Let’s begin with a 45 RPM record I played banjo on.

The Rick Sutherlin Orchestra was a big band based in Bloomington. Its leader Sutherlin, from a local family, was not a great musician. I remember him at the fair waving his baton at the front of the stage while one of the sidemen did the countdowns before each tune. I’m pretty certain I got the gig because Tom Hensley, who’d played bass in our bluegrass band, the Pigeon Hill Boys, played piano for the orchestra. They needed a banjo; he suggested my name. Hensley, like most of the other members of the big band, was at the Indiana University School of Music. He recently retired after over 40 years as Neil Diamond’s pianist.

A banjo solo was needed for the show, so one of the other orchestra members, trombonist Gary Potter, came to consult with me. Potter and I had been classmates at Oberlin College, playing in Dick Sudhalter’s jazz band in 1960. The following year we had roomed in the same boarding house, and he’d played bass with our campus bluegrass band, The Plum Creek Boys. Now he was at the start of a long career teaching music, principally at IU’s Jacobs School of Music.

We decided on Bob Dylan’s “Don’t Think Twice,” a contemporary folk hit. I’d been playing it with David Satterfield in our Bloomington bluegrass band. Dave, an IU Grad student from Columbus, Indiana, had lived in Greenwich Village a few years before and done some singing with Dylan at that time. This song was in his repertoire.

I loaned Gary a copy of Sing Out! that had Dylan’s words and music so he could work on the arrangement. At this point he suggested inserting the sound of the Scruggs pegs, the musical hook in Flatt & Scruggs’ “Flint Hill Special.” Scruggs had added two additional tuning pegs to his banjo. They had cams which pushed on the second and third strings, enabling him to raise and lower the pitch of each string while it was being plucked. That created a slurred note sound resembling that of a slide guitar or a pedal steel.

The performance at the fair went over well, and soon after that someone — maybe Sutherlin? — suggested we try doing a banjo + big band LP. Thus the Delmarti 45, intended as a demo, was born. The recording was made, as the label indicates, by Don Sheets. Sheets had a recording studio in Brown County on Highway 135 halfway between Bean Blossom and Nashville. He did custom recording work — high school bands, choirs, that sort of stuff — and specialized in jingles. I worked for him there occasionally. A gold record for one of his jingles hung on the studio wall.

The recording was made on the IU Bloomington campus in August 1964, at the Indiana Memorial Union building’s Alumni Hall. The band was on the hall’s stage. Sheets set up his recording equipment on the floor in front of the stage. What I recall most vividly about the recording session is how solid the rhythm section was. “The Marti Mae Singers” was Don’s wife Marti, who overdubbed the harmony voices in his studio afterward.

The record was published in the fall of 1964. Our banjo + big band idea didn’t find any takers at record companies. At the time, bluegrass banjo crossover projects like this one were already up and running, and the heyday for Scruggs pegs had passed.

Earl Scruggs invented his pegs in 1952 after recording “Earl’s Breakdown,” an instrumental that incorporated as its hook a musical trick he’d been playing since boyhood — making a slur by plucking the second string (a B note), tuning it down while still ringing to an A, and then quickly back up to B, right in the middle of an instrumental break. A quick twist! He and Lester recorded it in October 1951.

It was released at the end of the year on a Columbia single, the B side of “‘Tis Sweet To Be Remembered,” the first Flatt & Scruggs title to make the Billboard charts. All winter long, Columbia advertised the single as a best-seller. The band, then based in Raleigh, was playing it on the radio and the road daily.

At the same time as he installed the new tuning peg he placed an identical one between the third and the fourth string so that the third string could be moved down from a G to F# and back.

Earl did this because moving the second and third strings down is a natural part of tuning the banjo from an open G chord (the default, for Scruggs-style) to a D chord. This boyhood musical trick came from something he did whenever he played at a dance — change tunings. Certain dance pieces were in G, the most frequently used tuning. Others were in C or D, each with its own tuning. Scruggs used all three throughout his musical life.

In the spring of 1952 Earl could use his new tuners not only for “Earl’s Breakdown,” but also to move quickly from G to D in order to play “Reuben,” the old-time tune that had launched him as a three-finger picker, which he often picked with the band.

That fall, just after moving to Knoxville, they recorded “Flint Hill Special,” Earl’s newest composition. It used his new pegs for the tune’s hook. This riff came at the start of the recording and was repeated at the end of each banjo chorus. That’s what Gary Potter incorporated into his charts for our version of “Don’t Think Twice.”

Released within weeks as the B side of “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke,” “Flint Hill Special” was advertised by Columbia as a best-seller all spring of 1953. It got a lot of radio play.

“Foggy Mountain Chimes” was released in November 1953. The following month Decca released a single recorded in Nashville by the Shenandoah Valley Boys. On one side was “Plunkin’ Rag,” a new banjo instrumental with yet another Scruggs peg hook.

With the pegs as with every other aspect of his music, Earl Scruggs was being listened to in Nashville and copied by young banjo players everywhere. “Plunkin’ Rag” was just the start. More about that next time!

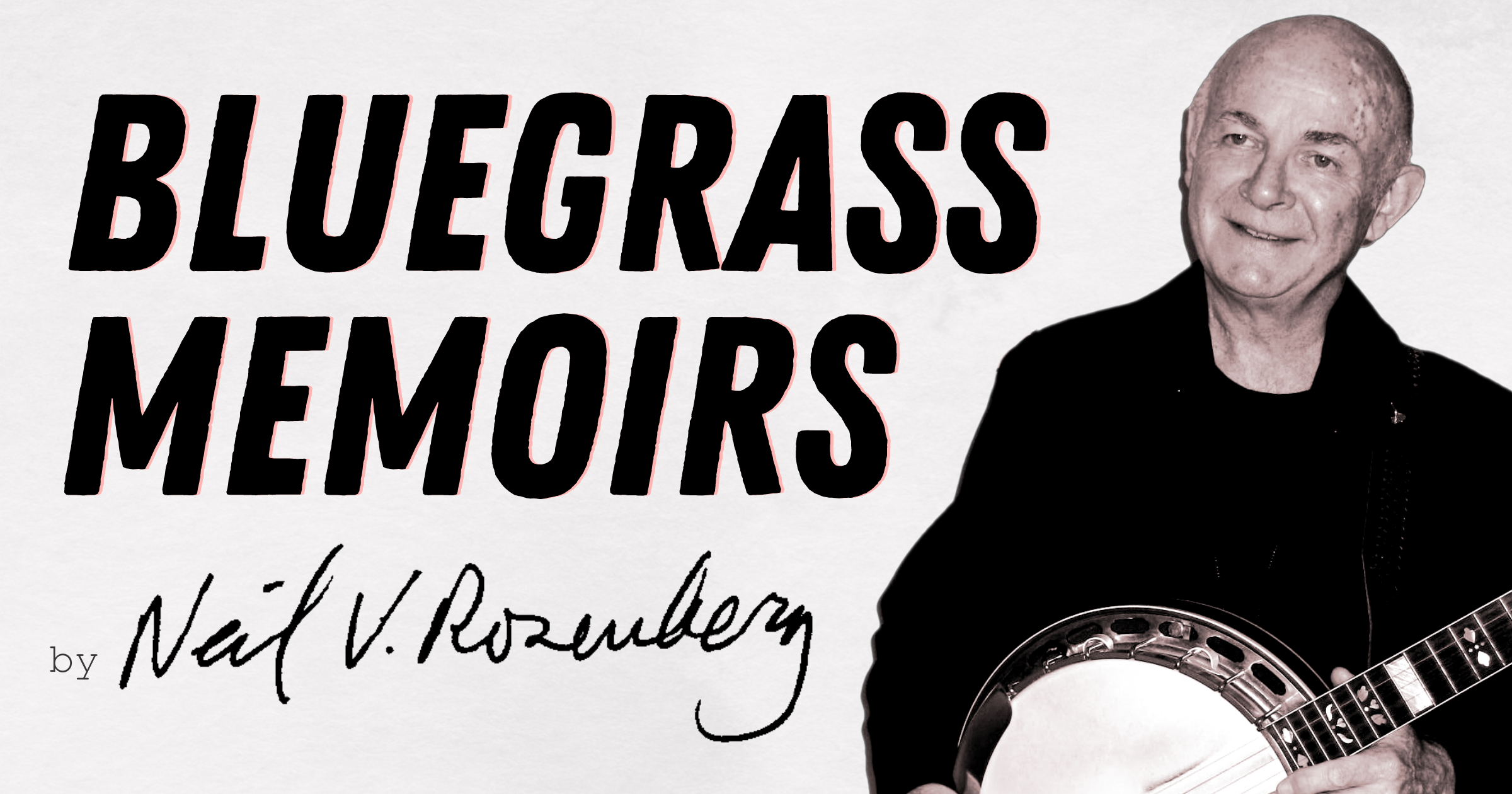

Neil V. Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, and Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg: Terri Thomson Rosenberg