Hiss Golden Messenger, the sobriquet or “umbrella” under which singer/songwriter M.C. Taylor plays, has always been about questions: seeking them, asking them, and abiding in the kind of creative space that holds high the old adage about journeys surmounting destinations. At a time when it seems like Google can answer nearly anything for anyone — yes, even more existentially inclined questions like “What job should I hold?” or “Where should I live?” — Taylor seems to prefer existing in the kind of creative waters where queries act like ripples, each leading toward the horizon. Where they arrive, whether they arrive, is an act of trust.

With Hiss Golden Messenger’s new album, Heart Like a Levee, the questions mainly revolve around the fear that comes with throwing off the mantle of a full-time job and instead pursuing a creative life. For a man with familial responsibilities to consider that act doesn’t just involve “developing wings on the way down,” as Kurt Vonnegut once described, but something far more daring. After all, what happens to art if it’s required to pay the bills? As it turns out, taking that leap has produced one of the most striking albums from Taylor’s already impressive Southern folk repertoire. If the first three songs feel like a natural extension of his previous work, things take a shattering turn on the fourth, “Like a Mirror Loves a Hammer.” The song’s entire construction feels otherworldly. The main guitar riff practically pulses while Taylor’s voice comes across not in the assured rasp of his other songs but in a higher-register whisper. Then there’s the saxophone: Delivered with punctuating grit, it rubs against the melody like sand paper, polishing the entire, beastly thing down to a dark gem. If music — for any musician who has lived long past debut and sophomore albums — involves departures, then Taylor’s new album and this song, in particular, has cast listeners off into new waters. It’s an adventure worth every note.

Hiss Golden Messenger, as a name, suggests someone who delivers answers, and yet there’s this overarching theme of questions that arises in your songwriting. What do you make of the juxtaposition involving a messenger who arrives questioning?

I’d not ever thought of that before, I have to say. I don’t think very much about the name of my band. Maybe I should because I get asked about it a lot. People ask me where does the band name come from and I don’t have a pat answer.

Maybe I can expand it then. I can’t help but think of mythology or old folk tales when I hear your name, and those stories purport to teach us something by offering us lessons. But things seem so uncertain in today’s world. Do we live in a time when our mythologies can only exist as questions?

I’ll put it this way — this is not an answer to your question, but it’s as close as I can get — I’m not interested in art that offers me answers; I’m far more interested in art that poses questions. And I have a lot of personal questions. Hiss Golden Messenger, as a project or an experiment or umbrella under which I work, is one that allows me to work out a lot of very personal stuff, sometimes under cover of metaphorical language and sometimes not at all. My music is about communication or missed communication. I think that all of that necessitates a lot of questions. I just have a lot of questions. Sometimes I want the answer, and sometimes I don’t want the answer, I just want to know what the question is.

I don’t think you’re alone in that. There is a sense that answers aren’t necessarily end points.

That’s why some people — not a ton, but more and more — are drawn to this music. I just have some questions and I know that these are not totally unique questions. They’re questions that a lot of people who are growing up in this place and this country have.

More every day with each news story.

Yes.

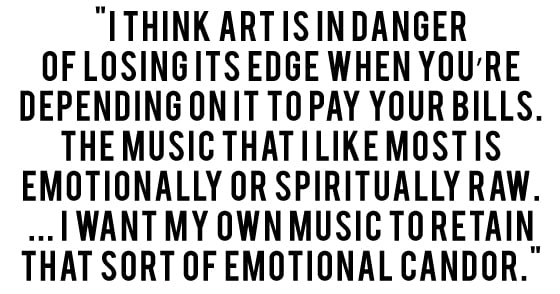

On “Cracked Windshield,” the fear that your art must take on the added burden of financing your life comes into full view. What do we lose from art when it must suddenly pay the bills?

I think art is in danger of losing its edge when you’re depending on it to pay your bills. The music that I like most is emotionally or spiritually raw. That doesn’t have a lot to do with how the album sounds, but it has more to do with the way the melody is delivered. I want my own music to retain that sort of emotional candor. I don’t know, when you start depending on your art to make a living you really … it’s easy to second guess a lot of things.

I can see that. The line you have, “A song is just a feeling, when you make it pay the rent,” really strikes at that. Do you think anyone who is too coddled by success loses touch with that edge?

No, not really. If you can disassociate your art from the money that you make from it, I don’t think so. There are a lot of examples of artists that were very successful who made very powerful, emotionally moving art. I was out running this morning listening to mid-period Aretha Franklin. She was a big star at that point, and those records are about as powerful as you can get on an emotional level, I think. So, no, I don’t think so, but if you’re using your … This is a tricky subject and not really one I know a ton about. There are some people who make art as a method to get rich, and I think you’re setting yourself up for some weird situations, if that’s the case. I’ve been making records for so long with no feedback, and certainly wasn’t making any money at all. Part of my journey was figuring out a way to be satisfied with the art when nobody was listening to it. And to figure out a way to evolve my craft and grow as an artist when, really, it was me and a dozen other people who were hearing songs. That was, at times, a thankless sort of journey, but I’m really glad I’ve been on that road because it’s kept the aesthetic parts of making music at the forefront of what I do.

It seems like that’s an interesting foundation from which to grow.

The road has been a very, very long one, from when I started to this particular phone call right now. It’s been a long journey. I haven’t changed up what I think of as my source material since I was in my early 20s, so for 20 years I’ve been trying to make a record that sounds like Heart Like a Levee and I wasn’t supposed to until now.

Isn’t it funny how it comes down to timing? You have to hit that mark in your life.

It really does, and you have to get to a point where the work feels genuine, where the words coming out of your mouth feel like they’re real and they mean something to you, like you have something at stake in singing them.

You mentioned your journey and I’m taking this question more literally here — in terms of all the different places you’ve been — but Biloxi, Birmingham, Atlanta all arise as place names in your music. How do places leave their mark on you?

Oftentimes, it has to do with the number of syllables that are in the name. [Laughs] Sometimes I need that many syllables. I don’t know. A lot of the place names that appear on Heart Like a Levee are in the South, the Southeast. The cultures of the South will always be a very important part of what I do and I’m not ashamed of that at all, and that’s not something I would really try and hide. A lot of the places in the South are places I’ve passed through traveling around on tour. And they’re places that have, occasionally, a personal significance for one reason or another. Others are places that you can’t help but go through every time you go out on the road, like Atlanta is one of those places. Other places like Plaquemine, Rosedale … if you’re a student of the South — student, broadly speaking — these are beautiful places to pass through. Maybe they’re not places you want to stay for one reason or another, but they’re places that are important to the universe of the South.

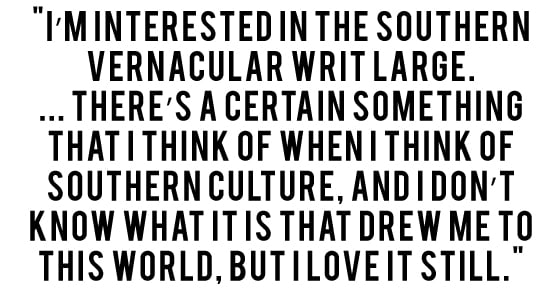

Speaking of that universe, I understand you like to read Cormac McCarthy, Barry Hannah, and other Southern writers.

I’m interested in the Southern vernacular writ large. I grew up in California and I’ve always been drawn to that particular Southern groove. And I don’t mean just musically. That pocket exists in literature, it exists in food, certainly, it exists in visual art, in photography that comes from here. There’s a certain something that I think of when I think of Southern culture, and I don’t know what it is that drew me to this world, but I love it still. It’s still something that brings me a lot of joy and makes me think a lot.

I like the word groove because the South can suck you in — not everybody — but it can get you.

Some people can take it or leave it; some people are expressly trying to avoid the South.

Or their ideas of it.

Yeah, for sure. And some people are tuned into that frequency that is like you have to be there. If you know it, then you know it; and if you don’t, it’s hard to explain what it is. Kind of like the whole idea of groove. You can’t teach groove. You’re either born with it or you’re not. And if you don’t have it, you can maybe get close to it, but you’re never going to have it.

I’m not sure why, but it reminds me of the number of MFAs that graduate every year. They may be technically proficient writers thanks to that training, but not everyone has groove.

Oh, it’s something I talk about all the time. I call him my manager, but he’s also one of my best friends, Brad Cook. We were talking about this yesterday. It seems like more and more we have these conversations with people that are technically very intelligent, and it’s like, "Yeah, I know you’re smarter than me, but believe me, I know. I don’t know how to communicate to you that you don’t know what you’re talking about, but you’re going to have to trust me." To start to talk about something like groove is to talk about feel of something, and feel enters into very subjective territory, and that’s where people don’t trust their instincts. One way to deal with that distrust or the entering into that unknowable atmosphere is to fall back on numbers or figures, when really you just have to trust the feel. If something feels good, then you gotta go to that place with it.

Your career and the amount of time it’s taken to get here makes sense then. It may have taken 20 years, but you’re following the feel, you’re not falling back on a study of something, necessarily.

I’ve certainly made a lot of mistakes along the way, and those are very valuable.

It’s not a bad thing!

It’s great. I embrace the stuff — even the stuff I might have a tiny bit of regret about, I’m glad that I did it because it was yet another reminder that you’ve gotta follow the feel.

For more adventurous Southern folk music, read Amanda's interview with River Whyless.

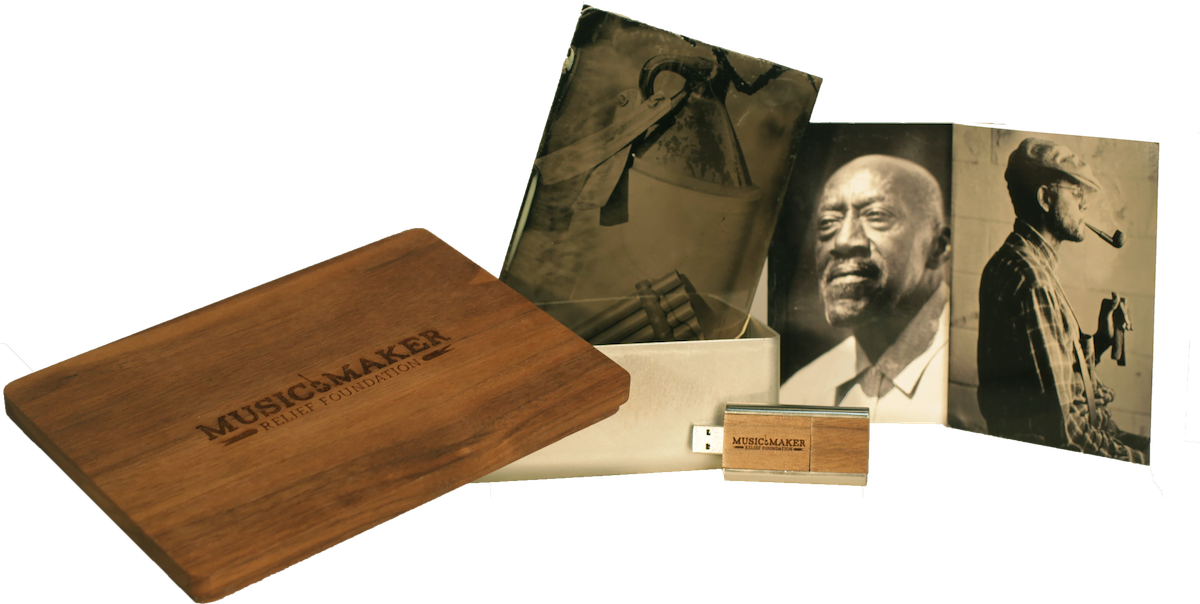

Lede photo courtesy of the artist