When Will Anderson decided to start a business with his friend Jacob Henley in 2012, he, like most people, hoped to do work he was passionate about. Lucky for him, he was passionate about a lot of things: woodworking, surfing, skating, being outside. "My brother and I grew up on boards," he says. "Whether it was surfboards or skateboards, we were always outside. We had parents who didn’t allow us to sit around the television and we never had game systems growing up. We were outside all the time, year-round."

None of those passions, however, rivaled what he felt for Salemtown — his small, low-income neighborhood just outside of downtown Nashville — and his neighbors. He wanted to find a way to use his passions to contribute to the well-being of his neighborhood, beyond just playing basketball at the local community center. After a little planning and a lot of help from friends, Salemtown Board Co. was born.

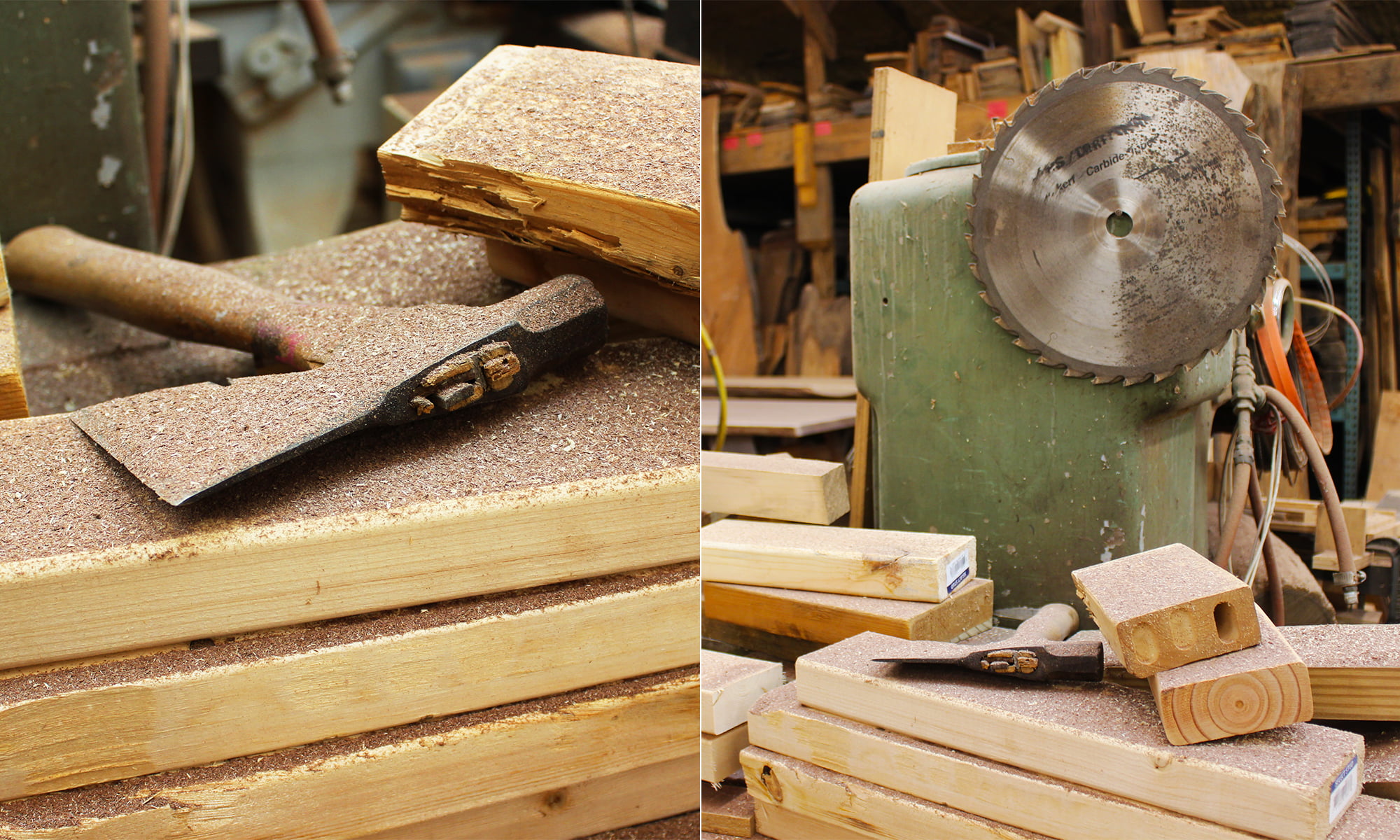

Salemtown Board Co. makes and sells handmade skateboards in North Nashville. The boards themselves look like art pieces, hand-cut and sanded maple decks painstakingly screenprinted and veneered in the small woodshop at the front of the company's property. Since opening, the company has also grown to sell apparel, accessories, and home goods, including handmade cutting boards. A glance at their online store shows a wide variety of boards, many of which celebrate the company's home neighborhood of Salemtown.

Anderson and his brother Schuyler, who now run the company together, keep Salemtown at the heart of all of they do. While the company was partially founded with the goal of creating beautiful skateboards that would, as Anderson puts it, "get people outside," its primary mission was more local: employing young men from the Salemtown neighborhood. "I had a background in social work and really felt the tension between how to see, specifically, young men go from being the recipients to being the primary drivers in their own success," Anderson explains. "I just felt like the best way I could be of help to my neighborhood was to start a business that intentionally created employment for young men who needed it. There was definitely, ‘How can we impact and invest in the community?’ Also, especially as an outsider to the community — as someone who moved in as opposed to someone who was raised there — part of it was figuring out what are ways in which I can be involved."

The company had humble beginnings, operating in its infancy out of a borrowed woodshop and growing through word of mouth. "Initially, when we got started, we painted boards in our front yard and carports and drove about an hour-and-a-half outside the city to go to a borrowed woodshop to make boards," Anderson explains. "With the young men, they were just guys we knew from the neighborhood. There has never been any secret to finding people. It was just living in the community and hiring people that we knew that needed jobs."

For the next three years, the company continued to grow, with its home city of Nashville growing right along with it. The landscape of the city changed, and Salemtown Board Co. felt those changes acutely. Last year, Salemtown Board Co. made the move from its namesake Salemtown to North Nashville's Buchanan Street, where several other local businesses were also setting up shop. Anderson and his team felt that the neighborhood surrounding their new North Nashville storefront, workshop, and skate park (which was donated by country star Kip Moore) was better suited to the company's mission. "Part of it was the growth of the company, but also a big part of it was, with what we set out to do, there was just no longer a need for the type of employment that we were providing in Salemtown," he explains. "As a result of gentrification, the young men that we started the company to create employment for no longer lived in that area. So there was the need to relocate."

Like many other Nashville neighborhoods, Salemtown was hit hard by the city's growing pains, with long-time residents getting forced out of their homes to make way for new construction. For the residents who managed to stay in their homes, new neighbors often meant new problems. "The final kick in the butt was when we had an employee arrested in that neighborhood for a crime that he did not commit," Anderson says. "He generally fit the description of the person who had committed the crime. It was a really traumatic experience for everyone involved. He ended up spending three weeks in jail before they were able to prove that he couldn’t have been there with Wal-Mart security camera footage. That experience still haunts him. There were news stations that just refused to take the story. This is a kid who is not a felon. He’s not a bad kid. But for the rest of his life, when you Google his name there’s going to be a picture that pops up of his mugshot. His public defender didn’t even believe him."

Since the incident, Anderson's employee has decided to move not just out of Salemtown, but out of the state of Tennessee, planning to go to Texas soon. Like many other residents of his neighborhood, he no longer felt welcome in the place he used to call home.

"A cultural shift happened," Anderson says. "Those who have lived there their entire lives or those who had grown up there were now seen as threats and as dangerous and as suspicious by those who were coming in because they were lower income. We felt the need to be in a neighborhood where our employees were comfortable and, as much of a bummer as it is to say, where the neighborhood would be comfortable with our employees. So that’s what brought us over into North Nashville. We wanted to be back in a place where there was a need for us — there was a desire for us — and we could limit as many barriers to employment as possible. Distance is one of those barriers. We want to be in the backyards of people we want to employ."

Proximity is at the heart of Anderson's mission — for his business, for himself, and for his family. Having spent his early life in what he describes as a "broadly white, upper-middle class" neighborhood in Nashville where there were "just enough people of color to allow [him] to think that everything was okay," he's grown to understand how deeply affected his city — and our larger society — is by racial inequality, and recognizes the place of privilege that the system affords him.

"I’m the fruit of a system that separated and segregated for hundreds of years for no other reason than because I’m white. I think, by and large, what people need to realize is that we live in a world that is still … especially in the South, we live in a world that is very intentionally segregated," he says. "It’s tough and heartbreaking, but I think that there is such a culture and knowledge gap and a worldview gap within our culture. Within America today, there’s such a broad difference of understanding how things are. It’s interesting in that, in my neighborhood, the way that people understand the world to work is completely different than the neighborhood that I grew up in. We’re striving to stay in the middle, as a business. I’m trying to be a good example of what it looks like to engage these things, but in a compelling way. Something that we’re trying to live out as a company is we are trying to address generational poverty that is tied to a history of systematic racism."

His belief, which fuels his work at Salemtown Board Co., is that "empathy and understanding, for the vast majority of us, those things will follow proximity." He takes steps every day to, as he describes it, "desegregate [his] life," and advocates for others to do the same.

"When we can move racial equality out of the realm of a hypothetical thing that should matter to us, to, ‘My friend is negatively affected by the system,’ that’s when we care," he says. "I can sit and have coffee and argue about higher level economics and whether we should elect Bernie Sanders or whether we should elect Rand Paul and not lose any sleep over it. But when I start talking about the systematic inequality in education, I can get teary really quickly because I’m not talking about a hypothetical thing. I can put names to these issues. I can see how these very real systems are affecting very real people in negative ways."

While Salemtown Board Co. has had its struggles, Anderson and his team are passionate about the work they do and the difference they've made in their own backyards.

"I get up every day because I love what I do. I don’t employ my employees because I feel guilty and feel bad for them," he says. "I only employ people that I feel excited about investing in and are excited about their futures. In the context of what we’re doing, we’re chasing what we’re really excited about. We get to take something that’s a hobby, turn it into a career and then use the things that we love — creating and skateboarding — and use them in such a way to provide opportunities for young men that otherwise might have had the opportunities."

Read more about a changing Nashville.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSave