It’s a wonder that we journalists ever get away with describing an artist as a singer/songwriter and leaving it at that, as though the meaning of the categorization is so simple, stable, and straightforward as to be universally self-evident. Singer/songwriters, themselves, conceive of what they do in vastly different and ever-evolving ways.

Chastity Brown and Erin McKeown exemplify just how dynamic the role can be. Last week, Brown announced her signing to the folk label Red House Records and McKeown recently released her EP, According to Us, but both are at least a decade into the process of responding to their changing understandings of themselves and the world around them through their music. Along the way, they’ve recalibrated how they want to communicate in, around, and between songs. They were both up for a bracingly honest conversation about what their work requires of them.

Have you two ever crossed paths before now?

Erin McKeown: We haven’t, no. I spent a little time this afternoon perusing Chastity’s website, listening to some music. And I see that you’re on the road with Ani DiFranco right now, which I’ve done before. So I’m surprised we haven’t crossed paths.

Chastity Brown: But I’m glad to cross paths today.

I didn’t consider the Ani overlap when I asked you both to do this interview.

CB: No pun at all, because that’s one of Ani’s songs — “Overlap.” People think that women are constantly trying to compete against each other. There have been several possible opportunities of me opening for other people — other women — and managers have been real quick to be like, “No, we don’t want two women on the bill.” Ani’s ethos is really about locking arms and supporting each other, even if we do such different shit [musically]. It makes sense that we would cross paths today, in my opinion. For me, and probably for the both of us, it’s really about locking arms. The music business is difficult enough without trying to compete with your comrades.

EM: I totally agree. Some number of years ago I was like, “I’m just going to play shows and make records with people that make me happy.” Just remove the, like, “Could this person advance my career?” Any of that stuff, in my experience, nine times out of 10, it doesn’t. And in the meantime, I would just rather have a more interesting experience that arouses my curiosity, rather than just punching a clock toward some goal that may or may not materialize.

It seems to me that both of you have evolved in how you think about a particular aspect of being singer/songwriters — whether, why, and how to say things of social and political significance in your music. Erin, you sort of poked at traditional notions of gender and relationships on your album Grand, but your writing on more recent projects, including your new EP, has a different sort of directness and urgency. Chastity, the sound of your music, in itself, makes a statement about how country, soul, and R&B traditions are intertwined, but up until recently, your lyric writing hasn’t been explicitly political in nature. Could you both speak to how your priorities have changed, in terms of what you seek to express?

EM: I appreciate you pointing to what was happening on Grand. Such a long time ago, by the way. At that time, I was definitely knee-deep in trying to advance my career, and I was working with a big — not huge — but big record label at the time. … I was trying to advance my career by a blueprint that was laid out by more or less the label and a more traditional path of the people that had come before me. It’s not that I didn’t know about Ani, of course, but I was sort of trying out this thing and hoping it would work for me. I was definitely exploring politics and relationships in my music, but it was quite cautiously. Some of that was my own personal journey about my internalized homophobia and my internalized misogyny. That’s been a long journey for me of becoming more accepting and open about myself for myself, and that naturally gets reflected in songs. But, at the time, I was very sure that, if I spoke out more clearly or openly or in a less coded way in my songs, there would be some sort of commercial consequence. … Now I’m just looking for an effective song to connect with people. For me, that has been more effective, if I have been more clear about stuff.

CB: I’ve always just sung whatever’s on my mind. And in the beginning, on stuff that wasn’t properly released, it was very hippie-dippy: I love the trees. And I still do — I still fuckin’ love trees.

[All Laugh]

CB: It centered around, “What is this song about? And how can I exhaust this story but not exhaust the listener — like, get the full story out?” It wasn’t ever specifically political. But 10 years later, what I’ve realized is that the personal is political. Just by me being a bi-racial, half-Black, half-white woman living in the world in America right now is political. My focus, as far as this last record, I guess it’s really been psychological. I’m really intrigued by the perseverance of the human spirit and the complexities and contradictions that we embody as human beings. At my live shows, I use the time between songs to dig a little deeper with the folks that are listening about where these things are coming from, whether it’s a blues song that I wrote about Detroit, Michigan, going bankrupt and people losing their retirement. That song is essentially about putting your trust in something that you later realize you shouldn’t have. But if someone doesn’t know that, they might just think it’s a love song, that I’m saying “Fuck you” to somebody.

That rang true for me — what you said, Erin, about trying to be as clear as possible. But because we’re making art, there’s this room, this ambiguity. What happens when you release art to the public is, no matter what narrative I give you, you still may extract pieces of that narrative. People will make it their own and make it applicable to their own spheres. But that’s one huge realization for me as a 34-year-old woman and what’s been happening in Minneapolis — Philando Castile’s murder and last year with Jamar Clark. Just being a person of color, a queer woman of color, for that matter, is freaking political. I don’t even have to say anything; I just leave my house, and that’s a statement. I practice good eating habits and I exercise; radically loving myself is also political. I see that now, and my hope is that that comes out in my work. There are other stories to tell other than just the specifics of politics or my stances on things.

It sounds like those are realizations you’ve come to and priorities you’ve embraced over time.

CB: An author I love, Octavia Butler, she’s freakin’ blowing my mind. Such imaginative writing. She was the first Black woman to write sci-fi. I was geeking out yesterday and watching these YouTube clips of interviews with her. The interviewer asked her about her stance on current politics, and she was just like, “There’s so much that Black people can write about other than just being hated.” There’s so much more to life experience other than just constantly defending your queer self and your queer and transgender brothers and sisters. I love the way that Octavia put it: There’s far more vast creativity within us.

EM: I love that. I also love the reminder that art gets at things in oblique ways that are often just as useful as clear ways.

Erin, on your new EP, you play with the power of a person claiming an identity for herself. You noted in an interview a few years ago that, when first you began to get attention for one aspect of your identity — being queer — it wasn’t because you’d decided that you wanted to start writing or talking about it, but because a blog labeled you that way. Once there was the expectation that you’d be speaking from that identity, what’d you do with that?

EM: Basically, what happened was, I did an interview with a lesbian website. Up to that point I had never come out, and that had been on purpose. We never talked about it in the interview. Then when the article was published, the headline was “lesbian singer/songwriter.”

CB: Oh, damn!

EM: I know! I started getting these emails from people that said, “Oh my God! You’re a lesbian! That’s so great! Thank you for coming out. That means so much to me.” Besides the functional piece of I wasn’t really ready and it wasn’t on my terms, I also felt the responsibility to those folks to say, “Right on! You’re okay as you are!” Because that’s the underlying message that I would hope to give anyone. I just felt like I didn’t have any choice but to just jump off the deep end and accept that it happened and try to work on my own fear about it and try to be a kind and loving example for other folks who could identify with me in that way. I don’t identify as lesbian; I’ve always identified as queer. But I think 10 years ago that was a conversation that wasn’t as nuanced as it is now, which I’m really glad to see.

I played on sports teams in high school — I still play on sports teams — but I always hate putting on the same shirt as somebody else. I think my journey has been to try to recognize that impulse in myself and put it aside and kind of work with the identities that get foisted on me, even though they’re not always my choice or the timing is not my choice.

Once that happened, how did you make creative use of it?

EM: I ignored it. I ignored it in my writing for a while. So much of this work happens, like Chastity said, in between songs. And I’ve always been someone that likes to go out and meet folks after the show and talk. So much of this work in those spaces, as well. I just found, in those interactions, that I could make better use of these identities, if I just gave people space to put their own into the conversation with me.

Chastity, in an interview you gave a few years back you reflected that making political music had become a more isolating practice than it might’ve been for previous generations. At that time, political songwriting didn’t really seem attached to a movement. So much has happened since then. Have your feelings about that changed? Do you feel musically connected to the Black Lives Matter movement?

CB: I’ve never been so specific on stage about current events than I have as of late, on these last few tours. I think it’s this realization that my personal life is political and that I have the fortune to be elevated and amplified night after night; I’m the loudest thing in the room. And what am I gonna do with that type of power?

I came home after the mass demonstration that we did for Jamar Clark through the streets of Minneapolis and wrote this song called “Hey You.” It’s very gentle. Initially, the song was more like, “Fuck you.” [Chuckles] But what I realized was that that changed the focus. If I’m saying, “Fuck you,” that means that I’m on such high guard that I’m also not celebrating. Alice Walker says, “Where there are tears, there will be dancing.” I wanted to write a song in solidarity that sets up these different scenes of brown folk culture and is celebrating it, and then give the listener an opportunity to think about that. The song closes with a bridge saying, “I was wanting you to see me to show you that I exist, but I put that down when I raised my fist.” I would’ve never written a song like that had I not participated in these protests where we’re all crying and then moments later thousands of us are jumping in the streets, dancing to Kendrick Lamar.

I just finished watching the Nina Simone documentary. She was doing her thing; she was rocking it; she was blowing up all over the world. And then the Civil Rights movement happened, and she couldn’t help herself. I felt a kinship to that feeling: I cannot help myself. I talk about Black Lives Matter at ever single concert, and I often will follow it with a Nina Simone song, because she’s such an eloquent woman. I lean on her in that moment, and say, “If I can’t be eloquent enough, let Nina Simone do it.”

Erin, I love what you were saying about the folks who come up to you, because I also have that, especially with little mixed girls. Those of us who grew up in a small town with an afro, you’re really, really aware. And I’m not even dark-skinned, you know? But there were all these nuances that I didn’t have a language for, until I started seeking out images of myself. And there’s nothing more powerful than that sentiment. Even if I’m playing a show in front of a thousand people and I sure as hell know there are only eight people of color there, those eight people of color are definitely gonna link up after the show and just be each other’s echo or be each other’s mirror.

Because I play Americana, it’s been interesting reminding even the Black community that the banjo is an African instrument: “We’re so diverse. We’re so capable of everything.” I end up, in certain ways, educating both sides of me, the white side of me and the white audience and the Black side of me and the Black audience.

I’m glad you brought up the Black banjo tradition. You said that your very existence is political — so is your musical imagination. You have a song called “Banjo Blues” on a recent album where you’re singing over an abstract programmed loop. You’ve incorporated loops in earlier tracks, too, like “House Been Burning.” That album, Back-Road Highways, opens with a very laid-back loop that could work just as well for you if you were a rapper rather than a singer.

CB: Oh, I wish I could rap.

You incorporate hip-hop production elements and myriad rooted musical traditions, including soul, gospel, and country, into what you do. What possibilities do you see for expanding our notions of rooted musical traditions to include hip-hop?

CB: One thing I’ve always said to my band is, “If I don’t feel the kick drum, it ain’t a fuckin’ song.” There’s just something with Black folk music — the beat is essential to everything. What I layer on top of the beat just so happens to be the acoustic guitar.

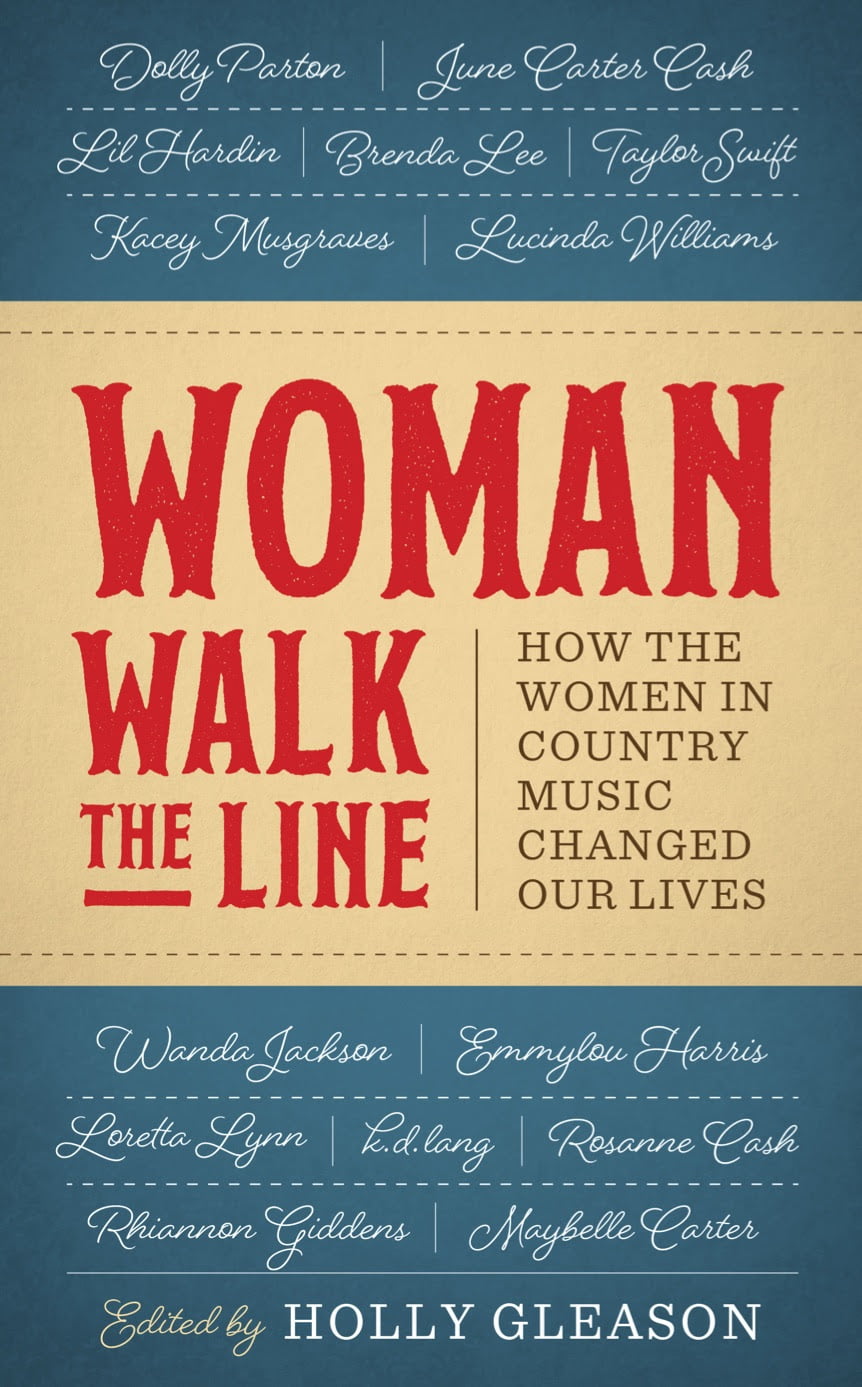

Since I’ve been playing publicly, people have always questioned me about my genre-blurring. I never had the language for it until this past year. It’s truly, I am both things; I am just as much one as the other. I love Dolly Parton just as much as I love Beyoncé, but for different reasons — or as much as I love Mavis Staples or Van Morrison or Ryan Adams. I grew up listening to Americana and old-school country, and I grew up listening to R&B and gospel, and Irish music. This is just me. If you can’t get it by now, I’m putting out my sixth album and I’ve been pretty consistent. I am soulful, and I’m country. That’s just what’s up. I feel like I’m better able to articulate that this whole duality that people are seeing is, in fact, me. It’s not a duality to me because it’s the life that I live.

EM: Chastity, I appreciate hearing your experience with the assumptions that people make and the way that you don’t even consider having to reconcile those things in yourself. There’s nothing to reconcile. It’s just you. … In the second or third season of Orange Is the New Black, it seemed like there was a tiny little theme running through the whole season where anything any of the characters had a chance to talk about what music they liked, it was never …

CB: … what the stereotype would suggest.

EM: The, I think, racist assumption that, if you’re Latina, you have to listen to Latin music, or if you’re African-American, you have to listen to soul music. I was thinking, “In what ways do I have my own version of answering these questions in my own work?” Obviously, as a white woman, I come with a different set of privileges to unpack and participate in this conversation in a different way than you do. Something that’s been important to me to do in my work is to notice these assumptions and to try to make a space to undo them with actual songs.

CB: I like that. Hell, yeah.

Musically speaking, Erin, you’ve created a lot of space for yourself to maneuver and experiment. In a previous interview, you said that rhythm is often the engine for your songwriting .

EM: Yeah. That’s always been my deal. I don’t know why or where that came from for me, but it’s always been rhythm is the most important thing to me. Then I found Garage Band 10 years ago; the premade loops in Garage Band are the canvas that I start everything on. Stuff evolves or takes left turns, but that’s been my main way of writing of for a long time now.

You’ve expanded into the producer role on your more recent projects. It has to be empowering to have the tools at your disposal to explore these rhythmic ideas and build tracks like you did for “Where Did I Go” and “Histories.”

EM: I could definitely relate to Chastity when you said, if you can’t feel the kick drum, it’s not a song. … For me, that sense of propulsion and directness and body has to be there for me to be interested in music.

I wanna throw something in here. This is something I’m thinking about for the first time as I’m listening to this conversation. It’s making me realize no one has ever asked me, as a white person, to reconcile the different types of genres that have been in my music. No one’s ever asked me that. And I think that there’s something there. There’s a dominant paradigm of “it’s not that interesting if a white person loves soul music.” People don’t question it. It sounds like, from the experience you’re talking about, Chastity, people ask you that question — "These genre that are unexpected from a person of color, why is that in your music?" People don’t ask me that.

CB: Almost every interview I’ve ever had. … That’s crazy that no one’s ever asked you. That blows my mind.

EM: They’ve never asked it to me in the context of me being white. I’ve been asked that in the context of, “Isn’t it unusual for jazz to sit next to rock in your songs?” But I think it actually is an explicitly racial question. No one’s asking me that because I’m white and there’s a long history of it being ”okay” for white people — I’m going to use this word on purpose — to dabble in the music of people who are not like them.

CB: I appreciate you recognizing that.

Erin, I’m surprised that no one’s asked you about some of your global sources, things like borrowing West African blues sounds for “The Jailer.” So that’s not a conversation you’ve ever had?

EM: I have spent lots of time with African music and love it, and it comes through in my writing because of my love of it. I always think about [the fact] that I’m a white person working with those texts, for lack of a better word. I think about that stuff and I try to be as responsible as I can. I certainly have conversations with other musicians about it. But my point was, I’ve never been asked that, in terms of people trying to make sense of my music. And I think that that’s relevant to what we’re talking about.

For more on race, politics, and community in music, read Jewly's conversation with Heather McEntire and Sweet Honey in the Rock.