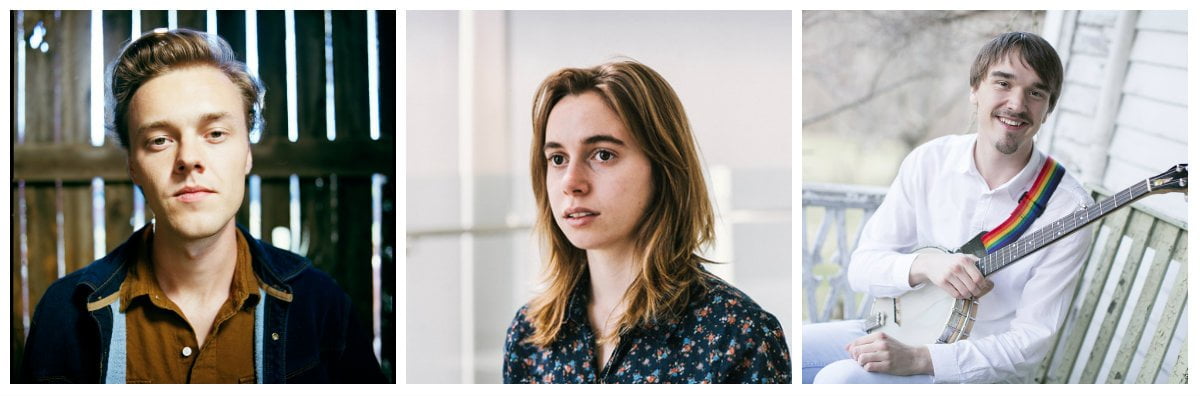

Sam Gleaves and Tyler Hughes are very proud to have grown up in southwestern Virginia, a swathe of Appalachia that birthed the Carter Family, the Stanley Brothers, Jim & Jesse McReynolds, and so many more icons of roots music. Released in June, their self-titled duo album is a collection of old-time, traditional country, and mountain music that, on the surface, feels like an album exhumed from a time capsule of southwest Virginian music from bygone eras. But, when you begin to unpack Sam and Tyler’s perspective — yes, they’re native Virginians steeped in their homeland’s musical heritage, but they’re also young and openly gay — you begin to fully appreciate the subtlety, the thoughtful care, and the love that they’ve put into curating and recording this set of tunes.

Speaking to Sam and Tyler was a welcome reminder that, in a time when phrases like, “middle America,” “silent majority,” and “forgotten middle class,” have become daily buzzwords and when the divisions between urban and rural, rich and poor, right and left are seemingly at their greatest, it’s more important than ever that we have these difficult conversations, that we listen to each other, and that we love one another.

So much of what you guys are doing on the record is simply putting a spotlight on perceptions of and presuppositions about people who come from central Appalachia in general. On “Stockyard Hill,” an original song and the first track on the album, you sing, “I’m proud of the way that I came up …” How did your families inspire this song through watching you grow up in the music and grow up to be who you are, living truly and openly?

Sam Gleaves: I wrote this song based on the words and experiences of my great aunt, Corrine Thompson — my grandmother’s sister. She’s an amazing woman, a real matriarch, a really loving, good presence in my life. I feel like she’s a great example of a really open-minded, intelligent, progressive person from southwest Virginia. She’s a great example of someone who defies a lot of stereotypes about people from central Appalachia. I’ve only ever known her to be loving and accepting of all people. She would think that a lot of the political discourse — this really hateful, divided situation that we have now — is so contrary to who she is as a person, the culture that she comes from, and the culture that I come from.

Tyler Hughes: As far as family influence, I grew up in an average, working/middle-class family. They are real people. I think that’s what influences my music and specifically the music that we put together on this album the most. I come from a strong union family: My grandpa was a union coal miner for over 30 years. My family is much like Sam’s in being very accepting and loving. There’s not really a judgmental side to them. They have a great appreciation for the place we come from, but they also have a wider view of the world beyond just what happens in southwest Virginia. I think that’s what influences me most and what makes me most proud to say that I am from southwest Virginia. Probably the number one thing I want to tell people when I meet them is that I’m from southwest Virginia, because people do have such misconceptions, but there are people out there that don’t fit into these exaggerated beliefs and misconceptions.

SG: I came out when I was in high school and I had a really close community of friends around me between my classmates in school, people that I played music with in the old-time music community, and also my family. When I came out to my family, they all knew other gay people. It wasn’t an unfamiliar or unexpected thing, when I came out. [Laughs] I think my parents gave me permission to be who I am. Not only as a gay man, but as an artist and a human being. A lot of people don’t get that permission from their parents. They never discouraged me from singing professionally, and they never told me my writing wasn’t important, but just the opposite. They wanted me to write and they wanted me to travel, to sing, to get to know musicians.

I definitely have had to think a lot about how I talk about these issues because, when I recorded my first album, Ain’t We Brothers, everyone that interviewed me asked me what it was like to be a gay man living in Kentucky and growing up in southwest Virginia. In rural places all across America, LGBTQ people need a lot of support. There are a lot of needs that aren’t met, in terms of communities not being able to come together and celebrate our identities, and also work for equal rights. There’s a lot of work to be done, but I’ve been very fortunate to have a good, welcoming experience being openly gay, in the old-time community, but also just living in Virginia and Kentucky.

Following on that then … I wonder if either of you considered that this project could potentially be that very permission for a listener? There are a lot of LGBTQ individuals in these spheres — Appalachia, the South, roots music — that aren’t out. Did you think this could be validation for other LGBTQ artists to be out and to lay claim to this music in a more assured way?

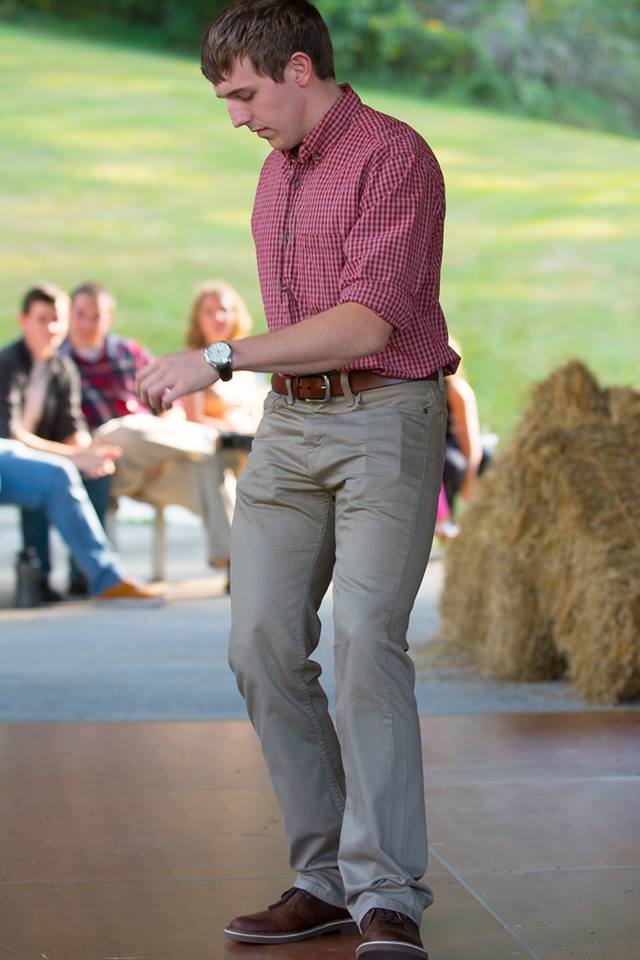

TH: I think about that quite often, even just for regular performance, even though we don’t stand on stage and advertise that we are gay musicians — that’s not exactly the shtick of our show. It’s nothing that we try to hide, but it’s not the main focus. I try to keep in mind that, to someone who might be struggling with their identity, it could be a very powerful moment for them to see someone they can relate to doing something that maybe society or someone around them is telling them they can’t do, or that something is only reserved for certain people. Any time that I’m playing music, whether it be working on this record or just being on stage, I think about that. Because I had a similar experience. When I first met other gay musicians, it really empowered me to think about how I could also live an open and full kind of life and still do the thing that I love the most.

As diversity becomes more of a hot-button topic in roots music communities, a lot of bystanders seem to assume that, because more LGBTQ individuals are becoming visible in bluegrass and old-time, we’re coming from the outside in or that we’re “infiltrators” and appropriators of the music. But here you both are, born and bred in this area of Virginia and Appalachia that’s such a hotbed for this music. How do you approach people with this perspective?

SG: I think it’s important that you mentioned that. We love the place that we’re from, but I think we have to acknowledge that there’s a lot of work to be done. I don’t know how else to say it. I see this especially in the bluegrass community, which we’re sort of on the fringes of. We also play old-time country music, which is just a blend of all of these things, so we end up in these environments where genre doesn’t keep us from playing in a wide, wide range of places. We want to represent our communities and the Appalachian region well, but we also have to acknowledge that there are people in these genres of music that do feel that it’s not right for gay people to be out in their performances — like just singing a love song about a same-sex relationship. I’ve never had any negative backlash from anyone at a concert or from any producer or from any person on stage that I’ve ever worked with. I’ve never had anyone say openly, “You shouldn’t sing that song, or you shouldn’t tell that about yourself.” I’ve only ever had like one or two people ever walk out of one of my shows that I knew was because of what I was singing.

I’ve had a lot of conversations about these topics in the past several years and that’s certainly not always the case. Why do you think that is?

TH: I don’t know … luck? [Laughs] No, every audience is different and every situation is different, but the number one thing that I think about, when I first walk out on stage or when I first get to a venue or when I go out to meet an audience after a show, is that, first and foremost, I’m a musician and I’m a performer. I think more about that than anything else. If somebody didn’t want to listen to my music anymore because they suddenly found out that I was gay, it wouldn’t hurt me any more or any less than if they found out that I didn’t like bananas so they didn’t want to listen to my music anymore. To me, it’s their qualm and, even if I feel that it’s a silly thing to let get in the way, they may not. I try to understand that — I would have to disagree with them — but I would at least try to understand their position. I think about the fact that I’m presenting myself more on the level of musician and a performer first. And also just being a person. Being gay is only a tiny sliver of my identity, when it comes to all of the things that make up who I am.

SG: You know, in country music, there’s a tradition and an expectation that performers be friendly, that they engage with audiences. I think that is a big reason why people don’t come up to us and say, in person, “I was upset that you all mentioned the women’s movement before you sang ‘Bread and Roses,” or “I was upset that you wished everyone a happy Pride month.” I think it’s because we really do try to be friendly and welcoming to people. Not that other people who experience discrimination and hatefulness are not being friendly — I’m not saying that. To some degree, what you put out can be what you receive back. We do try to be a part of that tradition of being good to people.

That makes me think of “When We Love” from the record. Tyler, what was it like to write this song and to sing this song while you are faced with this loud, mainstream, idea that a lot of people out there don’t love who you are as a person? How do you espouse this kind of love, when it’s not what everyone else is also putting out into the universe?

TH: I really don’t find it that difficult. That’s not to say that I’m not angry with the situation we find ourselves in or that I don’t get frustrated when there are setbacks. I don’t really know where I align myself religiously on most days, but I do think that, no matter who you’re worshipping or what kind of life mantra you’re following, we are all human and we’re all sharing in the human experience. Part of that, to me, is just loving one another. I still live in a small coal mining town, and I would say that at least a good 70 percent of my friends probably voted for the president. They may not agree with everything he says, but they feel that they are supporters of his. I know them as people and I know they’re not judging me — even if deep down in their hearts they may not really agree with LGBT rights or equality for all people. That’s not a big enough issue for me to let friendships or relationships go. Some of my best friends in the world align themselves with conservative values and conservative movements. It just doesn’t bother me, because I’d want them to look at me in the same way. At the end of the day, we still all need each other. These are differences I can put aside for most people, as long as they put them aside for me.

Photo credit: Susi Lawson