Lede photo credit: BlankBlankBlank via Foter.com / CC BY.