Lex Price started early. As an eight-year-old growing up in Maryland, he became obsessed with the mandolin after seeing his cousin’s bluegrass band. When his father bought him one, he taught himself to play by listening to Sam Bush and David Grisman. Later, he graduated to guitar and bass.

But it was his Tascam four-track that held special interest for him. He turned his bedroom into a makeshift studio and turned himself into a one-man band. “I think I was 10 or 11,” he recalls. “I had a Tascam four-track that I recorded with constantly, just overdubbing myself over myself. That was my favorite thing. I didn’t put the pieces together that I could make a career out of it.”

And yet, that’s just what Price has done, albeit gradually. After recording his first album at 12 years old and gigging with alt-country bands in the ‘90s, he moved to Nashville and started playing bass for k.d. lang. During that time, he gradually migrated to a spot behind the board, never with any set plan, but with an adaptability that has become his calling card.

Through his work with Mindy Smith, Robby Hecht, Peter Bradley Adams, and others, Price displays considerable range and a sensitive ear for nuanced roots arrangements that complement but never overpower the vocals. On his records, the music usually works like a soundtrack to score the stories told in and the emotions conjured by the lyrics.

How did you move into production?

The first time I even considered it was when I was working with an artist name Clare Burson. This was 2003, I think, and we had been playing together for a couple of years. She was talking about making her first record, and it just seemed like a natural thing that I would play on it. Then she asked if I wanted to help produce it. Up until that point, that hadn’t been something I was pursuing, but I helped to produce that record and it sparked something in me. I loved it. That was the beginning.

So this wasn’t something you set out to do. It wasn’t necessarily a life-long ambition.

No, not at all. I wanted to play on records. That’s what I wanted to do since I was a kid. I always thought that was the end goal. I hadn’t even considered producing until we made Clare’s record, which I think we did in three days. I had moved to Nashville in 1998 or 1999 and, the first few years, I was trying to figure out what my place was here. I worked some odd jobs and started playing with people. I gravitated toward singer/songwriters — being a sideman for them. Clare’s album was about four years after I had been here, and that was really my first studio experience in Nashville. It really hit me hard, and I fell in love with the process.

That was your first studio gig? That’s really a trial by fire.

It was. But it wasn’t that scary, because we had been working together and we were friends. We just went in the studio, spent the three days, and that was that. There wasn’t time to overthink it. We had a great band and that was all we needed. And that’s still my favorite approach — to have a roomful of people and everyone feeding off each other. I enjoy that a lot more than building tracks, at least at this point in my life.

How do you prepare for a session? What kinds of conversations are you having with artists before you go in the studio?

The first conversation is always about the songs. I like for them to send me as many songs as they have, even stuff they might have forgotten about. Everything. At that point, I listen to all of them and start to choose songs and talk to them about that. You can get to know someone discussing their songs over a period of time. That’s the doorway into the next part of it, which would be figuring out what kind of vibe they’re going for.

Then we talk studios — what type of surroundings would be comfortable for them. Everybody’s different. For some folks, making a record means going to a very expensive studio. Well, maybe “expensive” isn’t the word. A very professional studio. But some people find that intimidating and they’d rather do it in a small studio, maybe a home studio. It’s all about the different situations you can get yourself into. And budget always plays a big role. Ultimately, it’s just getting to know someone and trying to figure out what’s going to make them comfortable, what’s going to make them feel like performing and having fun. I guess making them comfortable is a big part of my job.

Tell me about your studio. Where are you most comfortable?

I have my own studio that I mix out of, where I do overdubs. Then, for tracking, Nashville is a great place for studios. Specifically, I like Sound Emporium and Southern Ground. I’ve worked at those two quite a bit. The rooms just sound really good. The folks that run them and work there are fantastic. And great gear, for sure. Everything is dialed in really well. I have some friends with great tracking rooms, as well. It’s all budget dependent, wherever we end up. My process usually involves tracking at a studio that’s not mine. I get as much done as I can in that room, then bring it back to my place where I can finish it out with vocals or any overdubs that need to happen. Then I mix it and that’s it.

It sounds like those experiences as a musician inform your production work, but does it go in the opposite direction? How has your work as a producer informed your work as a sideman?

My hope is that I can see the big picture better while I’m playing and not just worry about myself. Mixing, too, informs how I play. If I’m hired as a session player, it definitely helps knowing what the engineer and the producer are going to have to deal with at the end of the project.

One distinctive aspect of your production is the emphasis on the vocals. Everything revolves around the singer’s voice, complementing it but never intruding on that space.

That’s incredibly important to me. I think I attract singer/songwriters who want that, as well. They want the lyric and the voice to be the center of it all, so I try to stay out of the way. The longer I do this, the more my goal is to be transparent as a producer and not put too much of my sound into it. I really want to get the song over. That’s what I’m thinking about going in and that’s what I’m thinking about through the whole process — somehow staying out of the way, but also helping to steer the whole project.

It’s like the Wizard of Oz: You have to stay behind the curtain but still pull all the strings — on a technical and aesthetic level, but it sounds like also on a social level.

A lot of it is social. That’s the trick. I don’t even know what to say about that. But it is true. You’re working with so many different personalities, and it’s so stressful for the artist. There’s always so much to worry about. My job is to do whatever I can to take your mind off those worries.

You’ve worked with artists on multiple albums — four albums for Peter Bradley Adams, two or three by the Westies. Is it easier to reach that point of comfort after you’ve gone through the process together, or does it reset itself every time?

I think it does make it easier. Peter and I have worked together for years now. We’re just wrapping up a new one, in fact. So we know each other very well. I think that helps. It’s a good question. I did a few with Robby Hecht. I think I’ve done three with him. It’s always nice to have people come back to do more records, and knowing their personalities certainly does help. It’s not like it’s any easier making the record, but there are certain aspects that you can foresee.

The first record you make with somebody, there are a lot of unknowns and that’s really exciting. You’re getting to know each other, and there’s a lot of fun in that. I’ve been fortunate that the folks I’ve been working with are all such cool people, and they have a good vision of what they want. We just all collaborate really well together. And we’ve ended up being friends, too, which is one of the best parts of doing this.

How did you meet?

With Peter, the way we met is, we ended up playing shows together. We played some shows with Clare Burson years ago as a trio, and we got to know each other and started making records together. With Mindy, a friend of mine brought her over to my house. My friend was like, "Hey, you have to hear her sing." This was before she had put out her first record. Our friend was trying to introduce us as music people, and we sat there and jammed for an hour or two. It was incredible. She played all of her songs that would end up on her first record. I was just blown away. We became friends and started playing together, then she made her first record and invited me to play on it. We worked together for years after that. When it was time to make a second record, she asked me to co-produce it with her. So it all stemmed from playing shows and working on tours.

We were talking about the emphasis on the voice, but it also sounds like you work with a lot of storytellers. Does that inform your approach? I’m thinking in particular of something like Mindy’s Long Island Shores, which has a very cinematic sound.

I don’t know exactly what my approach will be, but I am thinking about it. When I listen back to a song, I’m listening to the lyrics and the voice and I’m trying not to get caught up in all the little details. I’m just trying to listen to the song. If the song has made it through, then I know we’re on to something. I feel like that’s something I’m getting better at as the years go by — not getting caught up in the details. If the song is good and the performance is good, then you’re golden.

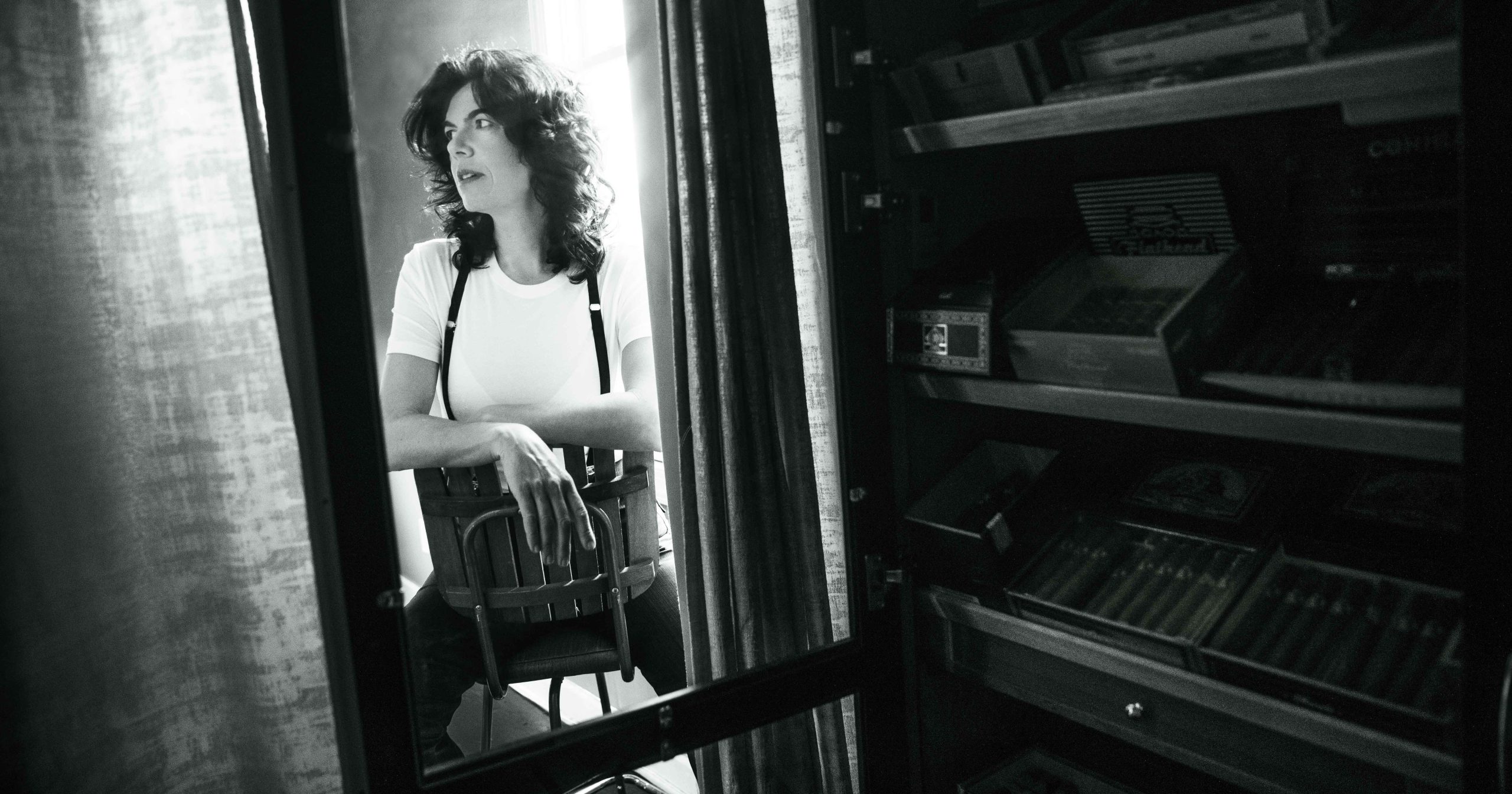

Photo credit: CJ Hicks