Chris Hillman — he of the Byrds and Flying Burrito Brothers fame — has returned with a new solo project, Bidin’ My Time, after more than a decade away. As he’s said in countless other interviews, he was resigned to living out the concluding chapter of his musical career. He’d all but packed up any ideas about recording another album, but he knew enough not to turn down an opportunity to work with Tom Petty, when it unexpectedly came calling. Petty produced Bidin’ My Time before his untimely death in October. The LP was originally supposed to be acoustic, but once the pair got in the studio, Petty’s ear for rock ‘n’ roll opened up Hillman’s songs. All 12 tracks, an array of original and covers, retain their originally imagined acoustic structure by sitting heavily in the folk and bluegrass traditions, but they’re expansive, grander realizations.

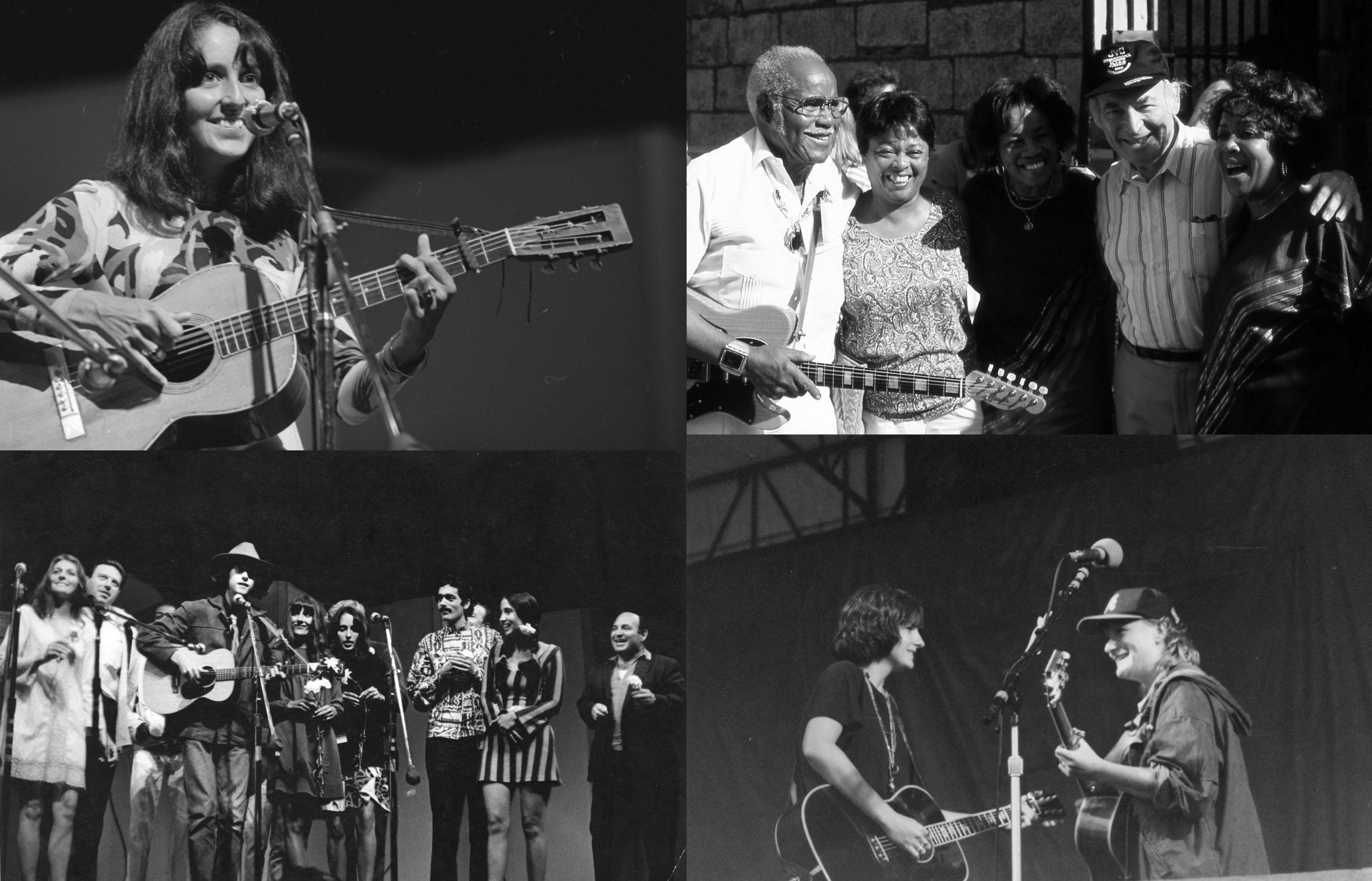

As the title suggests, the album finds the legendary folk artist concerned with time — lifetimes, past times, and “the times.” (Though the project was released before Petty’s death, that, too, has imbued the album with added meaning, but it’s not a point Hillman wants to exploit. He holds tight to the memories he made recording with the equally iconic musician, and only sometimes loosens his grip enough to let a rose-colored anecdote slip through.) On Bidin’ My Time, Hillman collected his career in songs new and old. He covered Pete Seeger’s “Bells of Rhymney” with former Byrds bandmate David Crosby and executive producer Herb Pedersen singing harmony. He also re-recorded Byrds co-founder Gene Clark’s “She Don’t Care About Time”; the song he co-wrote with Roger McGuinn, “Here She Comes Again”; and, of course, a tip of the hat to Petty with “Wildflowers.” Then there’s the title track and “Restless,” both of which reveal a presence of mind that knows more endings loom on the horizon than beginnings. If Bidin’ My Time ends up being Hillman’s last solo album, it only means he’s come full circle. Turn, turn, turn.

Tom Petty has covered the Byrds and you’ve covered Petty. What was it like getting in the studio together after you’ve both danced around each other’s music in the past?

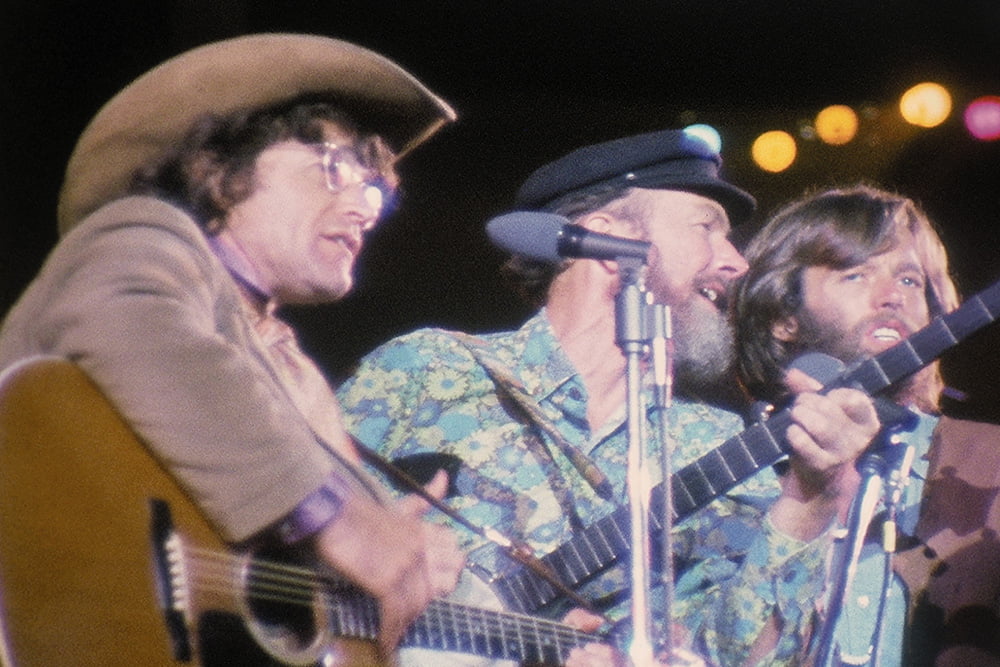

He had subtle ideas and he guided me in a way. Originally, when we were talking, before we started the record, I said, “You haven’t heard my songs.” He said, “Oh, I’m not worried. Believe me. If I hear something that doesn’t quite fit, I’ll let you know. We’ll work it out.” Which he did. It was a joy. Everybody had a good time, and nothing was planned, in that sense. It really started as an acoustic album, but then we had the Heartbreakers come in and overdub some stuff. It worked out great.

Your styles are different, but you obviously found a way to blend them. What did that process of compromise come to look like?

Well, I don’t know if I would ever stop to analyze it. Tom started out with a great love of the Byrds; he said the Byrds were so influential. But he took it 10 steps up the ladder, musically. There’s one song, “Listen to Her Heart,” that sounds so much like a Byrds song, but it’s highly evolved Byrds, and then he just took it off. As we all do, you start out — even as an actor or a painter or as a musician, of course — you start out really imitating, and then you seek to innovate. You take the best parts of what you’re learning as a young person and then you develop your own style — your signature style — which he did, and which I did to some degree. There’s a close proximity of musical styles all coming out. For me, for the Byrds, we all came out of folk music until we plugged in. And, of course, I came out of bluegrass. I must admit, I was a little nervous. I didn’t know if Tom would like my songs. As you know, I had no intention of making another record. I was done.

I know, and that’s what makes the timing so interesting to me. And, on top of that, there’s a theme of time throughout all the songs.

Well, I’m sitting there thinking, “I’m done.” Not out of bitterness. I said, “I’ve had a great time. I really don’t want to make any more records.” And this came along, and how can you say no? Toward the end, I started to say, “This is almost a conceptual record.” It’s touching on early acoustic, semi-bluegrass things that I started out with and then, through the Byrds, covering one Gene Clark song and redoing “Old John Robertson.” It sort of touched on different decades of what I did.

Right, even though Petty fleshed out the sound, it definitely holds to an acoustic structure between the folk and bluegrass elements.

That’s where I came from. The Byrds were very acoustic-oriented.

Speaking to that folk element, I’ve always associated the genre with containing really important messages. The song you covered, “When I Get a Little Money” — written by your friend — has such a beautiful message that it seems plucked from the ‘60s folk movement.

Well, I get handed songs a lot. Usually, you don’t take them. But this is the first time in probably 50 years where I get this CD — and, really, it’s a favor to my wife’s cousin who knew this young man and he’s a school teacher — and I hear this song, and I think “Well, that’s fantastic.” It had so many different little nuances to it, and I asked him if I could record it. He flipped out; he was so happy. It came out great.

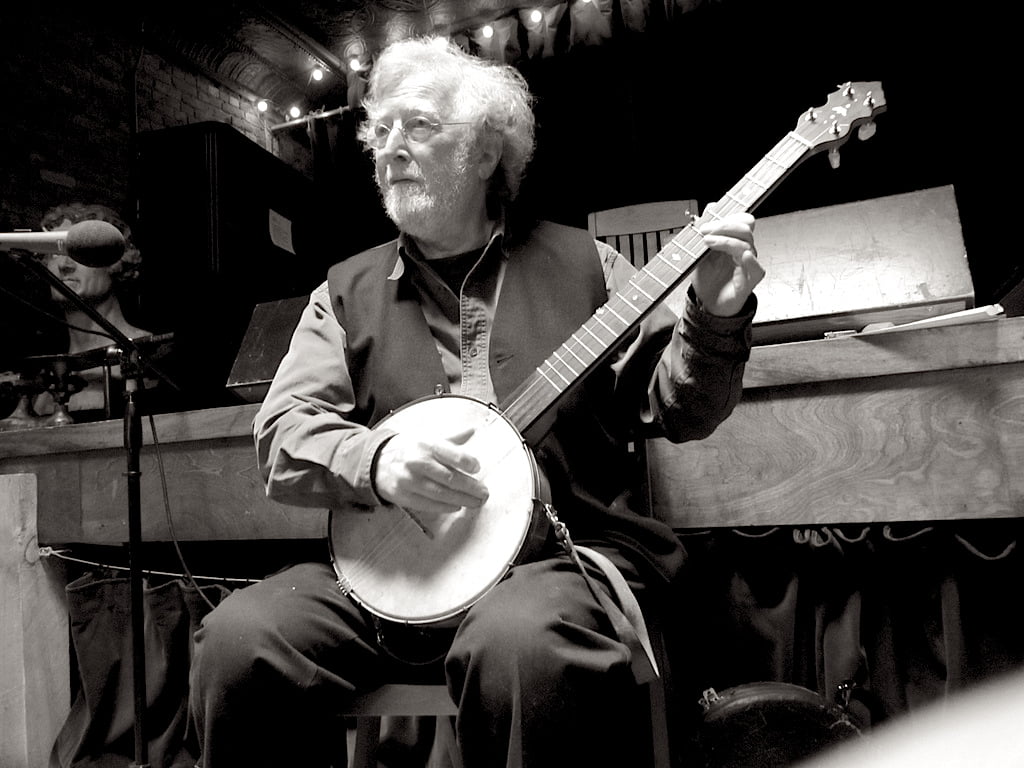

And you’re right about the folk music and the message. Our first manager in the Byrds really drilled it into our heads. He said, “You guys go for substance or depth in your lyric, whether you’re writing the song or whether you’re finding the song, because you want to make a record you’ll be proud of 40 or 50 years down the road.” “Turn! Turn! Turn!,” well, Roger had remembered Pete Seeger doing that, and how Pete had put the melody to Ecclesiastes. That was a real nice tune to cut, as was “Bells of Rhymney,” another song where Pete put melody to a Welsh poem. You could dance to these songs, but they were in the folk tradition. There was a deeper message to each song; they were story songs. “Turn! Turn! Turn!” is almost an owner’s manual on how to live.

Right? That is, if you’re paying attention.

Yeah, but as Solomon wrote it, it’s all in black and white. There’s no gray area there, which is fine. I think we all, having come out of folk music, had that sense of story or some depth to the lyric. We tried to. We didn’t always — we cut some stupid songs. At the time, you think it’s the hippest thing in the world, and you listen back and think, “Why did I record that?”

So your former manager’s advice stands true, then.

Well, I’ve lived by that rule. Like I said, what I think is really brilliant at the time doesn’t always stand up over the years.

How do you see folk music impacting listeners today as opposed to what you were trying to convey back in the ‘60s and ‘70s?

I don’t see it any different. As you get older — and here I’m very happily married for 38 years, and I’ve got two grown children, I’ve got a granddaughter; the greatest blessing in my life — if I sit down and write a song, it’s going to be something closer to a mini short story. There’s a song on the album, “Such Is the World That We Live In,” and it was a tiny jab, in a political sense, but it was also how I felt about how things had so rapidly changed. I wasn’t trying to tell anybody how to live. It’s the grandfather telling the young people things are acceptable now that never were acceptable, in the sense of relationships and this and that.

I grew up, as did everybody my age, with a sense of civility and manners. We were taught manners, we were taught responsibility, we were taught, if we got in trouble at school, we’d get in trouble at home. It was never a case of the parent suing the school because the school teacher yelled. There was a sense of order and structure. It’s not as I see it anymore. Am I going to be able to do anything about that? No. What keeps civilization on an even keel is laws: moral laws, ethical laws. And we seem to have strayed away from that all over the world. I don’t think it’s a matter of evolving. So you’re accepting it in the song.

But it wasn’t always an ideal time. Out of folk music — this high, moral tradition — came Altamont, rampant drug use, and this degeneration into chaos.

You’re absolutely right. Okay, I played Monterey Pop, a beautiful festival. It was the true peace and love thing. And then, within a matter of two or three years, there was Altamont, which I played, too, which was the darkest, most frightening day I’ve ever spent in music. The minute I got off of that stage, I took off. It was dreadful. Then it started to slide into this chaos. The ‘70s were one of the darkest decades.

Right, so then, if you look at history’s cyclical nature, we’re seeing a similar pattern as what took place nearly half a century ago.

Then you have to look back thousands of years. There’s some validity to the story of Genesis — that man is determined to destroy each other in some way, shape, or form. I don’t hold the ‘60s up as some wonderful time. A few years were great. I think my generation were trampling on all those things I told you about that kept our civilization pretty much in order — the values and things. But we’re not going to talk about that. We’ll talk about music. Music never dies.

When it was confirmed to me on that Monday that Tom passed away, I was so much in shock that I said to the guys, “We’re going to cancel the next four shows and go home.” Roger McGuinn called me — I hadn’t spoken to him in a year or two — he called me up to talk about Tom. I said, “I’m going to cancel and go home.” He said, “No, you’re not. Tom wouldn’t want you to cancel your shows.” Tom and Roger were very close friends for years and years. Roger laid it out to me in a gentle way. I said, “You’re absolutely right.” We continued on and finished the shows in Tom’s honor.

So then how did the album’s significance change in light of his passing?

Here’s the fine line: I am not using this as an opportunity. I’d rather have that album in the trashcan and him alive. It’s a very touchy subject for me. Here was a man who was an incredibly big rock star, but he had more of a grip on humility than any of us can aspire to, and I’m a Christian. We aspire to have that virtue of humility. He had it. Every morning, he would come into the studio with a tray of coffee. He didn’t have one of his employees bring it. One time, I drove up and I was getting stuff out of the car, and he said, “Let me take that for you.”

I can see why you’d want to be protective of that.

Tom’s death shocked everybody in the world. The thing he possessed besides humility, he was so accessible as an artist. His music affected everybody in a positive way — 40 years, an incredible catalog of work. Everyone could relate to Tom Petty. He was everyman. The absolute best rock guy we had, post-Beatles. I didn’t see any health issues with him. He had something with his knee or his hip that is common territory, when you get into your late 60s.

It was so unexpected. In that spirit, then, what you were able to accomplish on this record …

I wanted to do a great album. The opportunity coming along when I wasn’t going to record anymore … One of the last conversations I had with Tom — the album was about wrapping up — I said, “Tom, I can’t thank you enough. This exceeded my expectations.” He said, “It exceeded my expectations.” I said, “It’s a wonderful way to end my career.” He said, “What are you talking about? I’m not done with you. I’ve got other plans for you. We’re going to get to do some more stuff.” I thought, “Wow.” That was nice to hear. If anybody could’ve put the Byrds back together — Roger, David, and me — it would’ve been Tom. He knew us all so well. It didn’t happen, but that’s okay. We all loved him. If you didn’t know Petty, you loved him.