While playing music in a bar, Tammy Rogers of The SteelDrivers learned a lesson that would guide her life choices. After Rogers graduated from college, she was happily earning her living as a musician. But she wondered if it was enough.

“I felt like it was all about me, rather than what I could give back and put into the world.” She had considered teaching or studying music therapy, thinking that, “Maybe I needed to be actively doing something to help.”

Here’s where the bar band comes in.

“I remember this like it was yesterday. I sang a gospel song.” Rogers said. “And after the set, a couple came up to me and said, ‘Thank you so much for singing that song. It meant so much to us.’ And it was like a light bulb came on – answering the question, ‘What should I be doing with my life?’”

For Rogers, the interaction with that couple in the bar was God giving her the message that she was doing what she was meant to do.

“The music that you write, the music that you play can touch people and help them, whether it’s in happiness or sorrow.”

Bluegrass musicians often incorporate old and new gospel songs into their performances. Whether it’s the melodies, the spine-tingling harmonies, the familiarity, or the content, gospel music has an enduring appeal to the full spectrum of bluegrass fans, regardless of culture or religion.

Last year, The SteelDrivers, as well as the young band High Fidelity, produced gospel albums – Tougher Than Nails and Music In My Soul, respectively – and Chris Jones released a gospel track, “Step Out in the Sunshine.” For them, the music is personal. They all come from a place of faith and sincere connection to the good news of the gospel, as well as loving the music itself.

In the rural communities where bluegrass began, life often centered around church, as a place of prayer, music, and friendship. Eventually, Southern gospel music also took on a life independent of worship.

Wayne Erbsen wrote in his charming book, Rural Roots of Bluegrass, “By the 1850s, songwriters were composing new gospel songs to appeal to the thousands who flocked to the rapidly growing number of shape-note singing conventions throughout the south.”

These lucrative gatherings – possibly more entertainment than spiritual – continued well into the 20th century. Erbsen told BGS that people would bring the books they already owned, but when they arrived, “they had to buy more books” to learn the new songs. The publishers hired excellent performers to attend the conventions and inspire the singers.

Erbsen wrote, “The songs and styles that were part of this shape-note singing convention tradition eventually merged with bluegrass instrumental and vocal styles to create a new genre now known as bluegrass gospel.”

Bill Monroe, like others of his generation, was exposed to religious-themed music. While performing with brother Charlie, Monroe’s first hit record was “What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul?” And just as he learned the blues from Black fiddler Arnold Shultz, he was “fascinated by the music of the Black churches,” Chris Jones said. That’s where Monroe learned “Walking in Jerusalem,” popular today for its rich harmonies.

High Fidelity – Jeremy Stephens, Corrina Rose Logston Stephens, Kurt Stephenson, Daniel Amick, and Vickie Vaughn – is steeped in traditional bluegrass. Corrina’s parents got hooked on Reno & Smiley and the Stanley Brothers looking through department store record bins – and Corrina has stayed close to the traditional fold ever since. “It feels like it’s in my blood,” she said.

Jeremy learned to sing harmony from his grandfather. After he picked up the fiddle, a school bus driver made him a cassette tape of classic bluegrass. “And that tape was transformative to me,” he shared.

All of High Fidelity’s music is infused with the harmonies, instrumentation, and themes of early bluegrass performers. The friends who make up High Fidelity (the name comes from the words often on labels of early bluegrass records) came together as a band to compete in the SPBGMA band contest. They never imagined they would take first place. So, “It was this overwhelming gift that we won,” Corinna said. “It almost felt like divine intervention.”

“And everyone in High Fidelity is spiritual,” she continues. “We’re all Christian folks. We all identify with the songs that we’re singing.” So, from the earliest days, she said, they felt a gospel album was in their future, to “honor the Lord and thank him for giving us this gift.”

During a long period of illness that Corinna later learned was caused by toxic mold in their home (they since have moved out, and she feels a lot better), she received another gift from God, she said. She woke in the early hours of the morning with a song in her head that was so compelling, she had to get out of bed to record it. “And almost all of the verses just came out, bypassing my conscious brain.”

That song is “The Mighty Name of Jesus.” It is a centerpiece of, and the only original on, their recording, Music In My Soul. Corinna said, “We wanted [the project] to feel like a quintessential High Fidelity record, very bluegrassy.”

She wanted to emulate another early hero, Carl Story. When listening to Story, she said, “It wouldn’t even register that I was listening to a gospel record. It was just such good bluegrass… I wanted Carl Story’s vibes.”

Their recording successfully and joyously channels the spirit and musicality of the earliest bluegrass stars. High Fidelity worked hard to find little-known gospel songs from a variety of sources, performing them with the same enthusiastic vigor that they bring to their secular music. Listeners will recognize classic banjo introductions and harmony variations that have been passed through generations since bluegrass hit the radio.

And just as Music in the Soul is undoubtedly High Fidelity, nobody but The SteelDrivers could have created Tougher Than Nails. It is gritty, bluesy and achingly human.

Rogers said that for years, The SteelDrivers’ most requested song has been “Where Rainbows Never Die,” from the 2010 recording Reckless.

“We’ve gotten so many emails, messages, people come up to us at shows, telling us how they’ve played the song at their dad’s funeral or for grandpa or whomever and how much it’s meant to them.

“It doesn’t say the word God. It doesn’t say the word Jesus. It doesn’t even use the term heaven. But it is a gospel song, a spiritual song. It’s about passing on to the next life. To me, it is such a powerful, beautiful way of sharing,” Rogers said.

In the same way, she said, a SteelDrivers’ gospel collection wouldn’t be “preaching at people or using even the language they’re familiar with. But if the message is the same, why not?”

On Tougher Than Nails, expect the same gutsy, no-holds-barred, gorgeous vocals that we love from The SteelDrivers. Their original gospel songs are as much about the dangers, choices, and blessings of humanity as their songs about liquor, guns, guitars, and heartache.

They ask us to think about Mary Magdalene, and how she balanced love for the man with love for the divine. They wonder if Judas’ heart broke as he fulfilled his destiny of betrayal. And they celebrate the victory of love over the cruelty of crucifixion.

Even “Amazing Grace” is uniquely SteelDrivers – starting with a primitive drone that weaves into the blues-driven rhythms we associate with Black Baptist church choirs.

Chris Jones is one of the most enduring and admired singers in modern bluegrass. He also is a SiriusXM radio host and writer, and a respected commentator on all things bluegrass.

Jones recently recorded “Step Out In the Sunshine.” Jones learned the song from listening to Ralph Stanley on Jones’ “all-time favorite gospel album.” It’s a song of hope and joy.

“I think the feeling and sincerity of gospel music touches all different kinds of people. It has a broad appeal, whether you’re a believer or not,” Jones said.

He noted that many bluegrass fans relate to melodies and arrangements and often overlook the lyrics. He referred to a listener who loved the song, “Julie Ann,” because it was so happy. (It’s up-tempo, but sung by a man begging his wife not to leave him.)

But lyrics do matter to the musicians who sing them.

Jones echoed a sentiment reflected in the gospel choices of High Fidelity and The SteelDrivers. A religious commitment “makes you a little more selective of what you’re willing to sing. Is this a message I really want to send to people?” Jones chooses gospel songs that are welcoming and inclusive.

High Fidelity’s Jeremy Stephens said they avoided lyrics that sounded like condemnation, the ones that say, “You’re bad because you do this and you’re bad because you do that.” He said Music In My Soul “is our hearts talking to your hearts… the Lord said, ‘Come to me as you are.’ There’s so much peace and love and acceptance in him.”

Award-winning singer and guitar player Greg Blake currently performs with his own band as well as with Special Consensus. Blake had a ministry for 30 years before becoming a full-time musician. He said he has learned a lot over the years about judgement, love, and being open-hearted. And his insights inform his choice of spiritually-oriented songs.

“When I was younger, and probably more zealous and less informed, I felt like I needed to be ‘right.’ But as I got older and looked at the teachings of Jesus, I saw that his message was more about right relationships,” rather than proper dogma or theology.

So today, Blake says, “I like to bring into gospel even songs that may not have a strong Christian element, but are just good, positive songs… that leave one with a sense of hope and love and care for one another. I think that’s the message that people of the world need to hear today.”

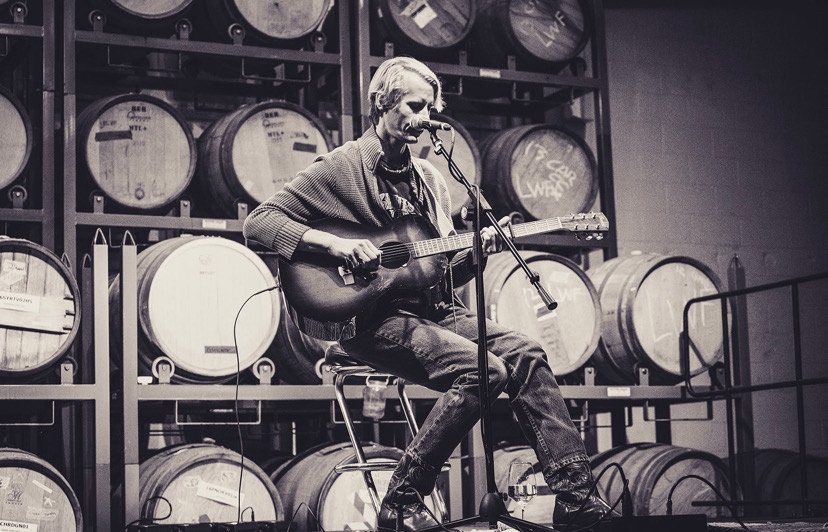

Photo Credit: Photo of the SteelDrivers courtesy of the artist; photo of High Fidelity by Amy Richmond.