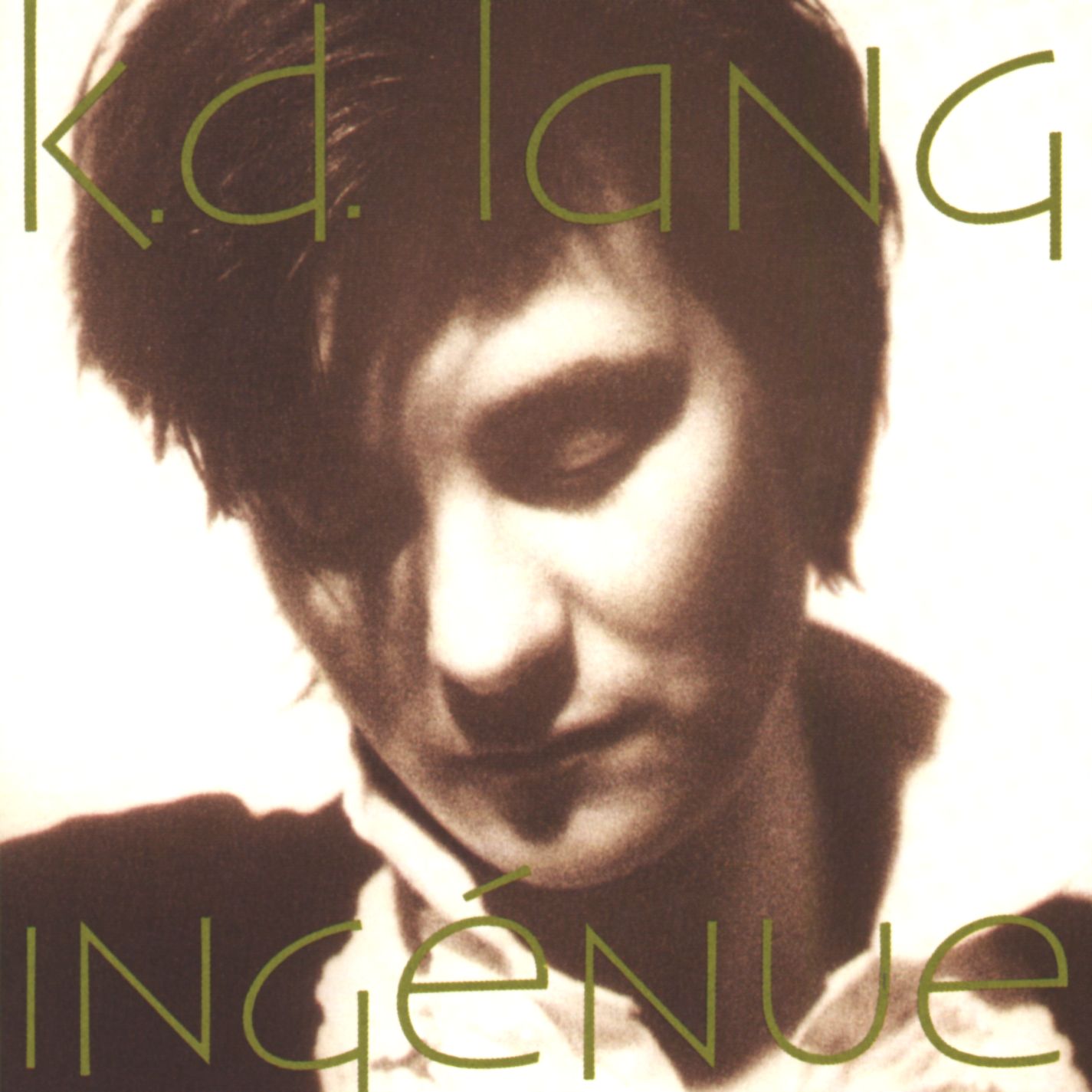

For better or for worse, k.d. lang’s 1992 breakout album Ingénue will always be associated with her coming out. Throughout the late 1980s she had established herself as an unlikely country star, a traditionalist who sang like Patsy Cline and worked with Owen Bradley but whose short punk haircut and androgynous persona branded her as an eccentric like Lyle Lovett. Also, she was Canadian—not a roadblock to country stardom (see: Anne Murray, Shania Twain), but certainly another way in which she was an outsider in Nashville. Nevertheless, she made a place for herself in the country mainstream, winning a Grammy for “Crying,” her 1989 duet with Roy Orbison, and the album Absolute Torch and Twang, released the same year, proved a more-than-modest hit, peaking at No. 12 on the country charts.

And yet, there were rumors that lang was… well, you know. She had come out to her family, but had not made that an explicit part of her public persona, despite playing a lesbian in the independent film Salmonberries. So the media pried into her personal life, posing uncomfortably direct questions to which she carefully measured her answers. lang was going to be made a spokesperson for the LGBTQ+ community whether or not she wanted that responsibility. The pressure came from within that community as well as from without. According to Newsweek, Queer Nation, an activist organization founded in 1990, put up posters around New York with photos of entertainers branded with the words Absolutely Queer. The Advocate outed a top-ranking military official at a time when gays were not welcome in the military, just prior to President Clinton’s infamous “don’t ask, don’t tell” waffle.

To preempt being forcibly outed—essentially, to take control of her own story rather than let someone else come out for her—in 1992 lang gave a lengthy, at times very tense interview to The Advocate. Her sexuality was discussed only generally throughout the exchange, with lang officially calling herself a lesbian near the end of the article. “I feel like it’s a part of my life, my sexuality, but it’s not—it certainly isn’t my cause. But I also have never denied it. I don’t try to hide it like some people in the industry do.” This was largely unexplored territory for any artist, especially one in a traditionally conservative genre and especially one who was going to so radically change her sound.

In retrospect it’s hard to convey just how chancy and therefore how pivotal Ingénue was for lang, who rejected absolute twang for torch songs rooted in jazz and pop, in chanson and klezmer, in Gershwin and Weill, Holiday and Dietrich. She described it at the time as “postnuclear cabaret.” Especially in the 1990s when changing your sound or courting a wide audience could be viewed as selling out, the album was a calculated risk, a means of shedding a long-held persona that might alienate old fans without attracting new ones. Gone were the fringed Western wear and the Stetsons; what remained was that haircut and, most crucially, a voice that sounds like a starry midnight.

The personnel didn’t change, but her approach certainly did. lang worked with co-producers and co-songwriters Greg Penny and Ben Mink, the latter a member of her backing band the Reclines. But this is not a case of treating country songs to new arrangements. The change happens at a conceptual level. Ingénue is lang’s first collection of entirely original material. She and Mink wrote songs outside the country format to find new ways to use her voice and new emotions to express. “Season of Hollow Soul” sounds like a Weimar torch song, as though the singer is playing both Annie Bowles and Cliff Bradshaw in Cabaret. “Miss Chatelaine” is an exuberant love song that cheekily references lang’s own iconography, in this case the cover of Chatelaine magazine, which in 1988 named her Woman of the Year. To contrast the photograph’s Nudie suit glory, lang toyed with her own androgynous look, even performing in a formal gown on Arsenio Hall.

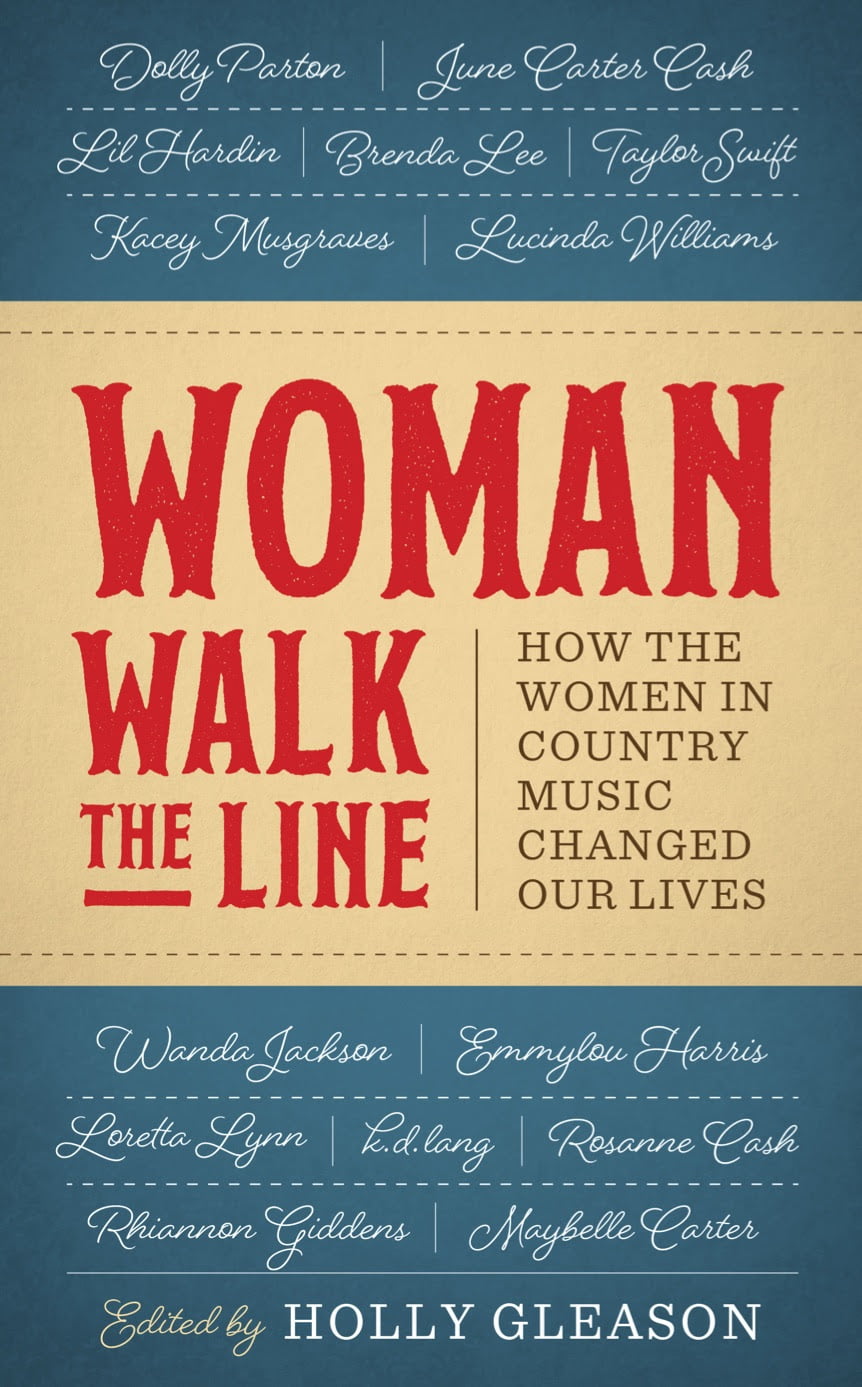

Deep into the twenty-first century, of course, country music seems by nature a porous genre, one which artists drift into and out of constantly, whether it’s a pop star looking for a career renewal (Darius Rucker), a tourist taking snapshots of Music Row (Sheryl Crow), or a country star looking to broaden their audience (Taylor Swift). But perhaps no artist has made that transition with more grace and finesse—with more sense of the inevitable—than lang, whose voice was so much bigger than one genre could contain. Ingénue not only showed how artfully she bend that voice and suppress that twang, but also demonstrated how she could use it to inhabit a very different desire than the pop charts typically allowed. For that accomplishment she’ll receive the 2018 Trailblazer Award at the Americana Music Honors & Awards in September.

The album has been tied to her coming out, a vehicle for her ascension not merely as a pop star but as a gay pop star. This is, of course, not the only interpretation of the album, but it’s one that lang herself reasserted in interviews. She was forthright about the inspiration for the album, confessing that it was inspired by the end of an affair with a married lover. lang was still in love, but accepted that the relationship was impossible; that contradiction became the spark that illuminated these new songs. No names were given, but the implication was that this married lover—the subjects of the lyrics, the object of desire—was a woman. This seems even more radical than the Advocate interview, a means by which lang insisted these songs were personal, first-person, and grounded in gay desire. “Can your heart conceal what the mind of love reveals,” she sings on “Mind of Love,” and if you miss that she’s talking to herself, she calls herself by name: “Why do you fight, Kathryn? … Why hurt yourself, Kathryn?”

Yet, Ingénue is about desire, not orientation. These songs express a sexual, physical, and emotional yearning that is specific to her as an individual, specific to her as a lesbian, but she conveys it in such a way as to be universal on some level: something that might resonate with any listener, regardless of their orientation or even their opinion on orientation. In 1992 this might have had a humanizing, normalizing effect, because the risk paid off and then some: Ingénue was an immense crossover hit, anchored by the smash “Constant Craving.”

That song in particular has stuck with lang ever since: her signature tune, a mainstay of every concert she performs. “I knew it was a hit, and I was mad at it for that. I felt that it was a sellout at the time,” she told the New York Times earlier this year. But it’s not hard to see why the song would resonate with her audience, as it expresses a resilience in the face of prejudice or suspicion. “Even through the darkest phase, be it thick or thin,” lang sings in that voice, which sounds neither angry nor outraged but observant, matter-of-fact, as though a “darkest phase” was natural. “Always someone marches brave, here beneath my skin.” lang draws out those syllables in the chorus, pushing against the backing vocals, putting her words on the off-beats, drawing out those syllables—the consonants in “constant,” the long vowel and sensuous V in “craving”—to hint at possibilities: Craving for what or for whom? Constant as both heroic and burdensome, never satisfied?

Whatever it might mean to any one potential listener, it “has always been.” This craving is natural, lang insists, coded deep into all humanity, as constant in 2018 as it was in 1992.