Wilma Lee Cooper, who died in 2011 at age 90, is being inducted into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame this month. Many of her fans, friends and followers say it’s about time.

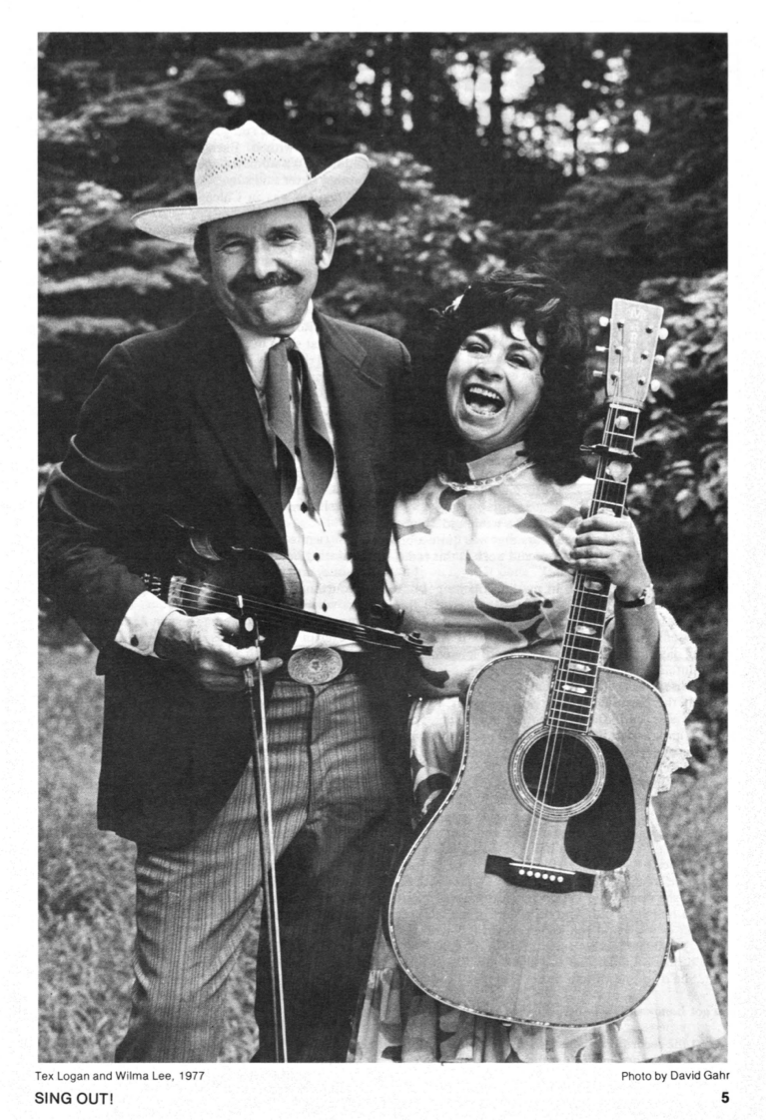

A snapshot of Wilma Lee. Wilma Leigh (later changed to “Lee”) Leary, was born in West Virginia in 1921. Her first performances were as a young girl in the family band. Her last performance as a band leader was in 2001 at the age of 80, when she had a stroke while singing at the Grand Ole Opry. Determined to finish the song, she was helped off stage to a standing ovation.

Between these times, this tiny woman dressed in home-made ruffled dresses and high heels impressed everyone she encountered in the music world.

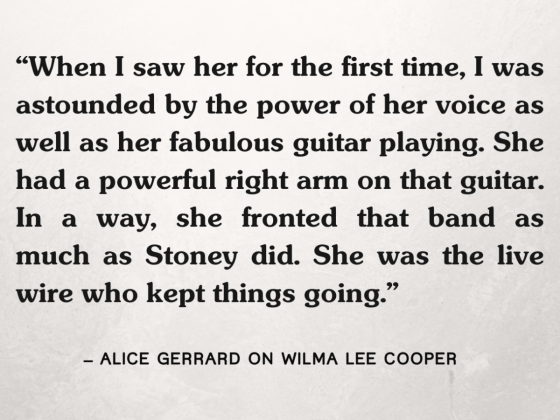

She had a powerful voice and was an equally powerful guitar player. With her inherent smarts (she skipped several grades) and business degree, she successfully navigated the music industry and kept all the band’s books, first with her husband, Dale Troy “Stoney” Cooper, and then on her own after Stoney’s death.

She traveled with a sewing machine and a coffee maker. After every tour, she would wash all her stage clothes and spend 45 minutes ironing each dress.

She also drove the band bus and fixed her family’s television sets. She was a kind and generous boss, a nurturing mother, an ethical and caring woman and a force of nature on stage.

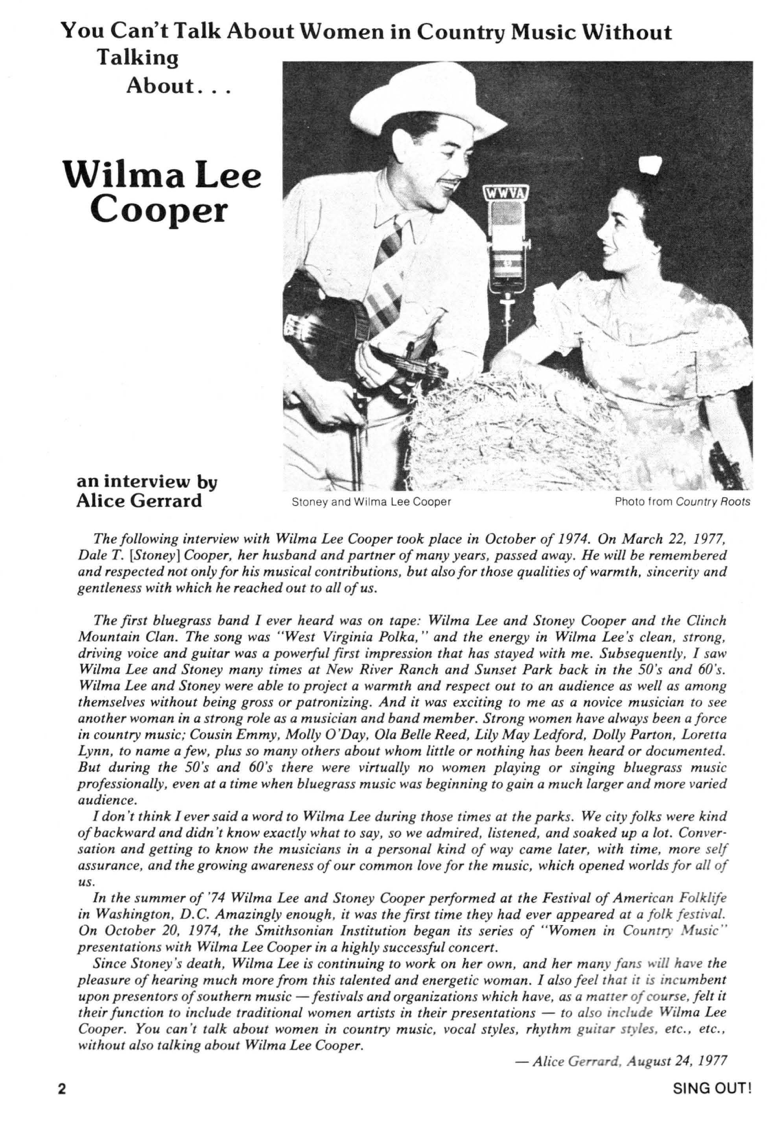

(Above, read an article on Wilma Lee Cooper published in 1977 in Sing Out! written by Alice Gerrard)

From church socials to radio. Reviewing Wilma Lee Cooper’s musical life is an immersion course in the evolution of country and bluegrass music. The Leary Family Band – Wilma Lee’s parents, plus Wilma Lee, her two sisters, and a fiddle-playing uncle – started as a local gospel group. The girls later incorporated secular music sets.

Their prize for winning a statewide contest was the chance to perform at the National Folk Festival in Washington, D.C. A stop at WSVA in Harrisonburg, Virginia, on the way home brought a job offer – and big changes. In one day, the Leary Family went from a local ensemble to professionals with a show of their own. And, when their fiddling uncle returned to his teaching job, the family recruited a young fiddler then called “Smiley” Cooper. (Radio listeners voted for the new name, “Stoney,” to avoid a conflict with a state yodeling champion called Smiley).

Soon, the beautiful oldest daughter and the movie-star handsome fiddler were singing duets with the band. They married in 1941.

Foregoing music to raise their daughter, Carol Lee, in one place was short-lived. Wilma Lee is quoted in Bear Family liner notes as saying, “I was goin’ nuts at home… Stoney wasn’t happy… and it was awful hard to settle down that way.”

On to the Grand Ole Opry. Plunging back into performing, Stoney and Wilma Lee followed the common path of moving from radio station to radio station. They hired back-up players, eventually settling on the band name, “Clinch Mountain Clan.”

In a 2023 Bluegrass Unlimited article, Jack Bernhardt referred to “Stoney’s old-time/bluegrass fiddle and Wilma Lee’s propulsive rhythm guitar and soul-stirring vocals.” Stoney also sang harmonies.

Their 1947 move to Wheeling, West Virginia, and the WWVA Jamboree, broadcast on a 50,000 watt station, propelled the Coopers into the national spotlight. By the mid-1950s, they were charting high on Billboard. Within a year of their 1956 hit record, “Cheated Too,” they joined the Grand Ole Opry. They had seven hit records by 1961, with some of Nashville’s top writers, like Don Gibson and Boudleaux Bryant, writing for them – as well as songs written by Wilma and Stoney, themselves. While the recording business was moving away from what had been called “hillbilly music,” the Grand Ole Opry continued to welcome the eclectic range of country music, from Grandpa Jones and Bill Monroe to “Nashville Sound” crooners.

Dan Rogers, Vice President and Executive Producer of the Grand Ole Opry, said, “It was this cavalcade of great artists, all doing something similar, but also all doing something with their own stamps and styles. It didn’t need characterization. It was just, ‘This is Wilma Lee and Stoney.’ It might have been one of those songs that took them to the Top 10 of the country charts, or it may have been an instrumental or a gospel piece.”

Over time, the Coopers found themselves in conflict with the Nashville labels. Wilma Lee said a producer denied her request to record “I Dreamed of a Hillbilly Heaven,” claiming no one would buy it. It later became a huge hit for Tex Ritter. And they wanted her to record songs she would never perform.

The welcoming bluegrass world. While country radio was pushing away mountain music, new audiences were inviting the Coopers in. Folk and bluegrass fans loved their traditional sounds, as well as their stellar musicianship.

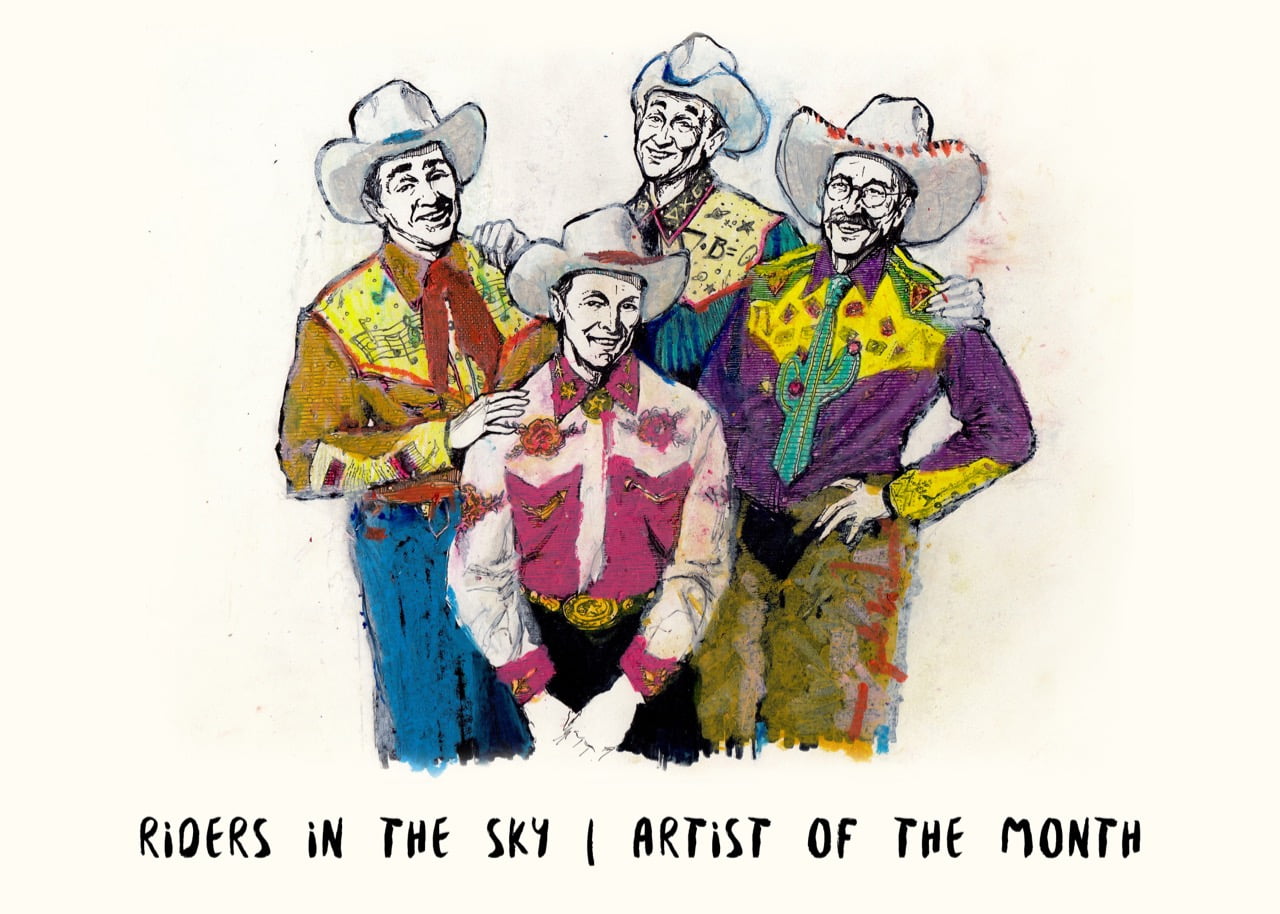

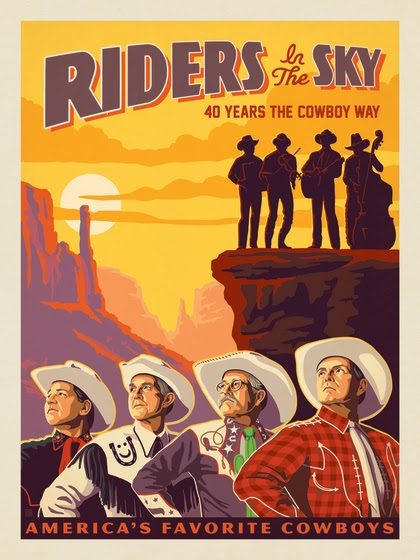

The Clinch Mountain Clan attracted top sidemen. To name a few, Butch Robins, Vic Jordan and Tater Tate went on to play for Bill Monroe, and Jimmy D. Brock later joined the Osborne’s. Dobro master Gene Wooten was in Wilma Lee’s band, as was Woody Paul, shortly before forming Riders In the Sky, and Terry Smith, now of the Grascals.

Marty Lanham (musician, luthier and a founder of the Station Inn) had just moved to Nashville, where he was befriended by Wilma Lee’s sisters, Jeraldine (Jerry) Jonson and Peggy Gayle. They told him the Coopers were looking for a bass player. So, he borrowed a bass, took some lessons – and become part of the Clinch Mountain Clan three weeks later.

The Coopers always gave their audiences what they expected. Lanham said, “Bill Carter would play Dobro and electric guitar, and Mike Lattimore would play either banjo or drums. At a bluegrass festival, they would use the bluegrass instrumentation and then switch over to electric guitar and drums,” at a country booking.

In 1974, the Smithsonian Institution dubbed Wilma Lee, “The First Lady of Bluegrass.” In 1976, Rounder Records – dedicated to promoting roots music – invited Stoney and Wilma Lee to record. Marian Leighton Levy, a Rounder co-founder, remembered Stoney as “tall, dark and handsome,” with an Errol Flynn aura, while Wilma Lee “was outgoing and friendly, in a low-key and down home way. She looked and played the part of a real professional, and yet at the same time she was warm and made you feel welcome.” Wilma Lee also worked with Rounder to select material, and she seemed to be “the business person in the group and in the family,” Levy remembers.

Wilma Lee takes the lead. Wilma Lee was 56 when Stoney died in 1977. She wasn’t ready to sit back and put her feet up. She reassembled a band, which after some initial shuffling included Gene Wooten; Stan (Stanjo) Brown, who later played with Bill Monroe; Gary Bailey; and Woody Paul. (Wilma Lee continued her preference for an electric bass, even after getting pushback from bluegrass critics who hated it on recordings.)

Their first year, the band traveled 110,000 miles, playing about 140 gigs. On one 3,600 mile week-long trip, Wilma Lee drove about one-third of the time.

Brown remembers that Wilma Lee embraced the bluegrass world as it was embracing her. “She was doing the same material (as when Stoney was alive), but it was approached a whole different way. Her guitar really drove the rhythm and the energy in the band. And her voice… it set the timing… it was so precise. I had never played with anybody up to that point who had that much energy and drive.”

And she always connected at an emotional level. She would be sobbing by the end of the song “A Daisy a Day,” about a man who leaves flowers on his wife’s grave. “It was really sincere. There was nothing theatrical about her,” Brown said.

She told Alice Gerrard for Sing Out!, “…I see the story a-happening while I’m singing the song… I guess I’m one that likes what you call your heart and story songs. They tell a story – you’ve got to believe it.”

Rogers of the Opry said, “I always think of her music as pure, and I think that her heart was the same. I don’t think she could have been any other way if she’d tried.”

Wilma Lee continued to record, as well as perform, until her stroke in 2001. In 2010, she appeared on stage once more at the Opry to thank her fans for their years of support.

Wilma Lee and the world of bluegrass. Stoney and Wilma Lee were stars, no matter what genre they were playing. Their partnership was one of a kind. And Wilma – as a singer, as a guitar player, as a fireball on stage and a huge heart off stage – has left a powerful legacy.

In 1994, the International Bluegrass Music Association presented Wilma Lee with its Award of Merit. This year, she will receive its highest honor, induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.

Rounder’s Levy said, “There are very few women of her generation in the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame.” (In fact,

only eight of the current 70 inductees are women or have women members.) And Levy believes Wilma Lee clearly belongs there.

“In terms of being on the Grand Ole Opry, making lots of records, having a substantial career… the uniqueness of her vocal style, playing guitar when most women in bands weren’t playing guitars or instruments… She was a bandleader and a featured voice, face and name, right up there in her own right,” Levy said.

Ken Irwin, another Rounder co-founder, said, “She was an energy source that people didn’t see very often… She would put it all out there. She brought not only the tunes, but the sensibility, of the old-time music that she grew up with, and that she didn’t change.”

Gerrard said the popular female folk revival singers at the time, like Joan Baez and Judy Collins, sounded high and sweet. But Wilma Lee’s voice – like Molly O’Day’s and Ola Belle Reed’s – had grit and strength. “They weren’t holding back. They were letting go – putting their voices out there.” That’s what Gerrard was striving for and what made her duets with Hazel Dickens so compelling.

Andrea Roberts, principal of the Andrea Roberts Agency, was an adolescent when she first saw Wilma Lee perform. “She carried herself so professionally, looked like a star – and backed it up with talent and business leadership. She was a dynamic vocalist – a big, booming voice – and she played the guitar like she meant it! She was not timid… and that left an indelible mark on me even when I didn’t realize it was happening.

“Not until I started my own band as a 21-year-old woman did I realize the significance of Wilma Lee’s role as band leader and front person. At that point in my own career, Wilma Lee’s accomplishments became very important to me, and I looked to her as a role model for persevering in a male-dominated business.”

A daughter’s thoughts. Carol Lee Cooper, Stoney and Wilma Lee’s daughter, who first sang on stage with her parents at age two, has carried on the family musical tradition. As an adult, she joined her parents’ show at the Opry. Eventually, she became a Nashville legend as the long-time leader of the Carol Lee Singers, the back-up vocalists at the Grand Ole Opry. A great vocalist, she was Conway Twitty’s favorite harmony partner.

Carol Lee is proud that her parents’ work is recorded in the Library of Congress and the Smithsonian Institution. Of her mother’s induction into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame, Carol Lee said, “She would be so honored to know that.”

Author’s Note: Many excellent accounts of Wilma Lee’s life and career have been written. A great starting place for anything you want to know about women in bluegrass is Murphy Hicks Henry’s Pretty Good for a Girl. Some other good sources, in addition to the Gerrard interview mentioned above, are Bluegrass Unlimited and liner notes from a Bear Family compilation.

Editor’s Note: “You Can’t Talk About Women in Country Music Without Talking About… Wilma Lee Cooper” by Alice Gerrard (SING OUT! Volume 26 Issue 2, 1977) appears with permission; courtesy of Mark Moss and SING OUT!

Photo Credit: David Gahr, from SING OUT! Volume 26 Issue 2, 1977

That, Slim says, was his introduction to the music of the Sons of the Pioneers, the Western swing-and-harmony group that featured Nolan and cowboy-star-to-be Roy Rogers. Soon, with the addition of Windy Bill Collins, they dedicated themselves to the traditions of the singing cowboys — Gene Autry, Tex Ritter, Rogers of course — and the Western ideal. Well, at least for one show.

That, Slim says, was his introduction to the music of the Sons of the Pioneers, the Western swing-and-harmony group that featured Nolan and cowboy-star-to-be Roy Rogers. Soon, with the addition of Windy Bill Collins, they dedicated themselves to the traditions of the singing cowboys — Gene Autry, Tex Ritter, Rogers of course — and the Western ideal. Well, at least for one show.