It started with Ranger Doug giving “A great big western howdy!”

It ended with Doug and compadre Too Slim harmonizing on “Happy Trails” and calling, “Head ‘em up! Move ‘em out! Hee-yaw!”

Well, how else would you expect a conversation with the two founding members of Riders in the Sky to be framed? That’s the Riders in a nutshell right there, these troubadours being dedicated to both the preservation and continuation of the rich traditions of cowboy music and celebrating life on the range. It’s a nutshell they’ve honed and inhabited over the course of four decades as the premiere (perhaps the only) purveyors of the form — not to mention the associated comedy schtick (one of those Old West terms) and embroidered, be-chapped and tall-hatted finery.

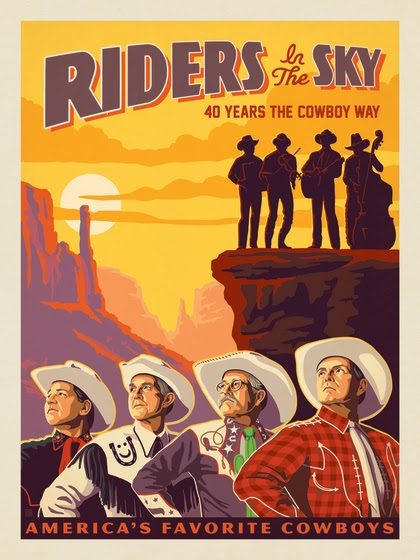

They are currently celebrating that time span with a new album, 40 Years the Cowboy Way, their 35th full release, a survey of the wide range (pardon the expression, pardner) and extensive history of cowboy music, from paeans to the prairies and rivers, to campfire songs, to jigs and polkas, to gunfighter ballads. There’s also a tour, which will soon bring their total career concert count past a whopping 7,300! It’s a legacy they never dreamed of back on that day in 1977 when guitarist Ranger Doug (known to some as Doug Green) first sat in with a bluegrass band that featured upright bassist Slim (a.k.a. Fred LaBour). Well, best — and most entertaining — to let them tell the tale.

“He was just Deputy Doug then,” Slim recalls. “He’d show up in a hat, play a Bob Nolan tune.”

“‘Song of the Prairie,’” Doug interjects. “You loved it.”

“I said, ‘Where’d that come from,” Slim says. “He said, ‘Bob Nolan.’ I said, ‘Did he write any others?’ He said, ‘Yeah, about 1200.’”

That, Slim says, was his introduction to the music of the Sons of the Pioneers, the Western swing-and-harmony group that featured Nolan and cowboy-star-to-be Roy Rogers. Soon, with the addition of Windy Bill Collins, they dedicated themselves to the traditions of the singing cowboys — Gene Autry, Tex Ritter, Rogers of course — and the Western ideal. Well, at least for one show.

That, Slim says, was his introduction to the music of the Sons of the Pioneers, the Western swing-and-harmony group that featured Nolan and cowboy-star-to-be Roy Rogers. Soon, with the addition of Windy Bill Collins, they dedicated themselves to the traditions of the singing cowboys — Gene Autry, Tex Ritter, Rogers of course — and the Western ideal. Well, at least for one show.

“I famously called Ranger Doug a couple days after our first gig and said, ‘I don’t know what happened back there, but America will pay to see that,’” Slim says. “It was so much fun, and it was music that had kind of gone from the landscape. The Sons of the Pioneers had albums in the cut-out bins and no one was doing what we were doing, so different and weird and entertaining.”

It was from one of those cut-out Sons albums, happened across by Slim, that the group took its name, and there was no looking back. With Collins leaving after a year (and replacement Tumbleweed Tommy Goldsmith staying just a year himself), Western swing fiddler Woody Paul (Paul Chrisman) came on board in 1978. Accordion wizard Joey Miskulin started working with them in 1988, becoming a full-timer soon after, squaring out the quartet we know today. Or as the Riders tell it:

“Woody joined us, bringing more original songs, a great tenor voice and that great fiddle style,” Doug says.

“And he can also fix the bus when it breaks down,” says Slim.

“That’s why we keep him,” adds Doug. “Not for his fiddle.”

“Not for his punctuality,” says Slim.

Doug continues, “Then about 10 years later we saw a guy on the side of the road with a sign that said, ‘Will Squeeze for Food.’ That’s how Joey joined us.”

Slim: “So that’s how we got a couple songwriters, a producer [Miskulin] and great players.”

“And Too Slim is being modest about his comedy skills,” Doug notes.

“I am objectively one of the second-funniest guys in America,” Slim says, with a modest level of modesty.

Soon the accolades, credits and, of course, fans around the world mounted up impressively: They were inducted into the Grand Ole Opry in 1982. They sang “Woody’s Roundup” in Pixar’s Toy Story 2 and contributed to the soundtrack of another Pixar film, Monsters, Inc., while their related albums, Woody’s Roundup: A Rootin’ Tootin’ Collection of Woody’s Favorite Songs and Monsters, Inc. Scream Factory Favorites each won them a Grammy Award for best children’s album. Also in animation, they were portrayed as a robot cowboy band in a 2003 episode of the animated Duck Dodgers, for which they sang the parts. In other media, they had their own Riders Radio Theater show and starred in a 1991 CBS Saturday morning kids show — kind of Pee Wee’s Playhouse on the prairie — which though not a hit, is pretty noteworthy nonetheless.

“About 10 years ago I said, ‘This has been way more,’” Slim says. “Two Grammys, getting to work with Pixar, the great venues and all the things we’ve done.”

Of course, even 40 years ago, this was already music of deep nostalgia. For that matter, when those singing cowboys and frontier heroes were doing it, it was already music evoking a bygone era — “the thrilling days of yesteryear,” as the Lone Ranger’s announcer put it.

How much of what they do is based on real traditions, how much on myth? Is there a core of reality to the music, or is it, in the parlance of pageantry, “folklorico?”

“That’s a complicated question,” Ranger Doug says. “The West had been glamorized and mythologized since the [James] Fenimore Cooper novels [notably The Last of the Mohicans in 1826], or [Owen Wister’s] The Virginian, at the turn of the 20th century. Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show was created while the West was still wild! There’s a whole tradition of romanticizing the West. Just so happens that it works musically. The great poets like Bob Nolan and Stan Jones and Tim Spencer were able to make it into song. Roy Rogers and his flowery shirts and six-shooter, that was not the real life of the cowboy in 1867.”

But, Slim stresses, “There was music in 1867. Folk music. A lot of Celtic, Appalachian songs to it, the whole blues thing. And when jazz happened it took on that element. So it became a melting pot, a gumbo of music, wouldn’t you say, Ranger Doug?”

“I would,” Doug says. “And the Mexican music, too, not only the songs but in costuming.”

And, Doug adds, “There’s a tradition of singing among working men who are isolated, in the days before they were on their iPhones. Sailor shanties and lumberjack songs and miner songs. These existed. So no surprise that there were genuine cowboy songs as well.”

“Some of these survive, and we do them,” Slim says.

Doug cites a few classics: “The Old Chisholm Trail,” “Red River Valley,” “Streets of Laredo,” “Bury Me Not on the Lone Prairie.”

There’s one, a little more obscure today, featured on 40 Years the Cowboy Way.

“‘The Blue Juanita’ was written in 1844 and was written about a river in Pennsylvania, which was the West to a lot of people then,” Slim says.

“It’s about an Indian maiden, plying her canoe up and down the Blue Juanita,” Doug says.

They do know their stuff.

“I wrote the book,” Doug declares.

“He actually did,” Slim elaborates. “Singing in the Saddle, the whole history from Fenimore Cooper to Riders in the Sky. A lot of emphasis on the Golden Era, the ‘30s and ‘40s when cowboy music was huge.”

The new album covers much of that ground. Surrounding “The Blue Juanita” are some expected, familiar songs (“Cimarron,” “Mule Train,” even Marty Robbins’ 1950s hit gunfighter ballad “El Paso”), some originals evoking classic styles (Green’s “Old New Mexico”) and some corny comedy (“I’ve Cooked Everything,” a food-centric rewrite of the Johnny Cash hit “I’ve Been Everywhere,” sung by craggy camp cook Side Meat, who may or may not be a LaBour alter-ego).

There are also what for some might be unexpected turns, including the jigs medley of “Pigeon on the Gatepost” and “The Colraine Jig” and the spritely “Clarinet Polka,” co-written by Woody Paul and Joey Miskulin, who, by the way, had a long pre-Riders stint with “Polka King” Frankie Yankovic. Oh, and some yodeling. There has to be yodeling.

Then there’s a Too Slim arrangement of the old traditional song “I’ve Got No Use for Women.” Talk about bygone eras. They are highly conscious of the fact that times, and attitudes, have changed, not just from the days of the real Old West but since the days of the Hollywood Old West, neither of which may have cast Native Americans and other non-Caucasian ethnic groups in the best light, not to mention women. It’s a touchy subject.

“Do you want to take that one, Slim?” Ranger Doug asks, gingerly.

“Go ahead, Ranger Doug,” Slim replies.

“At least two of us have some political views,” Doug says. “But we don’t bring them forth on stage unless we slip. We’re there to entertain. As far as the image of the cowboy, some people like John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart and Gene Autry were arch-conservatives, and that stuck. I think of cowboys as environmentalists, people who appreciate good behavior and preserve the beauty of the West.”

“We are of our time,” Slim says. “And what we foster is a good feeling, an escape in a way. But also a reinforcement of timeless values of contentment, sincerity, being true to your word and humor. And I think that’s why people still come back to our shows. They like the feeling we engender on stage. But I’ve got ‘I’ve Got No Use for the Women’ on the album, and it’s an old song and I do it in character. But in the #MeToo generation, I’ll be honest, I’ve thought about it. But it’s a valid song and performance and I think it works great. But we all recognize that there was part of the West that had to do with genocide, the underbelly of American history. We’re aware of that.”

However fine a line they may amble in that regard, however the image of the cowboy and the old times may have changed, whatever the Riders have done has worked for 40 years, people do keep coming to see them — at Bonnaroo, where they just played as part of a special Grand Ole Opry show, something they’d tried to make happen for 15 years, to Tokyo, at a tattoo convention in Maine or in the village of Anaktuvuk Pass, Alaska, well north of the Arctic Circle. Asked about the most memorably strange gig they’ve done, they cite that latter one.

“The whole town came to see the show,” Doug says. “All 40 of them, all Native Americans — Eskimos. They all brought their boom boxes and recorded the show.”

Slim adds, “And after the show we watched the Northern Lights, and I had a bottle of Southern Comfort.”

Whether riding off into New Mexico sunsets or the sitting under the Northern Lights, it’s been some mighty happy trails.

…until we meeeeet… aaaa…. gain.

Illustration: Zachary Johnson