Fifty years ago, the Byrds set out on an ambitious path to deeper explore the country music they had flirted with on previous records with Sweetheart of the Rodeo. In addition to introducing Gram Parsons to a larger audience, it was the first country-rock record to be recorded by an established rock act. The record continues to open the eyes of new generations to country music. Recorded in March of 1968 in Nashville, Tennessee, and April of the same year in Los Angeles, California, the original record utilized the amazing steel guitar talents of Lloyd Green (Nashville) and Jay Dee Maness (L.A.), both established session musicians. The freshness of their playing added not only an authenticity to the sessions, but opened the eyes of a whole new audience to the sound of the pedal steel guitar.

Now, 50 years later, the original steel guitarists have reunited to make a stunning instrumental tribute to this ground-breaking record. Over the intervening decades, the two masters have played on countless songs. Here are some of their favorites.

LLOYD GREEN

Warner Mack — “The Bridge Washed Out”

Owen Bradley, the producer, did not want to use me since he didn’t know me nor my capabilities. He insisted on Pete Drake, who Warner said could not possibly play this new idea and sound I had discovered. Owen reluctantly let me be on the session, and it became Warner Mack’s first and only number one record, for which Owen Bradley then took credit, telling people that he knew they had a hit with my sound on that record. It was my career-launching recording.

Tammy Wynette — “D-I-V-O-R-C-E”

Producer Billy Sherrill heard me doodling with a new sound I had discovered, recognized its uniqueness, and told me that was going to be the signature of the song. It was and quickly became a number one record for Tammy, where I introduced the last remaining missing component of the E9th commercial tuning heard on most records which had remained unknown — the E to F pedal change. It now is part of our tuning on all steel guitars which use the commercial E9th neck.

Freddie Hart — “Easy Loving”

George Richey had gotten in an argument with Freddie about how we should record this song and, wisely, went outside for a smoke and to cool off. So Charlie McCoy, Billy Sanford, and I said, “Let’s cut this damn thing,” which we did in two takes. Richey came back in and asked if we were ready to cut it, but I told him we already had. He listened with a bored look on his face and said, “Sounds okay, next song.” Little did he know we had just cut Freddie’s career song which sold around two million copies and became a number one, and also became one of only three records to ever become the Country Music Association’s Song of the Year two years in a row, in 1971 and 1972.

Gene Watson — “Farewell Party”

We had recorded Gene’s new Capitol album but lacked one more song to complete the music. Having but 10 minutes left in the session, both Gene and his producer, Russ Reeder, came over to me and asked if I would just do an intro and a solo in the middle real quickly so they could finish the album and not have to pay the musicians overtime. I did. We cut the song in one take and left for our next sessions. While not becoming a number one record for Gene, it quickly became his most famous recording and he even named his band Farewell Party. The song became a cult favorite among steel guitar players around the world.

Alan Jackson — “Remember When”

Keith Stegall, Alan’s producer, called me when he heard I was coming out of a 15-year retirement to again record, asking me to cut with Alan Jackson. It was my first time back in the recording studio. On the session, Alan told me his favorite steel solo of all time was what I played on “Farewell Party.” He asked me to give him another “Farewell Party” solo. The song, of course, went to number one, like all of Alan’s records and, ironically, became the last major country music record with a significant 16-bar solo. Steel is no longer featured on most big recordings.

Leslie Tom — “Hey Good Lookin'”

“Hey, Good Lookin'” is a Hank Williams song I’ve played since the age of 13 or 14 in the bars and clubs in Mobile, Alabama. I can still play it exactly like Don Helms recorded it back on non-pedal steel guitar in 1951 with Hank. But … I only honored him with some key phrases on this modern Leslie Tom recording. My entire recording career has been built around creating sounds, not imitating others. Leslie’s version, while also honoring Hank, has a bit more swing and sizzle to it, so that’s the direction I went. It is really good, and I am honored to get to record with such a talented, beautiful lady. Leslie sings it with fervor and an obvious love for Hank Williams’ music.

JAY DEE MANESS

Gram Parsons — “Blue Eyes”

I got a call to work on an album called International Submarine Band with Gram Parsons. When I got to the studio, I found out that Glen Campbell would be playing acoustic rhythm guitar. This was my first encounter with both Gram and Glen. In addition to myself on steel, the album had Jon Corneal on drums, Joe Osborn on bass, and Earl Ball on piano. This album was produced by Suzi Jane Hokom. The album was eventually released in 1968, after the group ceased to exist. Some might say this was a precursor to the Sweetheart of the Rodeo album.

Ray Stevens — “Misty”

In 1974, I was lucky enough to record in Nashville on a song called “Misty” with Ray Stevens. Shortly after the session, I moved my family back to Los Angeles. One day, Ray called and said he had been nominated for a Grammy for “Misty,” and asked if I wanted to play on the Grammy Awards. Of course, I said yes. I was thrilled to get to play the Grammys on national TV with Ray Stevens. During rehearsal, all went well. Once it was our turn to be on stage — live — and it came time for my “solo,” I broke the third string on my steel guitar. This string is very important to the sound of the solo so, on national TV, and I had to “fake” it. This was a very embarrassing moment.

Eddie Rabbit — “Every Which Way but Loose”

In 1978, I received a call to do the soundtrack and had a bit part in the movie Every Which Way but Loose, which was produced by Clint Eastwood. All the bar scenes were being filmed at the Palomino Club, so Clint decided to use the house band in the movie. I had already received the call to do the soundtrack and to play with Eddie Rabbit on the title song and to play on Mel Tillis’s “Send Me Down to Tucson.” Soon enough, I was called to do the Any Which Way You Can soundtrack, too. In addition to the soundtrack, I was able to play with Shelly West and David Frizzell on “You’re the Reason God Made Oklahoma.” I also had the opportunity to work on “Bar Room Buddies,” sung by Clint Eastwood and Fats Domino.

Anne Murray — “Could I Have This Dance”

I had the privilege of working with Anne Murray on her hit song “Could I Have This Dance” which was produced by Jim Ed Norman. “Could I Have This Dance” was also in the Urban Cowboy movie and soundtrack. Later on, I got a call late one evening from Jim Ed Norman asking if I could come over to his studio after my gig at the world famous Palomino Club. He said, “I have a record for you.” I thought it was a copy of the album which had the tune on it. When I got to the studio, he presented me with a platinum record of “Could I Have This Dance” from the Let’s Keep It That Way album to hang on my wall. This was the first of many albums from various artists that I now have on my wall.

Eric Clapton — “Tears in Heaven”

When I got to the studio to record with Eric Clapton, I was told Eric was not feeling well and could I come back the next day. The next day, I came back and started recording. We took all day to record Eric’s song called “Tears in Heaven.” I was packing up my steel guitar, when Eric came out into the studio and said, “I would like you to play the solo.” That’s when I got scared. I played the solo (melody) on the steel and, after I left, Eric put the harmony part on top of my melody. “Tears in Heaven” became a number one hit for him. I feel very privileged to have played on it.

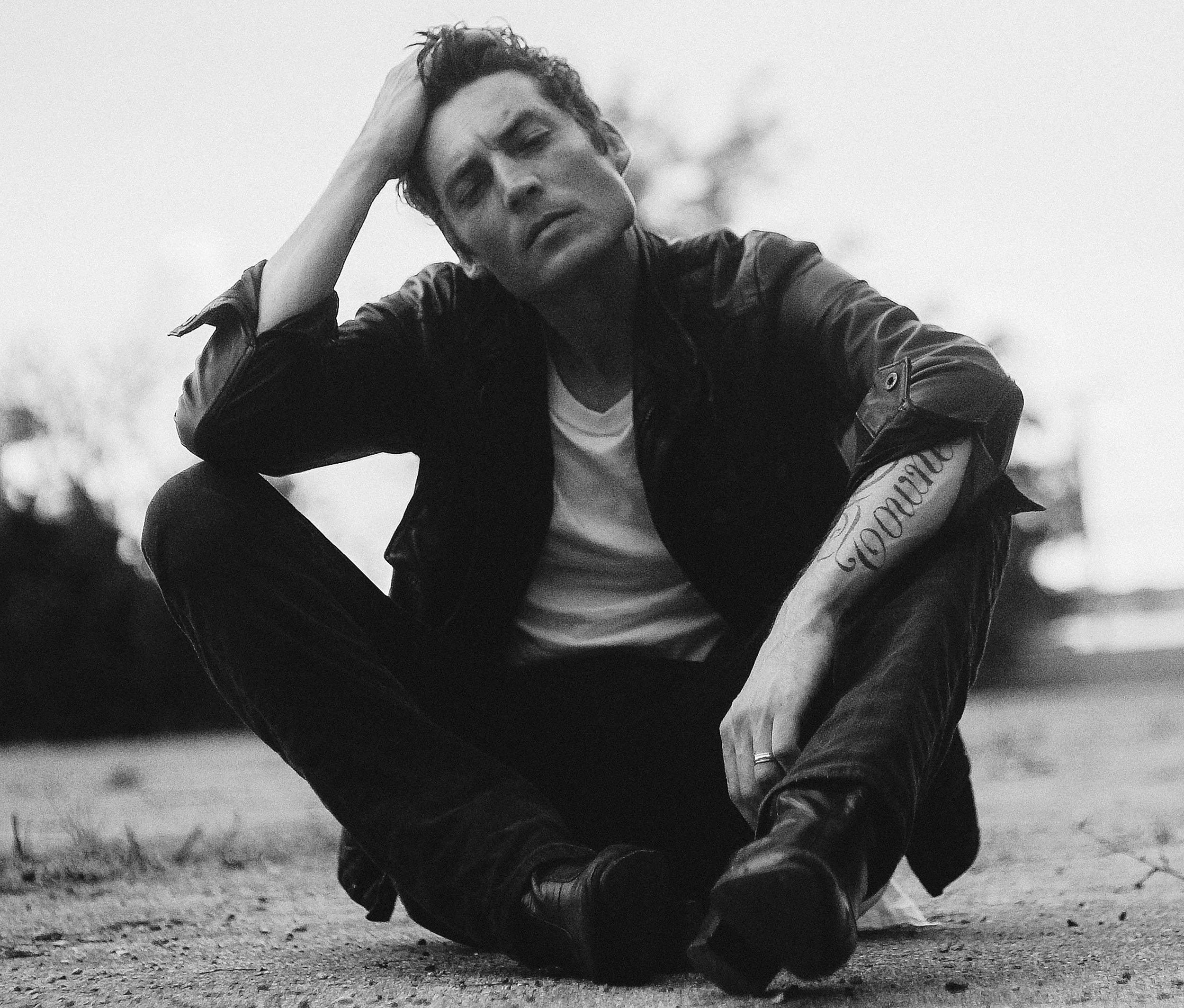

Photo credit: John Macy