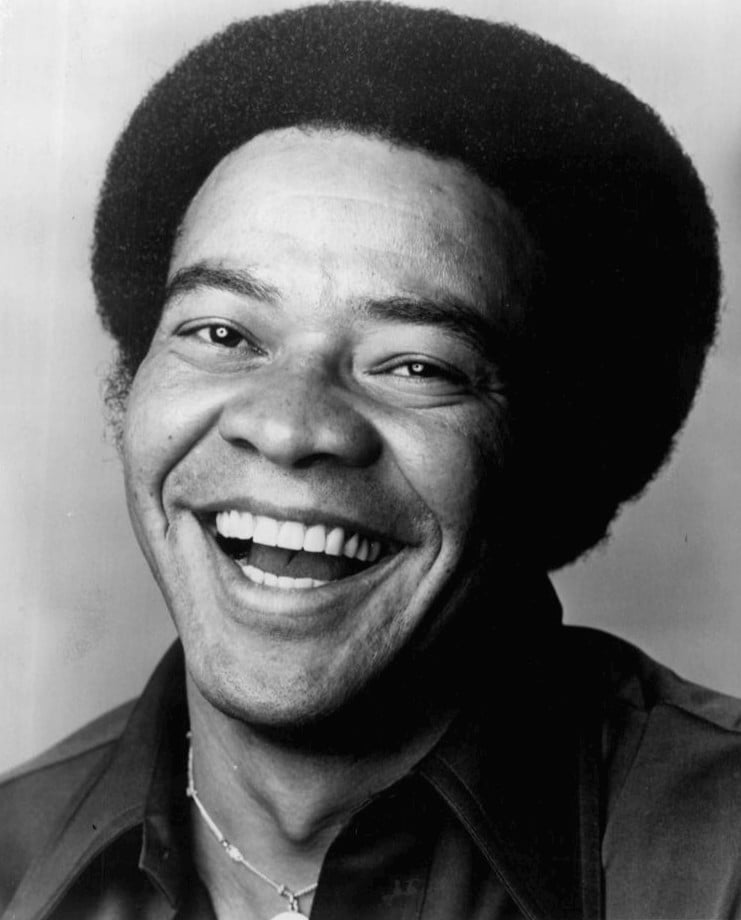

To escape the wilds of West Virginia, a young Bill Withers joined the Navy, where he worked as an aircraft mechanic. After his service, he landed a job in an airplane parts factory, but soon realized he could get girls by singing, so he decided to give it a shot. He taught himself guitar, wrote some songs, and got a deal with Sussex Records. Fun fact: His first single — the Grammy-winning, platinum-selling “Ain't No Sunshine” — was inspired by the 1962 movie Days of Wine and Roses starring Jack Lemmon and Lee Remick.

Withers kept up that pace with a string of hits that included “Grandma's Hands,” “Lean on Me,” and “Use Me.” After three records on Sussex, he shifted over to Columbia in the mid-1970s, where he released a few more albums … and encountered a bit of resistance. The label execs, which he called “blaxperts” because they were trying to change his sound to sell more records, all but halted his career. Withers has commented that he found it hard to swallow that his label would put out a Mr. T record while preventing him from releasing anything.

Though he collaborated with other artists and issued one more LP, 1985's Watching You Watching Me, Withers pretty much walked away from music. Since then, he has noted, "What few songs I wrote during my brief career, there ain't a genre that somebody didn't record them in. I'm not a virtuoso, but I was able to write songs that people could identify with. I don't think I've done bad for a guy from Slab Fork, West Virginia."

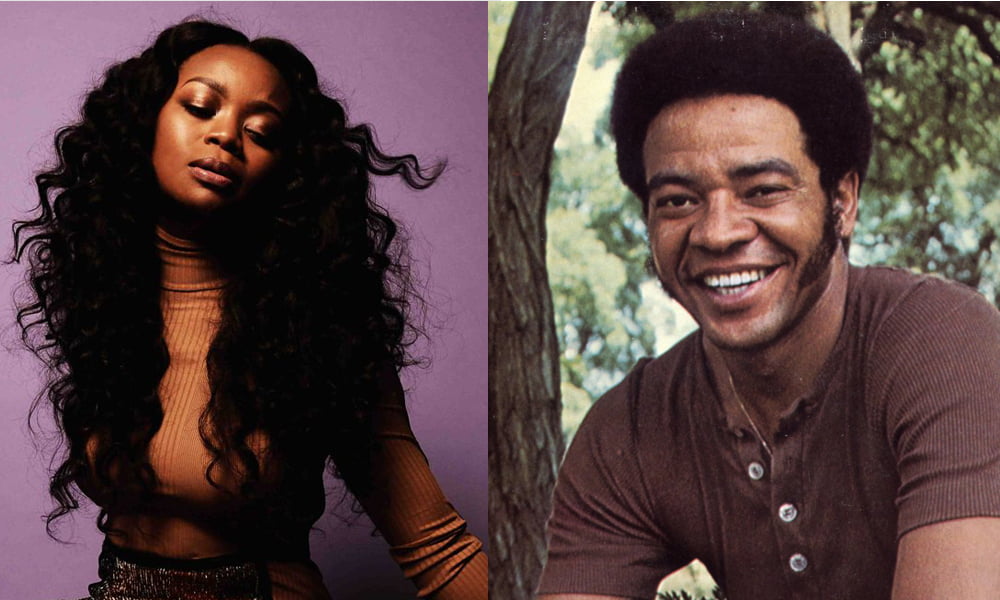

Singer/songwriter Ruby Amanfu was born in Ghana, and moved with her family to Tennessee when she was three years old. Growing up in Nashville, Amanfu couldn't help but gravitate toward music, studying at Hume-Fogg Academic Magnet School before heading off to Boston to attend Berklee College of Music, and finishing up back home at Belmont University. Around the time that Amanfu had a dance hit in Europe (2001's “Sugah”), she also connected with Sam Brooker in Nashville, and the two began writing, recording, and performing acoustic soul as Sam & Ruby. A handful of years on the road landed them a deal with Rykodisc for their debut LP, The Here and the Now, in 2009, and a follow-up EP, Press On, in 2010.

Appearances on NBC's The Sing Off (Season 3) and Jack White's Blunderbuss — as well as collaborations with Brittney Howard, Wanda Jackson, Patti LaBelle, Ben Folds, Chris Thile, and others — eventually led to Amanfu's latest release, Standing Still. It's a collection of songs by Bob Dylan, Brandi Carlile, Jimmie Dale Gilmore, Woody Guthrie, and the Heartless Bastards stunningly re-imagined and rendered in Amanfu's smoky soul voice.

Bill got a late start, but he came out of the gate with “Ain't No Sunshine” and followed that up with “Lean on Me” and “Use Me.” Even now, when he talks about those songs, he plays them way down … as if they hadn't made a mark on music at all. But we know better …

Yeah, yeah. In everything I've seen and heard from him, when he speaks or when people write word-for-word what he's spoken, he seems to be the epitome of humble. And it is so opposite of what most artists are. Most artists feel like, “Well, I need to be not humble because I have to act like I'm the greatest so that other people will believe I'm the greatest.” I'm just so fascinated by Bill Withers, and I adore him so much because he is so humble. And I think that's kind of the mode of operation that is more enticing, at least for me — in how I like music and how I receive music. If I have an artist who is like, “I'm the shit!” then I'm probably, just out of spite, be like, “Uh, nope. You're off my list.”

And yet you recorded a Kanye West tune.

Oh, I sure did. Guess what? That was a battle to the bank, honey. That was a battle to the bank. I had a couple of producers on this project and sometimes you gotta listen when people talk. There were obviously things I had to come around to, and I had to come around to that. What I heard in that song … when “Street Lights” was presented to me, I heard lyrics that I connected with. I heard a story, when I stripped away all of that production and I stripped away his voice, and I just received the words. I was like, “Oh, damn! That's actually legitimate.” He co-wrote that with a fella, Mr. Hudson, who is a brilliant writer and producer. I couldn't do a disservice to Mr. Hudson just because Mr. Kanye West was out there shootin' and salutin' and highfalutin! [Laughs]

[Laughs] That brings up an interesting point. To me, classic R&B like Bill Withers, you can feel the rhythm and you can hear the blues. That's not always the case in contemporary R&B. Sure, there's a slickness to the new stuff, but is there a more significant difference in the artistry between then and now?

Well, yeah, I'd say. With someone like Bill, I don't even know if he knew what slick was. And I think, now, I don't know why this happened, but part of me thinks that, as the world continued, as the years went by, as technology increased, I feel like people — artists and record labels and producers — I think they felt like they had to do more to keep fans' interest and attention. The attention spans, I do believe, have become less and less long. So I think there can be a bit of desperation where some of it is concerned.

I won't say it's all of it because I still listen heavily to R&B, currently. Sometimes you definitely hear production where you're like, “Man, slow your roll. Let's just hear the song.” But there's still a lot of classic-sounding singers out there who are still doing it. Even somebody like John Legend, when he just strips it away and it's him and the piano, he's a great example of somebody … you know that he gets that it's just about the openness and the vulnerability of the music. The attention span is shorter, so you gotta get hyped quickly. Obviously, I didn't do that on this record. [Laughs] I'm trusting that people will be able to take a breath and listen to this record from a completely open place. That's how I fit into this whole thing.

Right. Another difference is that, in the mid '70s, Bill released an album a year for five in a row. To be that prolific and, then, to just turn it off … because he kind of counts that as the end of his eight-year career. What does that take — because he wrote all his own stuff?

I know. I think he got fed up with the system which … [Laughs] is not hard to do. I got my first record deal — I was a baby — in 1999. Even then, the system was baffling. I did it as a means to an end … record deals and management deals and all of that. But it felt sickening on a number of occasions. I did it, but I can see how he, who is who he is unapologetically and is so homegrown and so grounded, that he was like, “You don't care about me. Why am I going to care about you?” This man who was … at first, he still kept his other job, even when he had a couple of hits. That's brilliant because he wasn't resting his laurels on that. Then, the labels were taking advantage of him. I heard once that he'd had a couple of hits and he was going to put out this album and his label said, “We don't hear a hit on that.”

Yeah, they wanted him to cover an Elvis tune.

Oh my gosh, that's right! “In the Ghetto.”

Yeah.

What did he say? Something like, “That's like asking to buy the bartender a drink.” Or something like that. And he was like, “I'm not going to go there.” It cracked me up. Because, exactly! They don't get it. They don't get you. That's the separation that has been cycling through the business.

I will say that I have seen a big difference here, in 2015, because everyone got hip to what was going on and got wiser, started to change the system to make it a little more genuine … at least for indie artists like myself choosing different paths that allow us to have creative rights again, and freedom. But Bill, at the time, was like, “No. That's not good enough for me.” And I respect that.

Well, when one of your A&R guys tells you, “I don't like your music or any black music, period” … you're not off to a great start.

No. No. And that's the thing … he knew it. He was like, “I'm gonna try this out and see what people are talking about.”

[Laughs] Or not.

Yeah. “That's what I thought you were talking about. Goodbye.” [Laughs] It's brilliant. And I'm like that, in a way. I don't think it was arrogance with Bill, and I'm not like that. But I definitely have convictions and sometimes people don't understand or relate to my convictions. But I still stand by my convictions. I have to. I think … I know for a fact, actually, that I have been inspired by Mr. Withers because of that. Because you can stand by your convictions and still do what you do, still be out there doing the music. I oftentimes say that, if I were ever to get to a point where I was surrounded by a team of people who didn't get that, then I would gladly, happily walk away and go put on my apron and start cooking in the kitchen. I would do that. But I'm really lucky right now. It's been a long time coming. This team around me totally gets me — what a concept — and supports me. We'll ride it out that way.

But there are no Withers' tunes on your new album. Are there deep cuts of Bill's that you love?

Well, “Grandma's Hands” I love so much. It's funny … the first version I heard of “Grandma's Hands” was … [Laughs] “No Diggity.”

Oh, yeah yeah yeah. [Laughs]

Sam [Brooker] and I had looked through a bunch of his songs to see what we could maybe do because I've always wanted to do a Bill Withers song. There were some on the short list for this record, too, but I had presented Sam with a song from Still Bill called “Who Is He (And What Is He to You)?” It's so simple, but that song is one for me.

Me'shell NdegeOcello did a pretty slamming version of that one.

She did. She nailed it. That's why I was like, “If Sam and Ruby are going to do it, it's going to be different.” But that's the thing … you bring up a good point … I find myself in that situation because there are some songs on this record that I'm like, “People I admire and respect have done slamming versions of these songs, but they mean so much to me and I believe in them so I'm going to go for it.” Not to do a copied version, but do something different. Obviously, when Brandi Carlile spoke up that she liked what I'd done [with “Shadow on the Wall”] … It was stressful. I was nerve-wracked to do that because I knew what she'd done with it.

But, anyway … the song “Hello Like Before” is amazing. “I Wish You Well” … but that's more of a hit than a deep cut. “Make Love to Your Mind” … that's a great one. That's the thing, just too many.

Photos by Shervin Lainez and Columbia Records