Releasing a new album is stressful enough for most artists, but releasing an album, a documentary, and a book almost simultaneously – while singing and dancing in a Broadway musical? That sounds crazy even to Ani DiFranco, who released her 23rd album, Unprecedented Sh!t, in May, while performing as Persephone in Hadestown, reprising the role she sang on the same-titled Anais Mitchell album that became the folk opera. (The album was released in 2010 on DiFranco’s Righteous Babe Records label; the show opened on Broadway in 2019 and won eight Tony Awards, including Best Musical and Best Original Score.) DiFranco wrapped her nearly five-month acting debut on June 30, just after performing at the Tribeca Film Festival premiere of director Dana Flora’s documentary, 1-800-ON-HER-OWN, filmed as DiFranco recorded her 2021 album, Revolutionary Love.

On August 27, DiFranco will release her second children’s book, the timely and inspiring lyrical narrative, Show Up and Vote, illustrated by Rachelle Baker. (Her first, The Knowing, was released in 2023.) For most of these endeavors, including Unprecedented Sh!t – only her second album produced by someone else (BJ Burton) – DiFranco did something she’s not used to: giving up control.

Who decides to be in a play, release an album and a book and have a documentary premiere at the same time?

Ani DiFranco: No one would decide that. That’s fate just laughing at me, just fucking with me. But it’s exciting. It’s exhausting. And my hamstrings may or may not hold me up through it all. [Laughs] But I wouldn’t be anywhere else.

Obviously, you’ve spent time in front of audiences. What’s different about doing it in a musical?

I’ve realized that performance has, at least for me, two big components. One is improvisational; it’s of the moment. It’s interactive. The other is putting on the show. I’ve always leaned into the interaction and improvisation. This is very much leaning in the other direction. Doing the same shit every night, eight times a week, for months, is a whole other approach. … What I think I love most about this super unique experience, besides the work itself – Hadestown is such an epic work, and I couldn’t think more highly of it – I’ve never done something where it’s such a group effort. I really have been amazed by [the] collective experience. Like we all became one organism, sort of this collective energy field.

Do you think you would get involved in another production like this?

I’m pretty open to anything. I’m most enamored by the new and terrifying, so I have no idea.

I would think a documentary is exciting, too.

Yeah. Yes …

You don’t sound so sure.

I’m just going with exciting as the adjective. [Laughs] For me, it’s very disconcerting.

In what way?

I actually haven’t seen it and I’m not sure if I will. It’s a lot, to show yourself.

That’s got to be a challenge. But you have led what I consider to be a singular life and have had a really impactful career. It seems like it would make sense to put that onscreen.

It’s not a career-defining, expansive retrospective. Of course, there’s some historical context. But it’s just a walk in the shoes of a woman who’s trying to be an artist in the world, and also a mother and have a relationship and be accountable to everyone that wants her to be at any given moment.

Let’s talk about the voting book. I’m so charmed by the concept, because it’s such an important one to teach. What inspired you to do that?

Exactly what you said. I feel like young people being inspired to vote in this country, in this moment, is the difference between having a democracy tomorrow and not. So when I was invited to make a book for children, I thought, “Hey, maybe I’ll try to talk to some future voters.” It’s from a kid’s point of view about going to vote with her mom. The book is a tool with which parents can engage their kids about voting.

I’m somebody who takes my kids with me to vote so that they see it modeled, so that they understand it as a part of being grown and a member of a society. But even more than a teaching tool, I hope that it will inspire kids, that it will get them excited about this thing that they get to do when they’re grown up, because they’re part of a democracy. It’s a really important, empowering, profound thing that connects them to everybody else, and is a way that we take care of each other, a way that we express our love for each other, and all of these really cool things. I guess I most hope that it lights a fire in a kid.

That brings me to the album. I noticed that “The Thing at Hand” and “The Knowing” seem to share similar concepts, but the latter one apparently was describing the ideas to a child. Is there a connection?

They are very related, but “The Knowing,” I wrote specifically to a child. When I was faced with making my first children’s book, I was having a hard time, and the only way I made it through was to pick up my guitar and make a song that was also a book. And “The Thing at Hand,” those themes of identity and ego, and the vast realms that exist beneath that or beyond it, are themes that run through the record.

I totally caught that, and I loved the lyric, “I defy being defined”; that sums up a lot of your career – and your life. How hard has it been to maintain that stance in a society and music industry that seem to be all about definitions, and judging based on them?

It’s been really hard, every step of the way. People want to define and describe you in very finite terms, and they’re often very reductive. Holding onto a sense of myself as this ever-changing field of infinite possibility, so to speak, is a hard thing to do. There are pressures from every direction to be something very concrete, that thing that this person or that person or the other wants you to be or insists that you are. It’s been a real dance of negotiating that all the way along.

What do you do when it gets really frustrating?

I’ve had to just develop this – I mean, I’m as thin-skinned as the next guy, when it comes right down to it. I am as lost in seeking affirmation from the world around me instead of from inside myself as the next guy, so it’s a constant challenge to go beyond all of that and to keep yourself at a distance, no matter what the world is saying about you. I’ve learned that you can’t rely on the world to tell you that you’re worthy and you’re good and you’re great and you’re wonderful, which sometimes it does, because then when it turns around and says you’re unworthy, you’re terrible, you’re horrible, you’re a sham, your whole premise of yourself comes crumbling down. So it’s still a challenge that I am trying to rise to, to self-love. The older I get, the more I believe that the ways that we harm each other all come home to our lack of self-love. So it’s not some kind of trite endeavor; it’s not self-centered or indulgent. It is extremely important to peace on earth that we learn to find our inherent worthiness within ourselves in order that we not turn our self-hatred on each other.

Back to the concepts you address in these songs. “New Bible” sounds almost like a manifesto; there’s so much to unpack there. In other songs, you just allude to an idea; for instance, in “Baby Roe,” you say, “I think we might be wrong about all of that,” which raises the question, wrong about what?

That’s another song that is interrelated on the theme of ego and identity; it’s … stepping back from this debate about abortion and reproductive freedom and going, this is ridiculous. Like, projecting your ego onto a potential human; it’s like, I am a being of light. I am consciousness and that’s what you are. And this is one of many, many lives and manifestations of this unified field of consciousness that unites us all, that we are coming from and returning to infinitely, that we are all one within. This idea that consciousness need be born right now, into this exact body, in order to be manifesting, is really silly. The whole premise of forced reproduction is based in this very stunted understanding of what we are and what life is and what death is. I think a lot of the traps that we fall into that are entrapping us more and more, sociopolitically, environmentally – it’s all ego-based delusion.

In many of these songs, you sing so sweetly, and yet there’s these undertones, like in “More or Less Free.” I was surprised to read that was about somebody in prison; I thought of it as possibly directed to oppressors.

“More or Less Free” is intentionally open-ended, but yes, it’s written from within prison walls, as a free person inside a prison, visiting and having very human moments and connections with people who live in cages all the time. But it’s a tricky business to talk about songs and what is this about and what is that about? I hate doing that, because songs are supposed to reach you the way they reach you and you’re supposed to hear what you hear, or not. And that’s not for me to say, really. They’re about what you decide they are.

But you know what I’m saying. Technically, that’s where it comes from, but it is very much about being born into a society, that dichotomy of – we are all born free, as my friend Utah Phillips would say, and then you wait for somebody to come along and try to take away that freedom. He always said the degree to which you resist is the degree to which you are free. So yeah, we are all born free, and yet, we’re not. That’s all that it’s about.

What was different about doing an album with somebody else calling the shots?

Everything of this particular record and process was unique. The remote thing, for one, which is just how it worked out. He and I would have loved to have spent endless hours in a room together vibing off each other, but we did it interacting through many levels of machines. In retrospect, that’s maybe exactly apropos for a record where I was really trying to bring the machines in. BJ, of course, is the one with the machines and the facility to be intuitive and creative with them, but we sort of worked vicariously with each other.

Because I was not in the room with him, I couldn’t say, “Ooh, a little to the left. Oh, a little louder.” It was like, I record the songs, he fucks with them royally, and what comes back is – I mean, we had a little back and forth, but really, it was overwhelmingly a process of giving over. Just saying yes to his artistry, like he was saying yes to mine. I was not prepared to do [that] at 20 or 30 or 40, and with album one or six or 10. But this is album 23. I’m 53 years old, and I’m more than ready to say yes and really delegate.

People have gone back and redone previous albums. Maybe 10 years from now, you might decide that you want to redo it.

Well, I’ve been in this music game and song-making game for 30-plus years, and one thing that I’ve learned from experience is that songs have long lives. And, that even when I was in charge and doing everything “the way I thought it should be done,” which was most of those other records, I don’t necessarily “get it right,” or the album version is not the definitive version of any song of mine, necessarily. In fact, I have no memory of making any of them. And sometimes when I hear them, I’m like, “Whoa, what?” because the song as it’s lived onstage and in the world is not necessarily that moment. When I had misgivings about BJ’s tendency to turn my guitar into some other sound, or eliminate it altogether, or sort of deconstruct what I sent him or something, I would think, “Whoa, is this cool?” And then I was thinking, “Well, who cares? That’s just how it sounds on this little piece of vinyl.” The song, it’s like a snapshot of a human; the human has many faces.

I love the line in “Unprecedented Sh!t,” “the bigger the heart, the more it bleeds.” But it also sounds like there’s an attempt to ignore that [i.e., “I got a lot of heart/ But I can’t afford to let it bleed”]. Sometimes, for example, with animal rescue, I have to stop myself from reading another story about this poor …

Oh, yeah. Dude. That’s all I’m talking about there, is how much we have to numb ourselves to survive being surrounded by pain and suffering and feeling helpless, if not being helpless, to stop it.

It’s a shame that we have to numb ourselves, but on the other hand, do you ever feel like that character in The Green Mile, where it’s just all going into you, and it’s too much to hold sometimes?

Yes, very much. I think anybody whose heart is not dead inside their chest is trying to deal with that.

That’s what I got from “New Bible,” too. There are some really pessimistic statements in there, but there’s also some real optimistic ones, a sense of, yeah, you can let this stuff overwhelm you, or you can look for ways to do something. That, to me, is a really good thing to put out there.

Yeah. Which brings us back around to the children’s book. The tools of nonviolent revolution are right there in our pocket, actually. What do you know? What do you know?

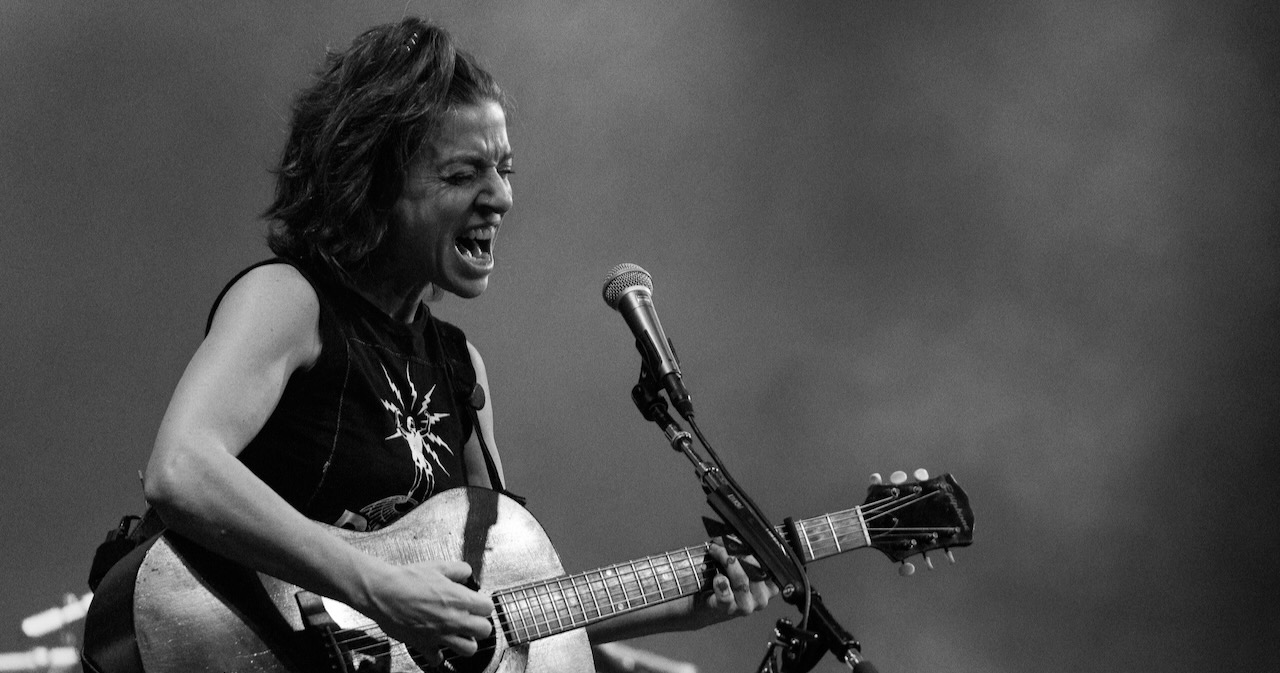

Photo Credit: Anthony Mulcahy