When it came time to record his new album, Josh Ritter hired not only Jason Isbell to produce it, but Isbell’s band to play on the sessions. Because they had built a sturdy friendship while touring together, the resulting album, Fever Breaks, offers a familiarity that should appeal to fans of both artists. Longtime listeners may recognize that Ritter is more political than on his past albums – and that’s not a coincidence.

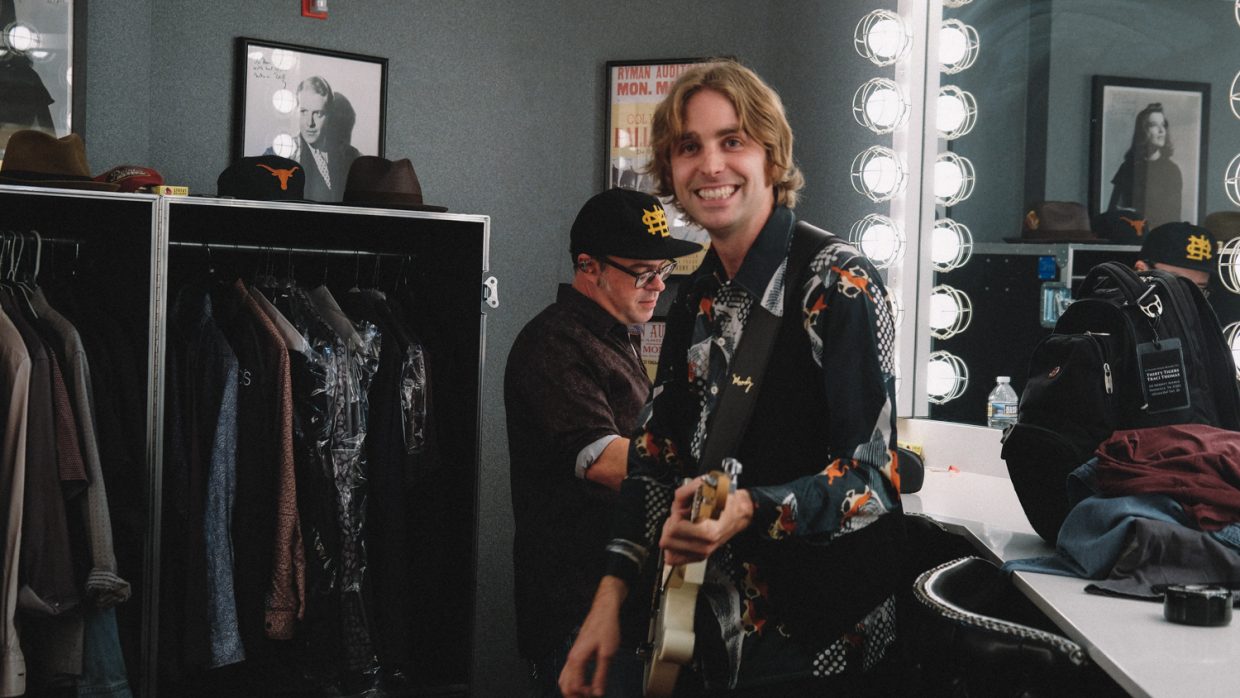

Leading up to a TV taping inside a cave in Tennessee, Ritter invited the Bluegrass Situation into his dressing room for a visit. (Read the first part of our interview.)

BGS: I caught a reference to “a fever broke” in the song “Losing Battles,” which I assume led to the album title. Why did Fever Breaks seem to fit as a title for this project?

Ritter: I love coming up with titles for the record. That’s one of my favorite things, because it’s a chance to look at the record you made from 30,000 feet and say, ‘What is it that sums this record up?’ With this one, it came to me in a dream. I just woke up with it, and I thought, ‘Fever breaks…’ I don’t know exactly what it means, but I thought with this project, so much of the writing was guided by instinct, and I felt like it was important for that dreaminess to come in.

It really feels, in a certain way, like a comforting thing – even though I feel like the record is not comforting. It’s a reminder that fever will break, and that’s as close as I can come, because the period that we’re living in feels so overheated and so full of chaos, that it has to be a sickness.

What’s your response if someone hears this and says, “Oh, Josh made a political album.”

I would say I would be thrilled! I think it’s important, right now. I don’t know how you could make music, or anything, that doesn’t have this time wrapped up in it. Like some kind of weird, dark rhythm. It’s just everywhere in the whole tapestry of things, and how do you speak about anything in our lives without referencing this period of time?

One of the great things about making records over a period of time is that they feel like little vials of perfume from that moment, you know? You open it up and you remember. I remember where I was when I was making The Animal Years, and for me, this record will always be wrapped up with this strange, dark moment, and I have to express that on the record. And if it comes across as political, that’s great. I hope that it doesn’t come across as anything else.

So much of someone’s success in the music business comes down to who you surround yourself with. Why was it important for you to bring Jason and Amanda [Shires] to this project?

I think for a long time, I lived on an artistic island that was self-imposed. Just from being busy all the time and touring all the time, I started to realize that my circle of friends – while very tight and incredibly close-knit – was very small. And around this time, I went on the road with Jason and Amanda and the 400 Unit, and I got a chance to see that there are other families on the road, and there are other people touring with their families.

I felt a sense of connection through shared choices, artistically and just how he was choosing to life his life. There was a kinship that I felt was artistic and personal. So when I identified that I wanted to work with somebody, like a peer, he jumped into my head. I sent him a note and I was really so surprised and happy when he was into it, and when we could schedule the time to do it, which was an impressive feat.

How long was the email you sent?

Just a few sentences. And my initial idea was that he would produce, but that I would bring people to play. So I was really excited and nervous when he suggested the 400 Unit because they’re amazing players and I didn’t know what it would be like to not play with my band. So I had frank conversations with everybody in my band. I was overwhelmed that they were so supportive of me going to do this crazy thing.

I think it’s just so cool that you can play music with people for so much of your life, and work so hard on things, and then they understand that I’m going to go off and try this thing and take this chance. Because I feel so close to them, it’s really important for me. So once I talked to the band, I embraced the whole philosophy of going in and realizing that I wasn’t going to know anybody very well.

You’ve worked with some legendary figures like Joan Baez and Bob Weir. They’re in their 70s, still creating music. Do you see a similar trajectory for yourself?

I hope so! The main goal is that your mind doesn’t get smaller as you work, and that your neurons are always branching out. … I learned so much from working with Bob and Joan. What brought me into this world of working with Jason was that I had to learn how to collaborate, and listen to how my portion could fit and work with somebody else’s artistic vision. It was super cool to work with them and learn that.

You have to trust yourself in that situation, too.

Yeah, and trust that what you’re bringing is worthwhile, and trust that what they’re bringing also has its own [value], and these things are going to intermesh in ways that you can’t expect. That’s just amazing! You get so few opportunities for those unexpected, great musical moments that you just cherish.

When I was looking back on your discography, I realized that this is the 20th anniversary of your first record. What do you remember about making that decision to go into music full-time?

Well, my parents are both scientists, so I grew up around an academic structure in my family. I saw how it worked when you went to college, and then went to graduate school. So I approached making a career in that way. I said I’m going to need everybody to trust me for four years, and we’ll see if it can happen. I remember I quit my last temp job in 2004 and I realized I had no Plan B of course. I wasn’t particularly good at anything. What I loved was songs and it was all I could spend my time thinking about. I remember the first time getting money out of an ATM to buy gas and go on my first gig – and what an exciting moment that was. I didn’t realize it at the time the same way I do now. It was so exciting!

You’ve built an international audience since that time. Was it always a goal for you to be a world traveler?

I think so, yeah. I think I got into it for the traveling. A lot of people get into it for the traveling. I have found that music takes you to the most incredible places, but also it takes you to some places that are incredibly mundane as well, you know? They can’t all be caves in Tennessee, but that’s fantastic for that reason.

Photo of Josh Ritter: David McClister

Illustration: Zachary Johnson