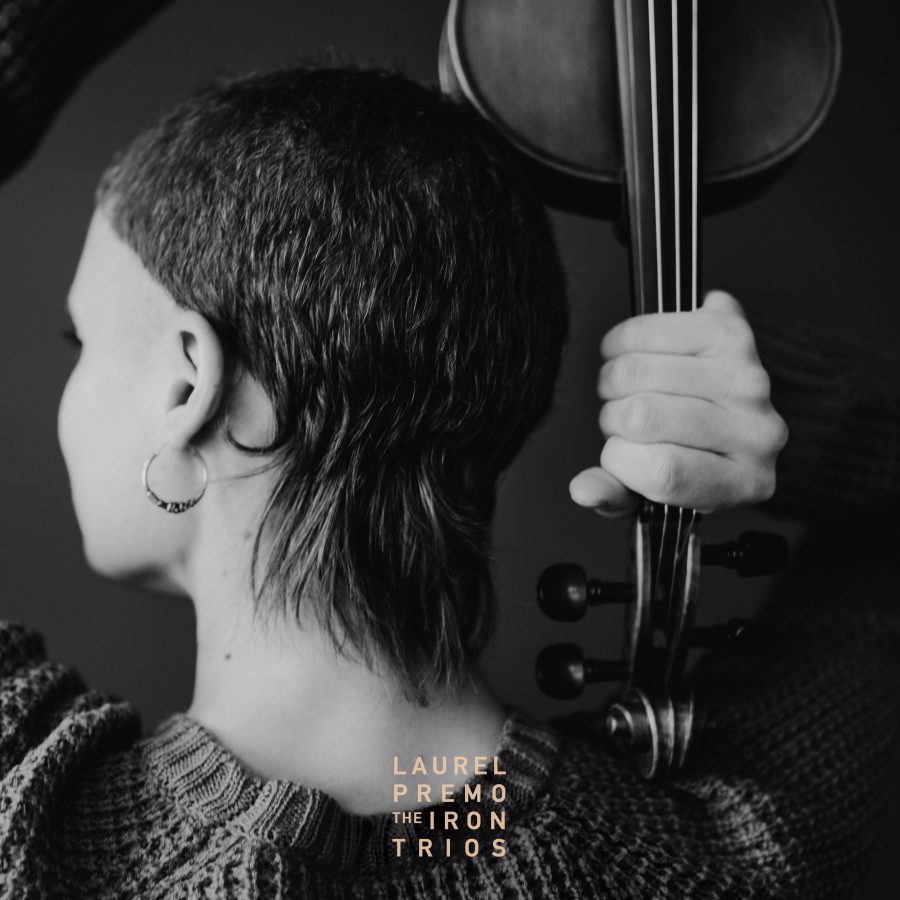

Artist: Laurel Premo

Hometown: Traverse City, Michigan

Latest Album: Golden Loam

What other art forms — literature, film, dance, painting, etc. — inform your music?

For me dance is such a huge influence. I’ve spent quite a few years as a dance musician for square dances, being a traditional fiddler. That role of being more the motor for the good time, as opposed to being the focal point, has always resonated deeply with me. But beyond that, I know that just my experience as a participant in social dance in both American old-time and Nordic traditions has given my body a vocabulary that comes out in my music. I’ve found a through line in my voice that, no matter the tempo of the music, I always am wanting to make these larger slower pulses, make longer groups of beats, tap my foot at a slower frequency. I’m certain that that longer embodiment of phrases, and the pull, and balance, from dance have played into my nature there.

What was the first moment that you knew you wanted to be a musician?

I have a really early memory, I’m not sure what age, but before I was big enough to hold any instruments. I was in my bedroom, standing next to the door, and I could hear my folks playing music on the other side of the wall in the living room, my mom really tearing it up on some fiddle tune. In that moment, alone, I remember that I started air-fiddling and kind of marching around or dancing in the little corner. I just wanted to be part of whatever was going on there.

What’s the toughest time you ever had writing a song?

I took a while composing this lap steel track, “Father Made of River Mud,” from the new record. For a bit, it was separate pieces, in different tunings, that I didn’t know if I’d be able to fold together as one. It’s a really beautiful moment for the maker of a piece, when some kind of grace math helps everything line up in your head, and then you get to hear the thing for the first time in its full form. That tune is like a circle, it doesn’t really have to end at any one point.

What rituals do you have, either in the studio or before a show?

I try and spend some time ruminating with memory that reflects back at me the elements of my personal experience that I want to embed in the performance, to make more vibrant what I’m laying down there for listeners. It’s almost a way of remembering myself to myself, because there are a lot of possible distractions when you’re recording or performing. Every little step of the setup could be something that takes you away from your body and the meaning you’re trying to imbue in the work. So, I just real quickly try to go into the wilds to try and counteract all of the civilization that I’m traversing through.

Which elements of nature do you spend the most time with and how do those impact your work?

In the last two to three years, my wild haunts have been woods, dunes, and rivers. I grew up in the woods, so shadows and green, what reverb the places with a great amount of life growing have, and the scents of being real close to the ground — those are all deep in me, and as an adult I go back to similar places to find quiet, and to kind of listen beyond that quiet. Walking rivers for the past few years, learning fly fishing, has brought about a whole other set of turns, including just a beautiful sideways weight from the gravity of the river flowing against you. I definitely take gestural impulses from my time spent in the wild, and work to keep all my senses open to what rhythms lay in front of me.

Photo credit: Harpe Star