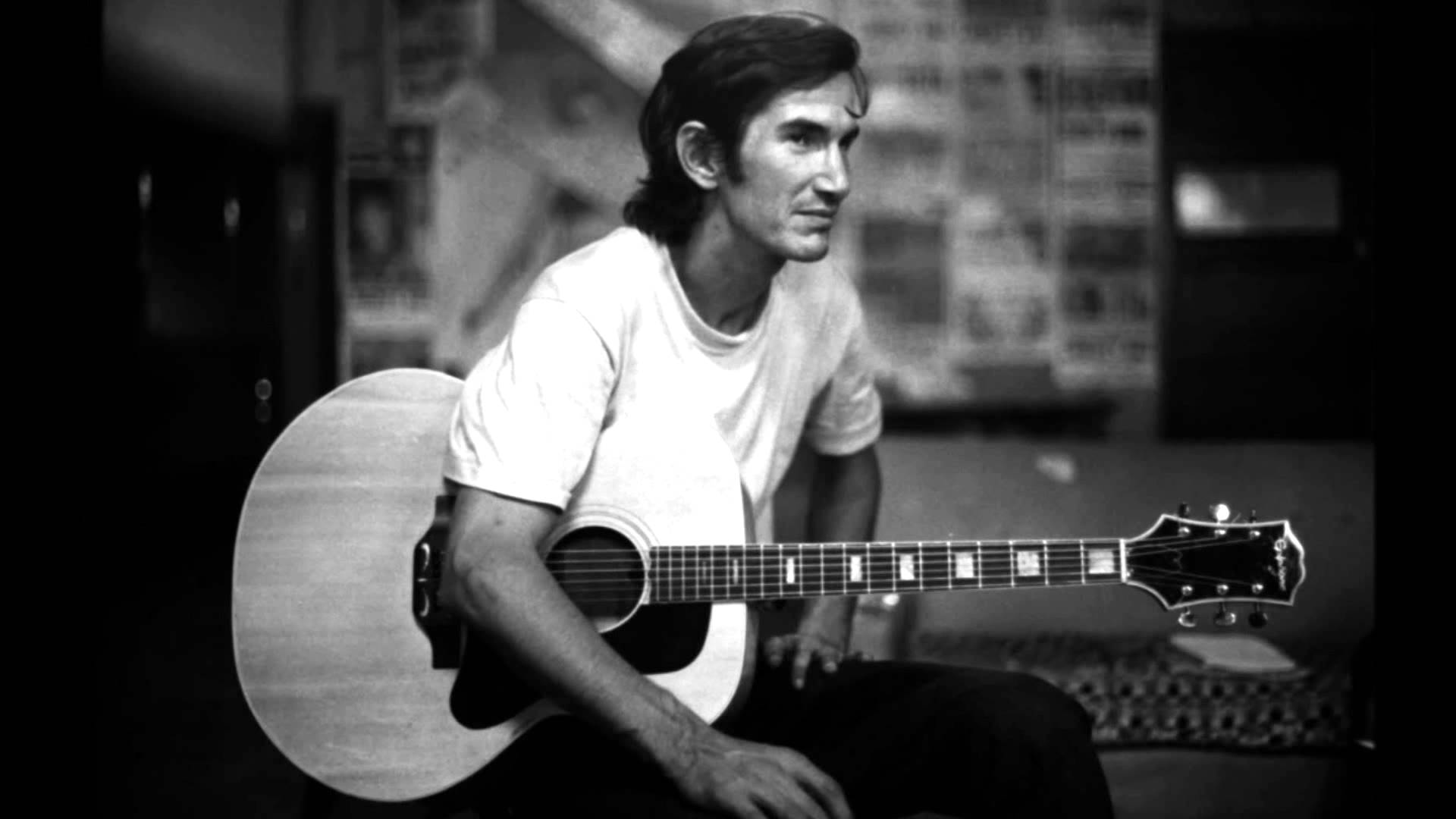

Georgia-born Brent Cobb doesn’t run from his roots. The singer/songwriter, a cousin to well-known Americana producer Dave Cobb, includes bits from his hometown and his upbringing throughout his latest full-length, Shine on Rainy Day. But this isn’t an album about a homebody or a good ol’ boy pining for old times. Rather, the record balances the comforts of homes and hometowns with the forward-moving momentum of life on the road. Songs like “Country Bound,” a number Brent borrowed from his father Patrick Cobb, is a homesick number, while “Traveling Poor Boy” shows off Cobb’s troubadour side. Shine on Rainy Day is a record for listeners with those same sensibilities, appealing to homesickness and travel and loss with an enduring message that urges its audience to see past current hardships.

Let’s start off with something basic: Can you tell me about growing up with music — your first experiences starting to write songs and also seeing songs written?

Yeah, I can still remember the first song I ever wrote … I don't know if you want to hear about that …

I do!

It was about rocks.

[Laughs]

It was walking around through the iron ore pits at my grandmother's house with my little sister. We were collecting iron ore rocks and it was a song about collecting rocks. It was "Millions and Billions and Jillions of Rocks," that was the name of my first song. [Laughs] I was 8 or 9. We just had picking parties — family picking parties and everybody played, and everybody wrote, and everybody sang.

Just to let you know what level it went to … In ’92, my dad had the opportunity — Doug Stone flew him to Nashville and took him around to a lot of publishers and with agents and record labels — and my dad was going to sign with Giant Records. He wound up not doing it because I was 7 and my sister was 3, and they kept talking about how much he would be gone on the road. So he decided to stay local, stay regional, and just play on weekends. I just always grew up around music. It was accepted as a trade and a career in my family.

“Country Bound” was the first song that I ever witnessed being written. I was 5, and we were in Cleveland, Ohio, for Christmas with my mama's folk. I was seeing snow for the first time out the window and then I would turn around and my dad and my uncle were writing "Country Bound." I remember them like it was yesterday writing "Country Bound." Every year on Thanksgiving, when my aunts and uncles would come into Georgia from Cleveland, we'd always play "Country Bound." I wanted to include it on this album because it's always been my favorite song. This album sort of has a theme of getting back home a little bit to it.

I really noticed that theme of getting back home. I know Dave Cobb produced this record, and you guys are related and you’d worked together before. How did this specific record come about?

After he moved to Nashville, we'd get together here and there and we always were just like, "Someday we'll do a record here." I toured for about four years — did 120 dates a year — and I stopped when I found out that I was fixin’ to have my first baby. I had a little baby girl, and so I took an indefinite amount of time off the road, and didn't know if I'd ever go back to making records as an artist or if I'd continue to just write songs.

In the middle of this break, Dave called me and he was making Southern Family. He said "Man, I'm putting together a concept album called Southern Family and I only thought it'd be appropriate for me to have my own Southern family be a part of the record, if you would write a song for it." And I was like, "Hell, yeah, I'll do that! That'd be great!" And so I wrote a song for Southern Family called "Down Home." I also helped … I was fortunate enough to write Miranda Lambert's song with her in "Sweet By and By."

When we were in the studio recording both of these songs, it just felt so good to be back in there with Dave. It just felt like home, and we knew that we had to make a record, but we didn't know that it was going to turn into all of this and I was going to do a deal with him or anything.

He produces like the way that I think I write. I write real spontaneously, and I write off of the muse of a moment. He's the same way as a producer. When he says something doesn't feel right, he doesn't mean technically it doesn't feel right; he means in his heart it doesn't feel right. And that's the way that I am when I write songs. It just magically happens.

Tell me a little bit more about writing songs. You’ve got the one song on the record, “Solving Problems,” that digs into the songwriting portion of your career. I think there is an interesting dynamic between this idea of being an artist versus being a songwriter when really, songwriting is an art.

I know! I never knew there was a difference! I thought they were all one and the same. But apparently, that's the first question that every publisher asks on Music Row. When I first went down there and I was checking on getting a publishing deal, they asked, "Are you more of a writer or are you more of an artist?" I just didn't know it was that different, really. And I guess it's because I like to do both — performing and writing — so much. Some people don't like the idea of going to Music Row and and co-writing in a publishing house, but I love it.

What is it that you like about it?

Well, I'll just tell you what my day is, so you can get an idea of what it's like: I get up at 6:30 with my baby and I drink coffee, and my wife gets home from work. I go in to write about 9 or so in the morning. I write till 3 o'clock in the afternoon with someone, whether it’s a co-writer or my publisher schedules a writer with me. While we write, we treat it like a regular job. It’s so cool to me because of the history of Music Row. If you read Willie Nelson's memoir — It's a Long Story is the name of it — he talks about writing "Hello Walls." That was the first song that he ever co-wrote on Music Row, and he just thought that it was such a strange feeling walking in there and not knowing a person and having to write these personal songs.

It is like that, but once you get used to it, it just becomes so much fun. It's just a bunch of collaboration … It's the best job in the world. I'm just glad to have it.

What made you decide to talk about it in “Solving Problems?”

I didn't have nothing else to write that day. [Laughs] That's the God's honest truth. I couldn't make anything else come, so … It's like, "Well, man, let's just write about exactly what we're doing right here." It's cool to be on Music Row writing songs about being on Music Row writing a song.

Speaking of co-writes, I would love to talk about "Shine on Rainy Day." That song appeared on Andrew Combs' record, and it says so much about the strength of the song that you guys can both make it your own. The title is different and I'd love to hear about why you decided to make that the title track of the album and what that song means specifically to you.

For me, that song meant a lot of things, really. It was coming from a lot of different places, so it's kind of hard to say. When you're going through a tough time, it takes a tough time to get to the end of that. When a thunderstorm comes up and the lightning strikes and it cleans the air, the next day the air is crisper, and the sky is bluer, and the trees are greener, and the grass is greener. After a storm passes, things are just better. They're new again. So that's what that meant for me, and it was from the last 10 years trying to pursue this career. Just like anything, it's got its ups and downs and it gets tough sometimes. So it's really about that for me.

I love that Andrew did it, as well. In the past, there'd be five or six different versions of the same song. I don't know how many different versions of "Sunday Morning Comin' Down" there are, but there are a ton of them that were all made back then. I love when a bunch of different artists do a song and I wish that would come back. I don't know why it doesn't exist as much anymore.

I named the album Shine on Rainy Day because I had given a pre-copy of the album to a close friend of mine, when he and his wife had just gone through a very personal family tragedy. That song was the one that really stuck out to him. It just really inspired me to name the album after it.

You write a lot about Georgia. I recognize landmarks and highways in the lyrics. How much of this was influenced by where you’re from and the idea of home?

I grew up in real rural Georgia, the southwest side of Georgia. It’s the surroundings, the wildlife, the pine trees, the red clay. It's the people down there. Growing up, you couldn't buy beer on Sundays. People are a little more cut off from the rest of the world. Their traditions and their ways — and mine, too — they're a little more old school. Everything's got a routine to it. It's just like reading a book that's been around forever. I don't know how to explain it. It's just something I've always noticed, too, and I've always studied. I guess it was a mixture of those surroundings and that environment, but then also with my family, too, being musical. I just love Georgia.

Photo credit: Don VanCleave