“I want every single person in the world to be a Guy Clark fan,” says Tamara Saviano. “When people ask me why I did the tribute album and when people ask me why I did the book and when people ask me why I did the movie, that’s my response. I want everybody on the planet to go down a Guy Clark rabbit hole. Go listen to the music. That’s what I care about.”

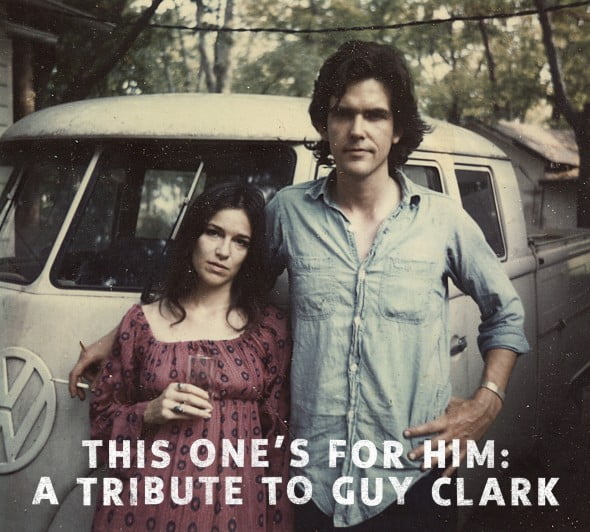

It may sound like a lofty goal, but Saviano is making a lot of headway. She has spent more than a decade making sure people hear songs like “L.A. Freeway,” “The Randall Knife,” and “My Favorite Picture of You.” In 2012, after years working as his publicist, she executive-produced the double-album tribute to the Texas singer-songwriter, This One’s for Him, featuring covers by Willie Nelson, Lyle Lovett, Hayes Carll, and Patty Griffin, among many others.

Five years later she published her exhaustive and affectionate biography, Without Getting Killed or Caught, which follows his life from Monahans, Texas, to Nashville, from his early years as a struggling songwriter to his final days as a foundational figure in Americana. Lovingly written and sharply observed even as it affectionately portrays him as a “curmudgeonly old dude,” it’s one of the finest music biographies of the last decade and will finally get a paperback release next month, with a new foreword by Robert Earl Keen.

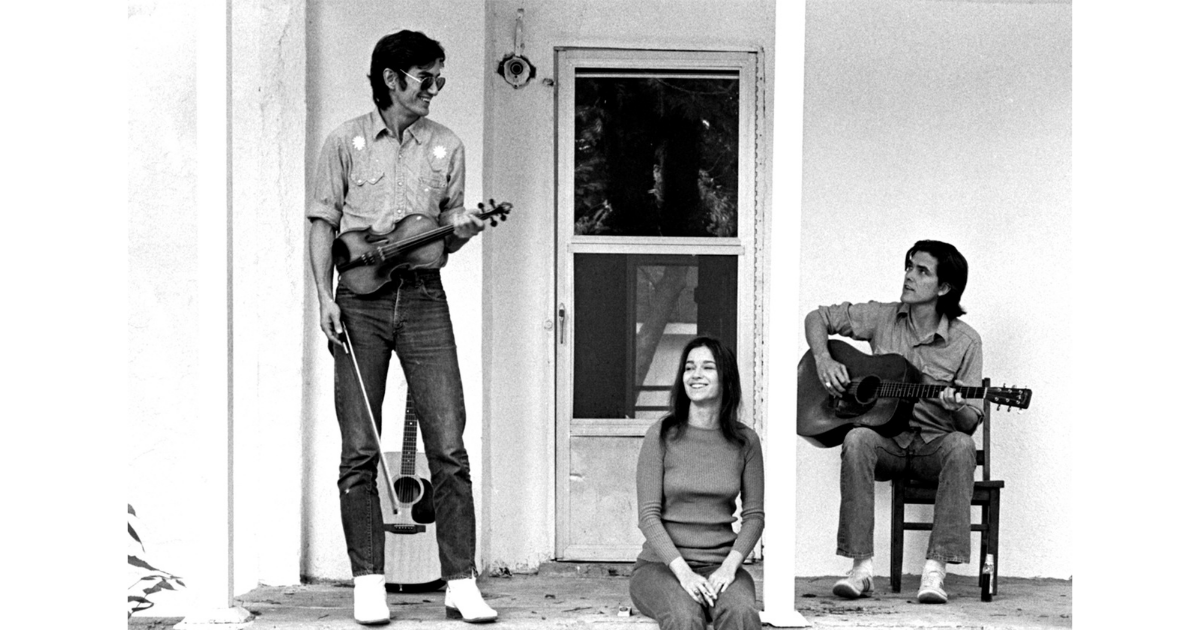

And now comes Without Getting Killed or Caught, the documentary Saviano co-wrote with Bart Knaggs and co-directed with her husband, Paul Whitfield. While the book focused squarely on Guy, the film (which is available for streaming) examines his marriage to Susanna Clark, his friendship with Townes Van Zandt, and how those relationships overlapped over the decades. They all lived together in the 1970s and Susanna often described Townes as her soulmate, but the documentary never resorts to sensationalistic details or soap opera storylines. Instead, it explores the creative lives they led, not just writing songs but forming communities of likeminded artists wherever they went. “They all inspired each other,” says Saviano. “It’s a film about friendship.”

Susanna recorded herself the way other people might write in a diary, amassing stacks and stacks of tapes during her lifetime. Because Saviano and Whitfield rely on those audio journals to tell the story, she emerges as the main character of Without Getting Killed or Caught, a complex and contradictory figure on par with the men in her life. A painter and illustrator, she was never quite as dogged in her songwriting as Guy or Townes, but in the ‘70s and ‘80s she enjoyed more success than either of them. In 1976 a Texas singer named Dottsy had a huge hit with Susanna’s “I’ll Be Your San Antone Rose,” which was later covered by Emmylou Harris and Jerry Jeff Walker.

Each new project—the tribute album, the book, the film—has offered Saviano new insights into Guy’s character and catalog, and she’s likely not done with him. She spoke with the Bluegrass Situation about exploring Guy’s music in different media, creating art while grieving, and making sure everyone is a fan.

What was your entry in Guy’s music?

I grew up in Milwaukee, which is as far away from Texas you can get and not be in Canada. My stepdad had a friend who used to come over every Saturday night and they would listen to records and turn each other on to new music. I would just hang out and listen to them talk about music all night. My stepdad was really into Memphis soul, and his friend Rudy was into country and folk. One Saturday he shows up with Old No. 1. “Rita Ballou” is the first cut on that record, and I remember sitting down with my ear next to the speaker and looking over the liner notes. It said, Words and Music by Guy Clark. I tell you, I was 14 and a real knucklehead, because that was the first time I realized that of course people write songs. They don’t just come out of thin air. People write them! I fell in love with that album, and it sent me off on a journey to find other songwriters. But teenagers are fickle, and I didn’t really stick with him very long. I certainly didn’t buy all of his albums.

Many years later I finally met him. We were at an industry party in Nashville, and we started talking. He asked me where I was from—which is one of his favorite questions. I started talking about Wisconsin and the 15,000 lakes and Lake Michigan on one side and Lake Superior on the other and the Mississippi River and the North Woods. Obviously I love Wisconsin. But I could tell he was getting bored, and he just moved along. I did a story on him later and we hit it off. He was a curmudgeonly old dude, and I happen to love curmudgeonly old dudes.

Did you know writing the book that you would be doing this movie as part of this larger Guy project?

No. I had no idea. I was in the middle of the book, struggling and not sure that I would even finish it, when another filmmaker approached Guy about doing a documentary. Guy said to me, “Look, I’ve been spending all these years with you. I don’t wanna start over with anyone else. Would you be interested in doing a documentary?” I didn’t even think I could finish the book at that point! Guy said he didn’t care if there was a documentary, but he wasn’t going to start over with someone else. So then I felt like I had to do it.

My husband is a video engineer. His day job is with Bruce Springsteen. We met when I was working in television. So I thought, Maybe my husband can do the documentary with me. We know what we’re doing. He knows all about production, and I know how to tell a story from being a magazine editor and writer. I know what a story arc is. I knew it would be hard, especially raising the money, but I felt we had to give it a shot.

When did you start filming?

We started interviewing Guy on camera in 2014, which was way deep into my writing of the book. I turned in my book in the fall of 2015, and we got our final interviews with Guy on camera that fall. And then Guy died in early 2016. My book came out, but then it took us a while to even work on the film. I had no idea what the story was. That’s the hard part—if you’re going to tell a story, you have to know what you’re going after. We didn’t know that when we first got him on camera, and we didn’t really start working on the film until 2017, when Guy had been gone for almost a year.

And I was so overwhelmed. Right after Guy died, my mom died. They’d both been sick for a while. And I was just worthless. I went out on my book tour that fall, driving around Texas in my minivan. I’d be at an event talking about Guy and signing books and taking pictures, then I’d get into my van and would just cry my eyes out. Then I’d go to the next event. That was the whole fall of 2016.

That sounds rough. How did you move on?

My husband went to Australia and New Zealand with Springsteen for a few months, so I decided I would go to Austin. I’m just gonna eat good food and walk the trail and be in sunny weather and try to recuperate from 2016. I met this guy who ended up being my co-writer on the film, Bart Knaggs. Without him I don’t think I would have been able to do it, because I had this 450-page book and didn’t even know where to start. We went to a screenwriting workshop together, and it was Bart’s idea to tell the story from Susanna’s point of view and focus on the trio of her and Guy and Townes.

That gave me my mojo back. Plus, Guy had given me all of Susanna’s audio diaries after she died. I listened to them while writing the book, but frankly a lot of them were just her and Guy and Townes drunk and talking gibberish. When we decided to write the documentary from her point of view, I went back and listened to all those tapes. Thank God I had them, because we used a lot of that. My husband digitized them, and there was a lot of gibberish but there were also these nuggets of gold everywhere. They were truly a gift.

Those tapes really humanize the three of them. Usually you have talking heads in a documentary, but these are the subjects talking.

That was one of our rules: Only the people who were there at the time can tell us what was happening. Early on, when Guy and Susanna were having the salons in Houston, Rodney Crowell was there and Steve Earle was there. Then, when Guy started touring without a band, the way he wanted to do it, Verlon Thompson was there and Terry Allen was there. It felt like we had to say, “Anyone who wasn’t there doesn’t get a voice.” Later, we did add Vince Gill to talk about what was happening in Americana at the time and what was happening in the industry, but he knows all that. We brought him in to be the thread that connects all that stuff.

How did that change your relationship to the book? Were there aspects that you wished you could have gone back and rewritten?

Yes. There was a part of me that was like, “I wish I’d known all this doing the book.” But I had to look at them as two separate projects. The book is an overview of Guy’s life and music, but the film is about Guy’s relationship with Susanna and Townes. They all inspired each other. It’s a film about friendship.

It definitely seemed like a kind of love story, although one born out of grief. I appreciated the restraint of not trying to sensationalize what could have come across as a love triangle.

We were definitely cognizant of that. Guy and I talked a lot about it, and they came up in a time that was more… free love. It’s just a different way of looking at things. People ask me all the time whether Susanna and Townes were having sex, and it doesn’t matter. It really has nothing to do with the story. They all loved each other deeply. That’s what matters.

There’s such an interesting contradiction where Guy and Townes claim they’re not interested in having hit records, yet they’re clearly envious when Susanna has a hit record with “I’ll Be Your San Antone Rose.”

I remember Steve Earle telling me that when Gordon Lightfoot had a hit with “Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald,” he (Steve) and Guy got drunk for a week. They just couldn’t believe someone had a hit with that story! They all wanted to write the kind of songs they were writing, but they wanted those songs to be hits. And they weren’t. Susanna could just go off and write from the heart and have a huge hit and make all this money.

Has there ever been a compilation of Susanna Clark’s songs? I couldn’t find any in my research.

There has not. There are a few things I’ve thought about doing with her. She left a lot of half-written songs, so I thought about asking other women songwriters to finish the songs she started and then record them. That is something maybe someday I’ll do, but the problem is finding support money. When I did my other tribute albums, albums used to make money, so there would be a label willing to invest. But now I just don’t know. There isn’t one that I know of, but I’d love to do something with Susanna’s work.

Guy got so much overdue recognition later in life. What was his attitude toward all that attention?

Oh, I think he liked it. Townes died in ’97 and suddenly became this mythical figure, and I think that rubbed Guy the wrong way. Because Guy was still working. I think he was happy that people actually liked his work. Something I found really funny was, he got a Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting from ASCAP and a Lifetime Achievement Award for Songwriting from the Americana Music Association, and he was in the Songwriter Hall of Fame. But a couple years before he died, the Academy of Country Music gave him their Poet’s Award. Guy wasn’t even really country music, but that was his favorite because it was called the Poet’s Award.

Photo Credit: Al Clayton