The “bluegrass songbook,” a suitably vague though well-known concept in bluegrass and old-time circles today, is a phrase that references the collective of songs and tunes most popular and most played by the community that makes up bluegrass and old-time music. Most of the melodies included in this informal — though often gatekept and debated — canon have well established origins, from source recordings, legendary writers and composers, famous performances, and so on. Even so, it’s difficult to trace each and every Bluegrass Album Band hit or Del McCoury favorite back to the beginning, when it was first being adopted and popularized among jam circles, as fiddle tunes, by and for laypeople as much as the performing professionals.

With material by forebears like Flatt & Scruggs (“Foggy Mountain Breakdown” to “It Ain’t Me Babe”) or Bill Monroe (“Muleskinner Blues” to “Monroe’s Hornpipe”) or the Stanley Brothers (“Ridin’ that Midnight Train” to “Little Maggie”), the Osborne Brothers, Hazel & Alice, Reno & Smiley, and on down the line, it’s not so much a question of why or how their charming, archetypical songs made it to open mics and festival parking lot jams. But in modern times, as in bluegrass days of yore, just as many new, contemporary tunes, songs, lyrics, and melodies are being translated from professional studio recordings, radio singles, and on-stage hits to sing-alongs, play-alongs, and day-to-day jam fodder. And the process by which this happens is, part and parcel, what bluegrass and old-time are all about.

How did “Rebecca” become an almost meme-level instrumental in the past fifteen years? How did Frank Wakefield know that we needed a “New Camptown Races?” How many millennial and Gen Z pickers learned “Ode to a Butterfly” or “Jessamyn’s Reel” note for note? Each modern adoption into the bluegrass songbook, into that unflappable canon, is an idiosyncratic marvel unto itself — and perhaps no modern, original instrumental tune encapsulates this phenomenon better than John Reischman’s “Salt Spring.”

“Salt Spring” is truly the instrumental song of the post-Nickel Creek, post-Crooked Still, post-grass generation. As string band genre aesthetics dissolve in the global music marketplace, songs like “Salt Spring” typify this generation’s longing for music that feels honest, true, and real as much as it’s approachable, whimsical, and joyful; songs that celebrate the traditions that became the bedrock of these musics, without being predicated upon militaristic and arbitrary rules to “protect” or propagate those traditions.

A veteran of The Good Ol’ Persons, the Tony Rice Unit, and many other seminal acts of his own generation and time, Reischman knows firsthand the value of cross-generational knowledge sharing and his new album, New Time & Old Acoustic demonstrates this ethos in both conscious and subliminal ways. “Salt Spring” is a perfect distillation of these values and it’s truly fitting, as the tune will forever be enshrined and ensconced in the indelible, if not somewhat squirrelly and subjective, bluegrass and old-time songbook and canon.

(Editor’s note: New Time & Old Acoustic is available for pre-order now.)

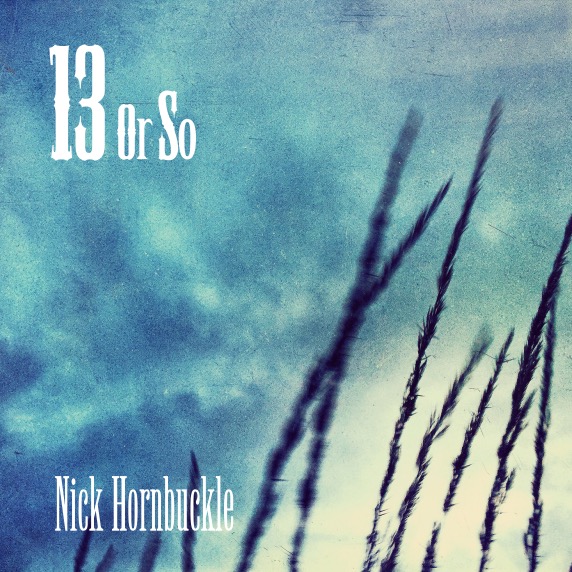

Photo courtesy of the artist.