When M.C. Taylor decided to make another Hiss Golden Messenger album, he instinctively knew it needed to be done in real time, in an actual studio, in his adopted hometown of Durham, North Carolina. Recorded in the summer of 2020, Quietly Blowing It reflects a joyful spirit even as a fog of anxiety hung over the sessions. And in some ways, Taylor believes that a sense of tension is what this album is all about.

But in contrast to the image of making a million minor mistakes, Quietly Blowing It may be his most accessible album yet. (His prior effort, 2019’s Terms of Surrender, landed a Grammy nomination for Best Americana Album.) As he’s done for years, Taylor asks a lot of questions in his lyrics without filling in the answer. One could say that he positions himself as a moderator who introduces a conversation, rather than an expert who knows everything about everything.

“That’s always been the way that I write,” he tells BGS. “I’ve been talking for many years about this idea of making an album that’s full of questions with no answers. In a lot of ways, I’m less interested in the answer than I am in the question, if that makes sense. Because the answer might change from day to day. I find the question often to be the thing remains steady, more or less.”

Not long before heading back to his native California to finally visit his family there, Taylor caught up with BGS by phone about Quietly Blowing It, releasing June 25.

BGS: One of the reasons I like listening to “Sanctuary” is because you can hear the band in the groove, in the space between the verses. It makes it feel like a band record.

Taylor: I think for the type of music that I make, the best light that it can be shown in is when you can hear everybody working together. The music is a collective music and it thrives on the collective energy of the players. That’s why I was hesitant to jump into making anything totally remotely. If my options were to either record remotely or do nothing, I would have chosen not to make a record because that collective energy feels really important to this music.

The second time I listened to this album all the way through, I really noticed the drums. It’s like its own energy coming through. Did you feel that too?

Yeah, in a lot of ways the record was written around the drum parts. I spent a lot of time coming up with the way I wanted the drums to work, at home, and sketching out drum patterns and drum parts, and layering different percussive elements over that. Then I brought those ideas to the two people that played all that stuff: Matt McCaughan played the drum kit and a friend of mine named Brevan Hampden played a lot of the percussion. It was meant to feel like this churning machine, almost. You know what I mean? A lot of the parts are pretty simple, but they’re sympathetic to the songs. Simple in theory, but very hard to play in a way that swings as hard as Matt and Brevan do.

To me, “Hardlytown” is about people who are staying the course against a world that’s pushing back against them. Is that pretty close to what that song is about?

Yeah, that song is addressing this idea of the way that we set up the systems in order to live our lives the way we think we want to. And how, so often, what we give feels like more than what we get back. There are many ways to do that math, of course. When I started out being a musician, I spent way more than I made back. That was like the first 15 years of my life as a musician, playing out in public.

However, there’s the whole existential math. [Laughs] Where you start to factor in joy and spiritual payoff, and that becomes another set of equations that start to figure into it all. I was trying to work my way through that, “Hardlytown” being the place where maybe you don’t get back what you put into it, but you keep at it anyway. It’s meant to be a little salty around the edges but it’s meant to be a song of hope. It may not be unqualified hope, but I think the heart of that song is a certain kind of hope.

There’s a line in that song that says, “People, get ready / There’s a big ship coming,” and that reminded me of your love of Curtis Mayfield. Why does his music resonate with you?

He’s the whole package to me. He has an absolute command of groove. His arrangements are so elegant and affecting. He really knew how to make you feel something, and his writing is second to none, in terms of finding that sweet spot between the sacred and the everyday. I’ve said this a lot lately, but he was really good about singing about the potential of hope. You think about the time during which songs like “People Get Ready” were written. It’s hard to imagine there was an abundance of hope for him and the communities that he moved through. But they somehow continued to write these songs that feel anthemic, in the way that they talk about the potential of hope, and how important hope is to carry, even if you can’t fly the flag at the particular hope at that moment.

In the video for “If It Comes in the Morning,” you have Mike Wiley, a Black actor, lip-syncing to your track. Why did that treatment appeal to you?

It’s been interesting to hear certain reactions to that video. First of all, Mike Wiley is a friend of mine that I’ve been doing work with, off and on, for over a decade. He’s an incredible stage actor. And I knew that I wanted somebody to be looking directly into a camera as they lip-synced the words. So, my thought was, who can stare into a camera for the duration of the song without flinching? And not have crazy camera eyes? I can’t do that, I don’t have that skill set. You put a camera on me for more than three minutes and I start to look like George Jones or something. [Laughs]

So, my intuition was to get in touch with Mike Wiley. He’s an expert at that. It certainly was not lost on me that Mike Wiley is a Black actor, so there was going to be added layers of information with that video. And heightened interpretations because of the moments we are living through collectively. I’ve heard some people say, “I don’t get this video. What is this video trying to say or do?” And plenty of people have not commented either way, whatever, they like the song. Other people have been angry about it. But when I see the video, I see my buddy Mike Wiley lip-syncing the words and Mike happens to be an extremely gifted actor who is Black.

What does the word “it” represent in that title, “If It Comes in the Morning”?

I mean, it depends. “It” could be victory, defeat. If things go my way in the morning, how am I going to behave to people that were on my side, or people who were on the other side? If defeat arrives in the morning, how am I going to behave to people that I was working with, or to people who were working against me? I was thinking about how I might behave to someone that might be my adversary in some situation. Would I behave with respect? Or would I kick sand in their face? I like to think the former, but sometimes I think the latter. And that’s a “quietly blowing it” moment. [Laughs]

How would you describe the room where you wrote these songs?

It’s about 10 feet by 12 or 14 feet. It’s pretty small and it’s full of guitars, books, records, and sometimes a drum kit and amplifiers. Depending on my mood, it can feel like an oasis or like a prison cell. [Laughs]

During that time when we were all staying home, I spent a lot of time on the greenway. Did you get a chance to get outside, too?

Yeah, we got outside a fair bit. We have a pretty big backyard. Durham is full of green spaces, so yeah, I found the outdoors to be a balm over this past year. No question about that. We did a lot of camping this year, and that was fun also.

How did you wind up in Durham?

Many years ago, I went to grad school at UNC. This was back in 2007 and my wife and I just ended up staying. I don’t even remember what our intention was, whether we thought we were going to stay for a long time or move somewhere else. But this was pre-kids and over time North Carolina just started to feel like home. We bounced around this region a lot. We lived in Chapel Hill first and we lived outside of a small town called Pittsboro. Then we gravitated towards Durham. It’s a perfect-sized down in my opinion. Lots of incredible food, art, music, so this is where we ended up and it feels like home.

Before this band took off, I’m sure you were doing a lot of odd jobs. I think I read at some point that you were selling swimsuits over the phone?

Yeah, I did. That was a long time ago, back in college in California. I didn’t last. I was selling women’s swimsuits over the phone. Like, I was a 22-year-old guy and didn’t know the first thing about anything about that. [Laughs] I had no business answering those telephones. They should not have had me there. They didn’t have me there for long. They fired me after two weeks. They could tell I was the wrong person for the job.

You’ve said elsewhere that you still feel the pull of California. Is that why the video for “Glory Strums” looks the way it does?

Yes, it is. In normal times I would be in California many times a year. California is where most of my family still lives. Like many people, I haven’t seen them since this all started and my kids haven’t seen my parents in almost two years. I’m really pining for California in a way that I haven’t before. Because I’ve traveled to California so frequently, I’ve kept that homesickness at bay. It never affected me because I knew that within the next month or two months I would be out there again. I haven’t been out there for a year and a half and I can really feel it.

It made me think about this article in the New Yorker in 1998 called L.A. Glows. It’s about a native Californian meditating on the light in Southern California. I remember reading it at the time and thinking it was interesting. I understood this theory that different places could have different qualities of light that would affect people that knew that place. But now I can feel that on an emotional level.

How did that video come together?

Vikesh Kapoor is the director and he is someone I have known for many years. Back in 2013 or 2014, I was playing in Portland, Oregon, opening up for Justin Townes Earle, and I was traveling alone. I was looking for someone to sell merch for me, so I put out a call on social media, I think. Vikesh volunteered to do it and we met that night at the merch table, where he sold my stuff. We kept in touch after that. He’s a songwriter himself and he’s made a few great records. And he’s a pretty respected photographer.

I knew that he was living in Los Angeles now and I got this wild hair that I thought Vikesh could make a video. We talked a lot about the light – the hazy, Southern California quality of light that I was missing. I asked him whether he thought he could get that into the video and he did, to his great credit. He didn’t have a whole lot to go on. [Laughs] He made something that is really beautiful and it does speak to the place where the video was made.

During that time when you were touring solo, what did you like most about just you and the road?

I still do that kind of touring once in a while, just to get that feeling again. I mean, there’s something about being footloose out on the road that can be really exhilarating, even still. I’m one of those people that picked up Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and Desolation Angels when I was 17 years old and read them. I was just like, yep, this is the life for me. And the older I get, it’s a complex life, living your life on the road. You’ve got to work to take care of yourself, which I don’t think a lot of those Beat Generation writers did very well. But there remains a romance of just traveling through.

One thing I’ve noticed about this record, though, is that there’s a lot of other voices singing with you. What do you like about that?

I love the human voice as an instrument. Just like instruments, every human voice is different and resonates differently. It affects a microphone differently. I think that voices singing in harmony can really elevate a melody. It adds a very important color to a record, for me. We did have a bunch of voices on this record. It’s a pretty magical sensation to be able to sing in harmony with someone. It’s like an electric jolt is running through you.

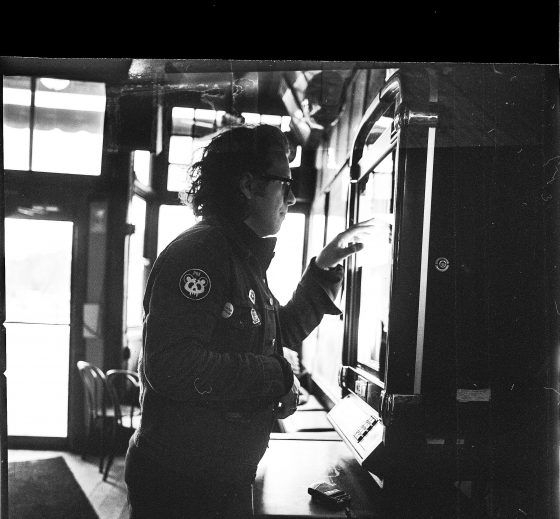

Photo credit: Chris Frisina