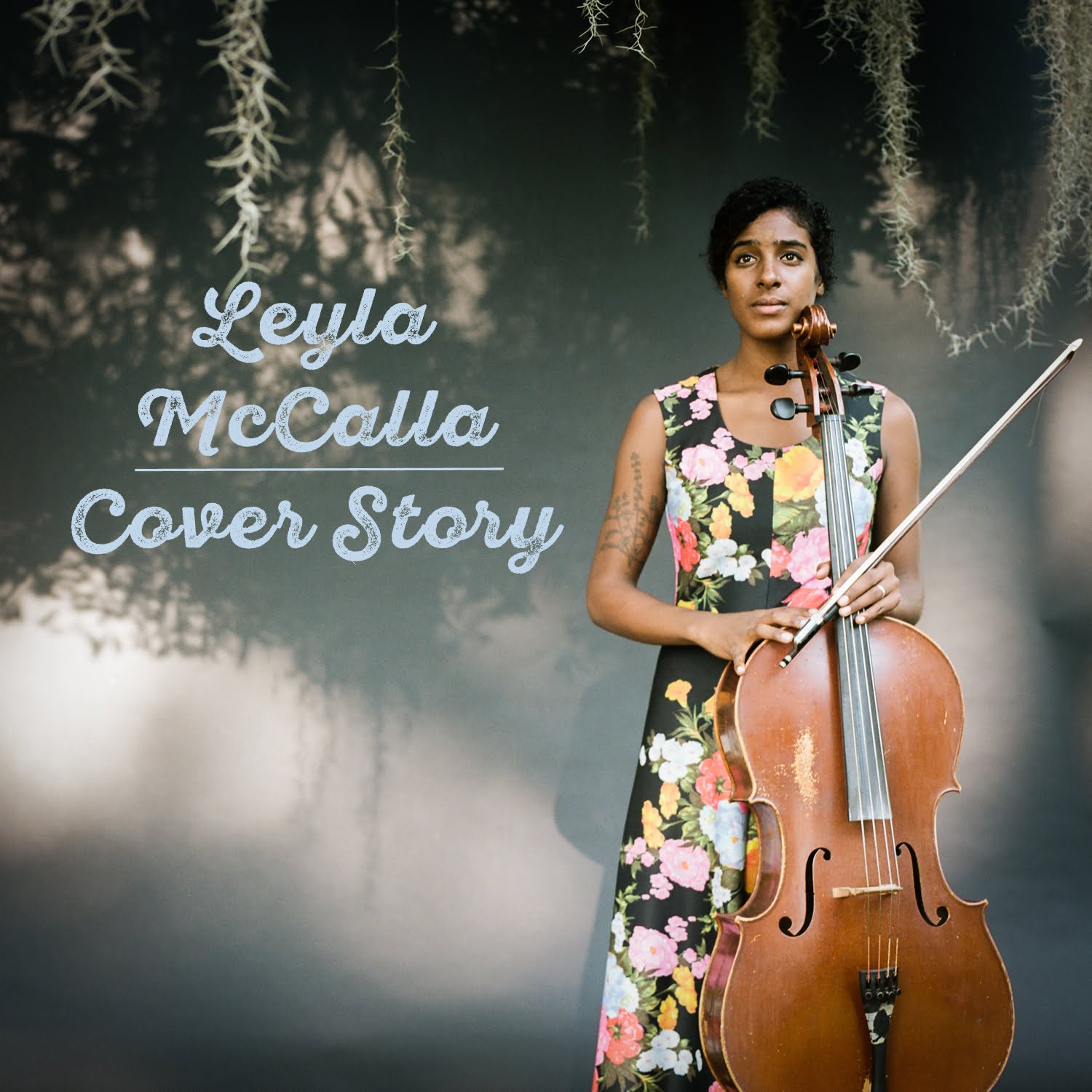

(Editor’s Note: Cellist, composer, and creator Leyla McCalla brings us a conversation as guest contributor with singer and community activist Barbara Dane – in celebration of her 96th birthday on May 12.)

I felt an immediate connection to Barbara Dane when I heard her voice. I first learned of Dane while developing music for a FreshScore – a commissioned piece written to a film in the public domain to be performed at the Freshgrass festival back in 2018. I had just given birth to my twins and I found myself researching songs to use in my score. During that time, I came across a civil rights era song called “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” that Dane had released with a group called the Chambers Brothers in 1966. I fell in love with the recording – the performance was powerful and poignant; the message was so direct.

Some songs just make you want to learn them. Freedom is a constant struggle. A perfect and ever true statement. It inspired me to write a song I called “Trying to Be Free” that became one of the songs in my FreshScore. I dug further into Barbara Dane’s catalogue and found a song that she had written called “I Hate the Capitalist System.” This felt very in line with the themes in my (at that time) yet-to-be-released third album, The Capitalist Blues. This is the epitome of the “folk process,” a phrase I jokingly use when talking about songwriting. You think you’ve found a unique idea, only to find that the idea has existed since time immemorial. The road that is paved with gold keeps on getting mined, refilled, and recycled and on and on.

Years ago, a friend suggested that I check out the song “Dodinin” by Atis Indepandan – a group of Haitian artists living in exile in New York City from the brutal Duvalier dictatorship in Haiti. The album is considered a classic within the Haitian diasporic community. When I was doing research for Breaking the Thermometer – the album I made inspired by Radio Haiti and the legacy of its journalists – I found myself more deeply exploring the songs. I’ve never been more grateful that Smithsonian Folkways has downloadable liner notes on their website! And beyond that, I was grateful that the liner notes were so thorough; it included essays on the political context of the music as well as Kreyol and English Translations of the songs. The songs spoke to the struggles of the times and longing for home of Haitians in exile. It is hands down one of my favorite pieces of art ever made. I knew I had to include Dodinin on the record.

Fast forward to the release of the album, Barbara Dane’s son, Pablo Menendez, emailed me. He was curious about whether I was aware of his mother’s legacy and if I knew that the album was originally released on Paredon Records, the label that Dane cofounded with her husband, Irwin Silber. Paredon Records was not a typical label; all of their releases highlighted the political struggles of people from all over the world with a mission to uplift movements and voices of opposition to oppression. He also mentioned that I should read her newly released autobiography, This Bell Still Rings, and I immediately ordered it and began to read her fascinating life story. I was even more amazed when I looked at the inner flap of the hardcover and saw that my name was mentioned as one of the inheritors of her legacy! It was a very life affirming surprise. How did I not know?!

I worry that we are living in a time of tragic disconnection. As musicians, we are constantly being pushed towards releasing a steady stream of “content” to get more views and more likes, more money, and more recognition. But, often times that comes at the expense of our health. I mention this because I feel that more people in our musical community should be aware of the music, ideas, and ethos of Barbara Dane. She is someone who has always centered the needs of the community, locally and globally. She doggedly worked to understand the causes behind the stratification of our society and gracefully occupied so many roles to be able to use her creativity for the greatest good for herself, her family, and others. As a mother of three myself, I was very curious about how she did it! Whether you realize it or not, we need Barbara Dane right now – if nothing else, to remind us of our essential power when we center community care.

Reading her memoir and seeing that Dane’s 96th birthday was coming up (it was May 12, 2023), I felt inspired to do something to mark her birthday. I remember thinking to myself, “Let’s celebrate our heroes while they are still here!” I released a cover of her song “Freedom Is a Constant Struggle” alongside a cohort of collaborators from my adopted home of New Orleans. My manager suggested that perhaps we could arrange an email interview and I was ecstatic when Dane graciously replied with a yes.

I am incredibly pleased to share the interview with you here on BGS and I hope it will inspire you all to think more about the potential we all have to take better care of each other. This bell still rings!

Leyla McCalla: I have been reading your new autobiography, This Bell Still Rings. What does this title mean to you and what do you want readers to understand from it?

Barbara Dane: The title is taken from a lyric by Leonard Cohen which I will quote for you:

Ring the bell that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There’s a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

What I’d like readers to take from that is that the imperfections in things are what offer possibilities for learning and growth.

How did your early experiences of blending music and activism shape your career? Was there any particular moment where you felt that this would be your life’s work?

I never thought of myself as having a “career,” I guess my professional work grew out of the need to put food on the table. As far as blending music and activism, early on it became clear that my voice was a valuable tool for my community work. I was lucky enough to be exposed to movements like People’s Songs that allowed me to see the possibilities at a young age. The artists that influenced me the most in this regard during my formative years were Paul Robeson and Pete Seeger.

Who do you cite as some of your earliest teachers and/or influences to your musical approach?

Early on I was exposed to the music of Billie Holiday and Louis Jordon and of course the big bands so popular in the 1940s, like Ellington, Basie, and Glenn Miller. Earl Robinson’s famous “Ballad for Americans” was foundational. And definitely such giants as Paul Robeson, Leadbelly, Pete Seeger, and Malvina Reynolds, and later, the blues women of the 1920s and 30s: Bessie Smith, Ida Cox, Ma Rainey, and Sippie Wallace. And of course there was my beloved Mama Yancey.

Your vocal phrasing is incomparably gorgeous; it feels both so natural and so intentional. When did you realize that you had a natural gift and was your craft something that you worked on intentionally, or something that came naturally, or both?

Listening to Louis and Billie taught me that you don’t have to stick to the bar lines. I was more comfortable with the conversational feel of their phrasing. Once you understood the structure of the piece, you can be free within it. So no, I never worked on it and none of it was intentional. My intention has always been to be completely in the song and let its emotions and meanings lead me.

You opened a music venue in 1961 called Sugar Hill. It sounds awfully stressful to run a music venue while raising small children! Can you share more about how that came to be and that time in your life?

Actually, on the contrary, the whole idea of opening the club in our hometown, was it that it would allow me to spend more time with my family instead of always being out on tour. Running the club was a joy and gave me the opportunity to introduce some of the old timers who had more to give to a new audience that was just beginning to become interested in the blues.

Who were the Chambers Brothers and how did you come to collaborate with them?

They were four talented brothers, recently migrated from Mississippi to LA, who had formed a gospel group and were looking for ways to broaden their audience. I first met them in 1960 when I invited them up to the stage at the Ash Grove to join me in singing some of the songs that were emerging from the civil rights movement.

You were the first U.S. artist to tour in Cuba after its revolution. What was the impact of that experience on your life?

Going to Cuba in 1966 changed my life. I was energized by the optimism of the Cuban people as they engaged in building a new and more equitable way of life. For the first time I felt identified with the direction society was moving in, whereas at home I was always in the opposition.

Paredon Records is the label you founded with your husband Irwin Silber in 1969. What made you want to start a record label and produce albums?

In 1967, I attended Cuba’s Encuentro de Canción Protesta where I met singers from all over the world who were deeply committed to struggles for peace and justice. When I returned home, I felt the urgent need to expose the U.S. public to the significant and timely music I heard there. First I experimented with translating and singing some of the songs myself, but I soon realized it would make more sense to present the original voices. So I decided to launch a record label. Irwin had skills to bring to the table from his years of experience in publishing, and with his support, I produced and curated over 50 LPs of liberation music from the U.S. and around the world. Eventually, to ensure the collection’s availability in perpetuity, we donated it to Smithsonian Folkways.

You’ve toured internationally, including Franco-era Spain, Marcos’ Philippines under martial law, and North Vietnam under the threat of American bombs. What inspired these tours and why did you feel they were important places to bring your music?

With my international work I carried a message of peace and anti-imperialism, representing the sentiments of peace-loving Americans.

I’m also a mother of three and I find myself in awe of how much you were able to accomplish in your life while also raising your three children. How did you balance your musical life, activism and child rearing? Do you have advice for artist parents on how to navigate it all?

Be sure to include your children in all aspects of your life and help them learn to be independent. Trust and respect them. Make sure your partner is willing and able to actively do their share of the parenting.

Sometimes it seems that peace and justice are impossible to achieve. What would you say to people who feel that they do not have the power to make a difference?

As expressed in Beverly Grant’s moving song, “Together, we can move mountains. Alone, we can’t move at all!”

Photos courtesy of Leyla McCalla (by Laura E. Partain) and Barbara Dane.