David Grier gets asked all kinds of questions.

He’s asked about his phenomenal cross-picking guitar techniques, which put him among the greatest bluegrass/folk players of the last several decades, talked about in the same breath with Doc Watson, Clarence White, and Tony Rice.

He’s asked about his dad, Lamar, who played banjo with Bill Monroe. Yeah, that Bill Monroe, the Father of Bluegrass.

He’s asked about Clarence White’s brother Roland, the Kentucky Colonels mandolinist who was an early teacher of his. And of course he’s also asked Clarence, Grier’s big influence, who brought bluegrass guitar into the rock age with the Colonels and then, on electric guitar, powered early country-rock with the Byrds.

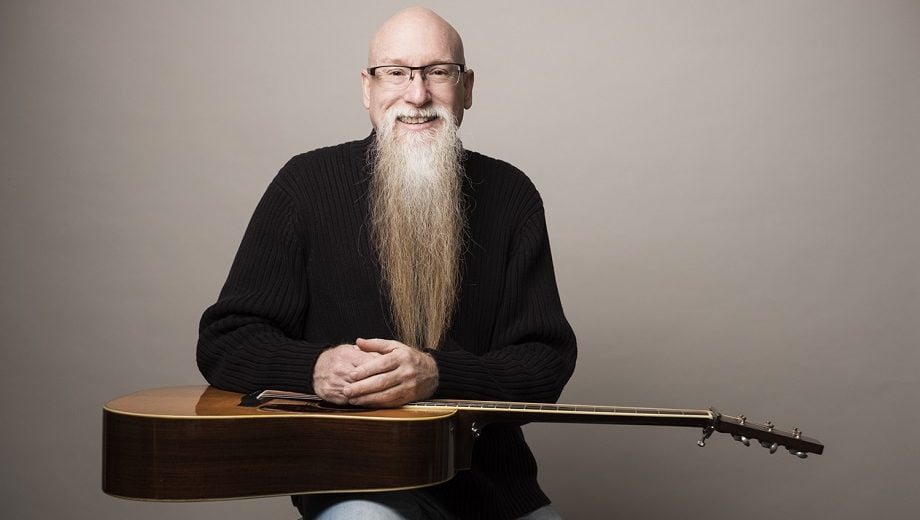

He’s asked, maybe too much, about his beard, a prodigious gray broadsword of whiskers stretching from chin to navel, an abstraction of which is the signature feature of his silhouette, featured on his T-shirts and other merch.

But one thing the D.C.-raised, Nashville-based musician is never really asked about: His singing. And for good reason. He’s never done it.

“It’s always been, ‘Why don’t you sing? You play guitar!’” he says, an irrepressible joviality marking his droll drawl.

Somehow, he sighs, people often seem to think that simply because he plays guitar he ought to sing too.

“I know I play guitar,” he says, more amused than exasperated. “I never donated any time toward [singing]. I tried once or twice through the years. Just like anything else, I gave it five or ten times and stopped.”

Until now.

His new album, Ways of the World, features five songs with him on lead vocals. That’s a first. In his career going back to the early ‘80s and covering ten solo albums now, several side projects (Psychograss, Helen Highwater Stringband), and hundreds of guest spots and sessions, he’s never stepped out as a vocalist before.

And in a rather bold move, he puts his lead vocals alongside some noted vocal talents: Maura O’Connell, Tim O’Brien, Shad Cobb, Andrea Zonn, and Mike Compton. What’s more, he’s feels pretty good about it.

“I do,” he says. “I know later I won’t, because every time I think something’s perfect, I listen to it later and go, ‘Gee, why didn’t I hear that before?’”

So the next question comes naturally: “Why now?”

“It was the Helen Highwater Stringband,” he says. “Three or four years ago they said they needed another singer for a vocal trio. They looked at me. I said, ‘I don’t sing!’ They said, ‘You do now!’ I went, ‘Wow.’ They were encouraging. It was helpful. All that went into account and then I did it on stage. People weren’t running for the exits, so this is good. And it just kept going.”

If he was going to sing, he needed words, and he dove right into that as well. Songwriting was another new challenge.

“I’d written the first two lines: ‘I’m afloat on the great big waves of the ocean, I drift on the ways of the world,’” he says of the title song, with Zonn singing with him, which opens the album. “I thought, ‘Hell! That’s going to be a song!’”

But he thought he’d need help and, while heading out for a five-and-a-half-week tour in South Africa, he went to a friend to have him finish it. That didn’t happen. So with two off-days he set to it himself.

“I finished it in an Airbnb on the beach in South Africa,” he says.

It was a whatever-it-takes approach to songwriting. “Dust Bowl Dream,” with harmonies by O’Brien, came from a bar bet for a round of drinks with some Nashville buddies as to who could write the best song in a week.

“I wasn’t even going to write a song,” he says. “Thought I’d just buy drinks for the buddies. But I had this melody that was lonesome and I thought, ‘Well, dust bowl is lonesome.’ Wrote the words in an airport, wrote the verse, chorus, second verse. I thought it was great. Got to the hotel later that day and started playing. First verse was great, second was great, last verse was horrible! I wrote another and that was worse. I went back to the first version I wrote and thought, ‘If I don’t sing it, that’s great.’ So I talk through it, like Bill Anderson would. It’s a recitation, and I think it really helped the tune. You feel it more.”

Now, all you who savor every splendiferous Grier guitar lick, dread not. The five songs featuring vocals are accompanied by eight sparkling instrumentals, and the ones with singing also feature, of course, his spectacular picking.

The heartfelt vocal numbers are surrounded by a selection of wryly titled original picking showcases (“Waiting on Daddy’s Money,” “The Curmudgeon’s Gait,” and so on) and sparkling interpretations of, or variations on, old fiddle tunes (“Billy in the Lowground”). And playing with Grier is a stellar cast of associates: a core of Casey Campbell on mandolin, Stuart Duncan on fiddle, Dennis Crouch on bass, with John Gardner on drums for some songs, and banjo from Justin Moses and Cory Walker. What’s more, there’s electric guitar by Bryan Sutton on one song (“Dustbowl Dream”) and on “Farewell to Redboots,” there’s trumpet by Rod McGaha — something perhaps even more surprising than Grier’s singing.

“For me having a trumpet on a song is brand new,” he says. “I just heard it in my head that way and imagined it that way. But having it happen was amazing.”

The whole experience, it seems, was liberating in a way that led Grier to try some different approaches to his picking, as if the pressure was off to make the album completely about that. The result is a rich, engaging tone throughout.

“I think on this record there’s less flash, just for flash’s sake,” he says. “Less, ‘Watch what I can do! Watch! This is hot!’ This is more reined in for a bit. Some of the solos are simplistic, and in my mind harken back to the beginnings of bluegrass music.”

He cites the intro to one song, “Dead Flowers,” an original, not the Rolling Stones song.

“That’s as basic as you can be,” he says, noting that it happened that way in the moment when he was caught off guard. “I got in the studio and thought someone else would kick it off. ‘Who’s gonna kick it off?’ Crickets. ‘You start it.’”

On the other hand, he also found himself spontaneously taking some other unexpected directions in “Red Boots.”

“There are three solos in that,” he says. “First one of me, then the horn, then me again. The first one’s just the melody, nothing fancy. The melody is cool. But the last solo is completely different, a little bit of Wes Montgomery, some string-bending in there. Just popped out! I’d never played that before. Every time I’d played that song it was just the melody, ‘cause I’m generally sitting here playing by myself. In the studio it was, ‘Well, I’ve done that. I want to do something different.’ I like that. Fresh and exciting. Note by note. Not the boring same old thing.”

And that’s the thread of the whole album.

“A lot of improvisation on this record,” he says. “From my viewpoint, it’s playful. All in the vibe. Not some hot lick thrown in just to show I can play a hot lick.”

Not that he isn’t proud of his playing here.

“There’s things in there people might want to learn when they hear it,” he says.

And speaking of learning, one more question: Has he ever tried fingerpicking?

Grier sighs.

“That’s another thing maybe I gave five minutes.”

Well… given what he said about singing, stay tuned for the next album.

Photo credit: Scott Simontacchi