Award-winning author and journalist Emma John has intensely pursued many passions through her gift of writing. Her first book, Following On: A Memoir of Teenage Obsession and Terrible Cricket, was named the 2017 Wisden Book of the Year, and her newly published title, Wayfaring Stranger: A Musical Journey in the American South, tells a story of self-discovery in the Londoner’s trip to the hills of North Carolina.

An email discussion with John (who also regularly contributes to BGS) uncovered a number of universal truths about the wide-reaching allure in the people, stories, and culture of bluegrass.

BGS: Describe the overall experience of writing this book. Were there any particularly surprising or challenging points in the experience?

EJ: There were two very distinct parts to the process. First came the trip itself, which was supposed to take six months, but got extended far longer because I was enjoying myself so much. That was the fun part, and the real reason for writing the book in the first place. What was really hard was heading back home to the UK, sitting in a tiny little study, in the middle of winter, when there are only about 6 hours of daylight, and trying to recreate all my memories without feeling really miserable that I wasn’t still in the mountains! I found a solution: I went back.

Early in the book you describe bluegrass music as “the sound of the past, being enjoyed with all the verve and vivacity of the present.” What is it that seems to make bluegrass so timeless?

I think it’s the fact that it’s always been pretty true to itself. You don’t play bluegrass to be modern, you don’t play bluegrass – Lord knows – to make money or get famous. The only people who play bluegrass are the people who really love it and can’t help themselves. I think that has given it a truly unbroken thread over the past 80 years. Plus, acoustic instruments are never going to age as badly as electropop synth music or the keytar.

It sounds like your trip to North Carolina turned your life upside down in the best possible way. How much did the sheer unfamiliarity of everything play a role in your self-discovery?

It really hit me for six, as we say over here in Britain (that’s a cricket metaphor). The fact that from my very first day in North Carolina I stumbled into – and was immediately embraced by – a world of rural pickers meant that I had to start from scratch. On every score: the music, yes, but also the food (an endless quest to source a vegetable that wasn’t cooked in sugar), the culture (lunch before noon?! what is that?), manners (if I even said ‘damn’ I got funny looks), and accents (I struggled to make myself understood because of my incredibly clipped vowels, and I often had to smile and nod when Southern folk spoke to me because I had no idea what they were saying.)

In a way it was incredibly liberating. Yes, I was an alien, but I was also someone about whom no one had any preconceptions, really. In fact everyone seemed to believe the best of me at first sight! And so I shrugged off my more cynical side, and began to enjoy and try to live up to their confidence in me. I also found the openness and generosity of American society a lot more suited to my own natural character than my own country. I’ve always been gregarious and felt that at home in London where people are quite reserved I can be “a bit much.” In the South I found myself being the best version of me I could be!

As your friend Fred is describing the many achievements of Earl Scruggs, you write, “Fred said all this with a personal pride, as if Earl’s success reflected well on everyone, including himself.” What makes bluegrass so personal to those who follow the genre, and why do people take so much pride in being a part of this music?

Again, I think this is because the music is so niche, so people feel very protective of it. If you pour yourself into something that not a lot of other people appreciate or even notice, you feel incredibly attached to it and sometimes even defensive of it. The pride can come from family connection and ancestry — ‘My great granddaddy played on this fiddle!” — or from that strong sense of geography – “This is the music of our mountains!” – but it can also, I think, just come from ‘getting’ it. Bluegrass is a language that not everyone speaks.

In describing the atmosphere of Pete Wernick’s bluegrass camp you wrote, “When people weren’t playing their favourite songs, they were talking about them.” How much do the non-musical aspects of bluegrass such as the stories and characters play a part in the culture of the genre?

Very much. In fact it always amazed me at how no one got tired of hearing the same stories do the rounds a million times in picking circles! Remember that one about Bill Monroe and the bagels? One of his bandmates brings him a bagel and he eats it and says, “This donut tastes kinda strange.” I mean, we’ve all heard that, right? At least a dozen times. But the sharing of those stories – that everyone already knows! – is part of the ritual. It’s part of the homage you pay to the music. You don’t stop someone mid-flow and say, “Yeah yeah, I know how this one ends.” You listen to someone tell you about how Carter Stanley drank himself to death, or Stringbean was murdered, or Earl and Lester fell out. It’s a grand narrative that we all belong to.

Have you returned to playing classical violin since discovering bluegrass music? If so, has learning bluegrass fiddle changed the way you think about or play classical music?

I have not. The only time I play classical violin is if I want to show off in front of a bluegrasser, and then I’ll peddle out the first few bars of “Eine Kleine Nachtmusik” or “Czardas” just to prove I know where fifth position is. But bluegrass fiddle has changed the way I think about all music. I just didn’t LISTEN to it before, or at least I listened in a very superficial way. I listened to the notes, but never the feel. I listened for familiarity, not for emotion. I consumed music so that it could fulfil a purpose, but I didn’t appreciate the utter genius of the people who were making it.

One of the interesting things about this book is that it can be enjoyed by someone who’s never heard of bluegrass equally as much as it can be enjoyed by a bluegrass veteran. What can a novice learn from your story? What can a veteran of the genre learn?

Well hopefully the novice will be interested by the very American story of this music’s history — its 19th century distillation in the Appalachian mountains, its crystallisation in the post-depression Southern diaspora, its rebirth in the hippie and folk movements of the 1960s. But one thing I really wanted people who are new to bluegrass to take from the book is the realisation that it’s a truly unique meeting place. That this kind of music can be and very much is a place where people with very different political outlooks, backgrounds, and experiences do sit alongside each other and put aside what divides them. It’s a music that demands your wholehearted commitment to the moment of playing, and in that moment, everything else gets stripped away, and you can have a pure human connection. And surely that’s what the world needs right now.

Have you discovered more bluegrass music in Europe since becoming interested in the genre? Have you found that other “bluegrassers” in Europe share a similar introduction to the music as yours?

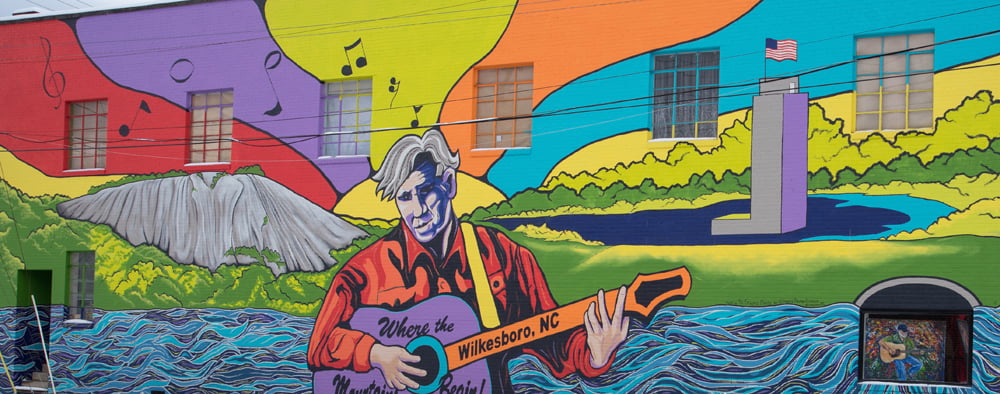

I have! I think meeting the Kruger Brothers in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, was a big turning point for me, because the realisation that these two Swiss siblings had been channeling Doc Watson for years, and come up with their own adaptation of bluegrass, was really the first time I’d understood that it was OK to have your own relationship and tradition with this music. I always had this sense that bluegrass was someone else’s music, and something that as a non-American I would only ever be “playing” at, and never have a true part in. Now I realise that music is just music and I shouldn’t get hung up on that!

Photos courtesy of Orion Books