The first Canadian festival, a modest affair billed as a “Bluegrass Jamboree,” took place in August 1972. I was involved in its organization and presentation. Subsequently, the Jamboree grew into an annual festival that’s still running.

The Nova Scotia-based Downeast Bluegrass & Oldtime Music Society’s website reads:

The annual family friendly Nova Scotia Bluegrass and Oldtime Music festival is Canada’s oldest, and North America’s second oldest continuously running Bluegrass Festival, and is presented and hosted by the Downeast Bluegrass and Oldtime Music Society, a non-profit organization dedicated to the preservation and promotion of Bluegrass and Oldtime music in Eastern Canada.

Here’s how it happened.

By the summer of 1972 I had been living in Canada for four years, working as a professor of folklore and archivist in St. John’s, Newfoundland, at Memorial, the big provincial university.

Deeply immersed in bluegrass, I now stayed in touch with the music I’d left behind via bluegrass friends in the states, I read Bluegrass Unlimited every month, and I got County Sales‘ newsletters and bought new LPs from them by mail.

(Photo by Frank Godbey)

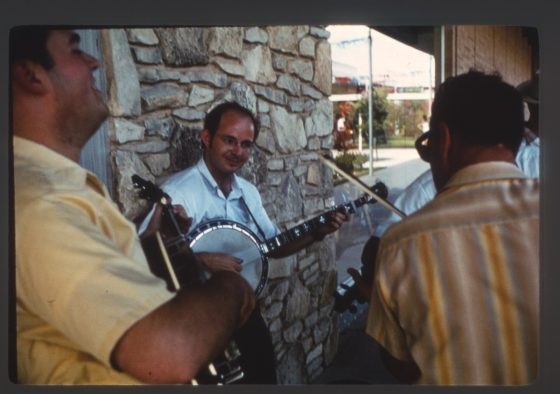

When I arrived in Newfoundland in September 1968, I’d just published my first academic article — on bluegrass — in the Journal of American Folklore. I’d been writing regularly for Bluegrass Unlimited. That past June, Bill Monroe had included me in a banjo workshop at his Blue Grass Festival in Bean Blossom, Indiana; and a few weeks before coming to St. John’s, I’d been at the Richland Hills fiddle contest near Dallas, Texas, jamming with Alan Munde, Sam Bush, and Byron Berline and the Stone Mountain Boys.

(b), Sam Bush (m), Byron Berline (f).

(Photo by David Stark)

During the late ’60s and early ’70s, bluegrass festivals were proliferating (I wrote about this in Bluegrass: A History, 305-339) and bluegrass was having success in the popular music business (I wrote about that too, 305-339).

By 1972 I was hearing at a distance about the adventures of my friends from the U.S. bluegrass festival scene. Alan and Sam had made a popular instrumental LP. Now Alan was picking banjo with Jimmy Martin and Sam was singing and playing mandolin with the Bluegrass Alliance. And Byron, working as a studio musician in Los Angeles, had recently recorded with The Rolling Stones.

As I continued to study and write about bluegrass, I maintained my musical calling, moonlighting in the local contemporary folk and pop music scene. It was several years before I met anyone in St. John’s who played or knew much about bluegrass.

In 1969, RCA Victor invited me to edit an album in their Vintage series titled Early Bluegrass. Aside from some Monroe LPs, this was the first historical bluegrass anthology. I signed its detailed historical liner notes with “Memorial University of Newfoundland” under my name. It got a good reception in the bluegrass world and introduced me to Canadian bluegrass record buyers.

In 1971 I signed a contract with the University of Illinois Press to write a volume on bluegrass history in their new Music in American Life series. It was a book that would take years to write, for I had catching up to do. Not only was I out of touch with the bluegrass scene I’d been in before immigrating, I also knew little about the bluegrass scenes in my new home.

Learning About Canadian Bluegrass

Even before immigrating to Canada, I knew it had bluegrass, thanks to Toronto’s Doug Benson, who put me on the mailing list of his magazine The Bluegrass Breakdown. The first issue had reached me in spring 1968 while I was still in Indiana. It told of bluegrass scenes in Ontario and Quebec.

En route to Newfoundland in September 1968, we entered eastern Canada via the Maritimes — the provinces of Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, and New Brunswick. Picking up our landed immigrant passes from Canadian Customs at the Maine border, we drove through New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, where, in Cape Breton, we caught the night ferry to Newfoundland.

During this trip I got my first taste of Canadian bluegrass in an Antigonish, Nova Scotia motel where we watched Don Messer’s Jubilee, a Halifax-produced CBC weekly TV show starring a fiddler who’d been recording and broadcasting nationally on radio since the 1930s and television later. Messer’s prime-time Jubilee was Canada’s second most-watched show, exceeded only by Hockey Night In Canada.

I was pleasantly surprised to see that Messer’s band included a five-string banjo played bluegrass style! To this immigrant’s eyes and ears, Messer was blending bluegrass into his country and old-time sound. Here’s his performance, taken from Jubilee footage, of “St. Anne’s Reel,” a popular Canadian fiddle tune:

The smiling banjo picker behind Messer was Vic Mullen, the youngest member of his band. Born in 1933 and raised in rural southwestern Nova Scotia, he had been working as a musician since his teens, playing with country bands in the Maritimes and Ontario.

In 1969, Mullen left Messer and began appearing with his own country band, The Hickorys, on another Halifax CBC weekly prime-time show, Country Time. There wasn’t much bluegrass on that show beyond Mullen’s occasional southern-style fiddle pieces.

Getting Acquainted

My first meeting with a Newfoundlander who shared my enthusiasm for bluegrass came early in April 1971 when I had a letter from record collector Michael Cohen of Grand Falls-Windsor.

By the time we met, Michael’s family owned six furniture stores in central Newfoundland. He’d grown up listening to country music on the radio and began collecting records. After attending university in Ottawa, where he’d heard lots of local and touring American and Canadian country music, he returned to Windsor to work in the family business, continue his collecting (he has all of Hank Snow’s recordings) and play in a country band.

He wrote me because he’d been told about me by a friend. “Early bluegrass and string bands … are my main interest,” he said, introducing himself and welcoming me to make tape copies of his rare records.

I wrote back inviting him to visit us on his next trip to St. John’s. This was the beginning of an enduring friendship. Through him I met others interested in bluegrass and Canadian country. The first was Fred Isenor of Lantz, Nova Scotia, a small community north of Halifax, who got my address from Michael and wrote me a few weeks later.

(Photo by David Stark)

Fred, Vic Mullen’s contemporary and friend, worked at the local brick factory, and had a music store in Lantz. He was a record collector, a Bluegrass Unlimited subscriber, and a musician. He played mandolin and bass in The Nova Scotia Playboys, which he described to me as an “authentic (non-electric) country” band. They had represented Nova Scotia at the 1967 Expo in Montreal.

Fred had purchased his mandolin, a 1920s Gibson F5, for $100 at a Halifax pawn shop in 1960. Only later did he learn that its label, signed by Lloyd Loar, meant that he now owned an instrument like that of Bill Monroe, who’d just been elected to Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame.

Our correspondence began with shared unsuccessful attempts to put together a Bill Monroe tour. I’d planned to speak with Monroe at a New England festival that summer. But the festival was cancelled; that plan fell through. In March 1972, Fred wrote of other plans:

There is a possibility of a one day bluegrass jamboree in Nova Scotia this summer. Not really a festival but if we can put it over it will be a start. Perhaps Michael has mentioned this to you. As you played with Bill Monroe and helped run Bean Blossom [I’d told Michael about this when we first met] I thought possibly you could offer some helpful suggestions, in other words some do’s and don’ts.

He explained that with a limited budget the event would have to utilize local talent.

Please do not mention this to anyone as definite … so far Vic Mullen and I just talked briefly about this and will be discussing it further on Monday night.

He asked if I’d be able to visit him and take part in the program.

I responded enthusiastically, calling the jamboree a festival, offering my suggestions, and saying I’d be driving through Nova Scotia in August and hoped to visit him then.

Meeting Vic Mullen

In June 1972, Country Time came to St. John’s to tape some shows. I asked Vic if he’d do an interview, explaining to him that I was working on a book about bluegrass. He agreed.

Still in his thirties, Vic had been playing country music professionally for a quarter century. He’d mastered instruments — mandolin, fiddle, guitar, five-string banjo — as needed, working on the road with a series of increasingly high-profile bands. Bluegrass chops were just one aspect of his professional tools — a flashy banjo piece, or southern-style hoedown fiddle as part of the show, that kind of thing. He’d worked with some bluegrass bands in Ontario, done TV, etc.

In the late fifties he started his own band, The Birch Mountain Boys. Working at first in southwestern Nova Scotia, he teamed up with Brent Williams and Harry Cromwell, young African Canadians from his home county, Digby. They played bluegrass in the Maritimes for several years before Brent and Harry started playing country and Vic joined Messer.

Now Mullen was fronting his own national CBC TV country music show. He liked bluegrass and enjoyed playing it, but as a bandleader he chose it rarely. Most people in his audiences didn’t know the word “bluegrass” when they heard it and even if they liked it, it was just nice country music to them. Bluegrass was a niche genre. It had enthusiastic fans and great performers, but they were in a minority.

Vic was supportive of his old friend Fred; he understood Fred’s enthusiasm. He knew about BU and the bluegrass festivals that were happening in the States, but he didn’t think the festivals were going to catch on in Canada. Of Canadian bluegrass fans, he said that:

Altogether in a group, there’d be a lot of people. But they’re spread out from coast to coast and particularly between here and Ontario … there wouldn’t be enough people for an audience in any one area, it’d be just too far for them to get there.

Still, he was planning to be at Fred’s Jamboree. In our interview, Vic had given me an insider’s introduction to the world of Canadian country music. From him I heard for the first time many names and facts that would become familiar to me later. I was encouraged that a musician of his caliber, experience, and reputation would be there.

A week after the interview, I wrote Fred and told him I’d be catching the ferry to Nova Scotia on August 1, driving to Lantz the next day and staying to get acquainted. I explained that this was just the start of a crowded trip for “some hurried field research on bluegrass music … in Ohio, Kentucky and Indiana.” I closed by mentioning that I’d had a pleasant experience interviewing Vic.

Fred’s reply came a few days later. He was looking forward to my visit, he said, and then, referring to my earlier letter, told me the event would be a jamboree — “outdoors, just one evening.” Referring to a nearby farmer who held dances in his barn, Fred explained:

John Moxom is building an outdoor stage as soon as his hay is made and it appears now that we will be holding it either Friday, August 4th or August 11th. All the local bluegrass musicians are willing to help and take a chance on it being a flop. We hope to find out if there is enough interest to try something bigger and better next year. I know you have a busy schedule but if August 4th turns out to be the date we would sure like to have you present.

By the end of July 1972, I was headed first to visit Fred in rural Nova Scotia. Then I’d drive to New England, stopping near the border at Woodstock, New Brunswick, to see Don Messer’s Jubilee perform at a county fair, and then going to Vermont where my family was vacationing. After a short rest I’d be heading for West Virginia to join my photographer friend Carl Fleischhauer on the trip we described in Bluegrass Odyssey.

On August 1, I headed for the Canadian National ferry terminal in Argentia, Newfoundland, ready to sail west for some bluegrass.

Rosenberg is an author, scholar, historian, banjo player, Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame inductee, and co-chair of the IBMA Foundation’s Arnold Shultz Fund.

Photo of Neil V. Rosenberg by Terri Thomson Rosenberg, all other photos by Neil V. Rosenberg.

Edited by Justin Hiltner