Well after midnight on Thursday at World of Bluegrass in Raleigh, North Carolina, Molly Tuttle and her quartet took the stage of the Lincoln Theater for a surprise show. The room quivered with anticipation because, a few hours before, Tuttle had been named the IBMA Guitar Player of the Year — the first woman to ever be nominated for the prize.

Women have won in the instrumental categories of banjo, bass, fiddle, and mandolin (Sierra Hull earned her second trophy on the same September night). But lead guitar felt like a bluegrass Rubicon. Weighing against Tuttle, and fellow feminine flatpickers like Courtney Hartman and Rebecca Frazier, are decades of societal coding of guitar in rock ‘n’ roll as a phallic proxy for masculine sexuality. But even beyond that, the bluegrass world, as good as it’s been cultivating its youth, has strongly suggested that girls coming of age should play rhythm and sing. Playing machine gun solos a la Tony Rice or daredevil cross-picking like David Grier seemed anathema for way too long. Where there reasons for this? Anything physical, emotional, or intellectual? Uh, no.

Tuttle’s win coincided with a few other signifiers of progress in the long slog toward full inclusion for women in the music. Hazel Dickens and Alice Gerrard were inducted last week (belatedly) into the Bluegrass Hall of Fame. A smart display in the foyer of the Raleigh Convention Center depicted the history of women in bluegrass, from Sally Ann Forrester to Alison Krauss and the abundant riches of today’s scene.

Feminism was bluegrass music’s first go at civil rights and inclusion, and it took a long, grinding time to arrive at something resembling parity in the modern world. As Murphy Hicks Henry points out in her 2013 book, Pretty Good for a Girl: Women In Bluegrass, one early scholarly work on the genre literally defined the bluegrass band as “four to seven male musicians (Henry’s emphasis) who play non-electrified stringed instruments.” And that was after Bessie Lee Mauldin played bass for Bill Monroe for eight years. Henry’s definitive history set out, she wrote, “to lay that tired myth of bluegrass being ‘man’s music’ to rest. Bluegrass was and is no more ‘man’s music’ than country music was ‘man’s music,’ than jazz was ‘man’s music,’ than this globe is a ‘man’s world.’”

Carry that to its logical and uproariously banal conclusion, and one might dare to propose that bluegrass is everybody’s music. And, in fact, that premise is being put to the test nationally, including in the hothouse environment of IBMA. The most pressing issue and exciting conversations at World of Bluegrass 2017 were about inclusion and diversity in a genre that has, for decades, presented an almost uniformly white, straight, Christian face to the world. Ain’t nothing wrong with any of those things. I’m two of them and love many who are all three. But that is clearly not everybody, and it would be cool if LGBTQ+ people and people of color could, you know, skip ahead to the good part without the decades of hand-wringing and foot dragging that women endured. Hazel & Alice didn’t go the distance for themselves alone or for women alone, after all. They bid the stranger, per the Carter Family, to “put your lovin’ hand in mine.” They sang for the marginalized, all of them.

Alice Gerrard, flanked by Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer, at Shout & Shine

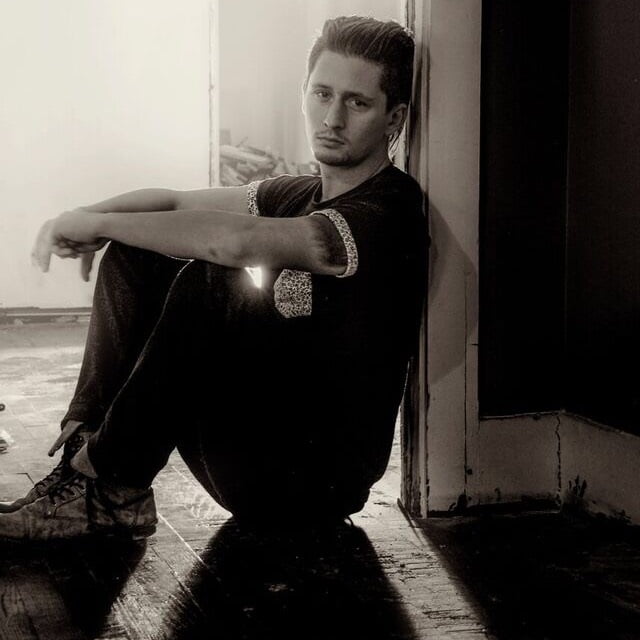

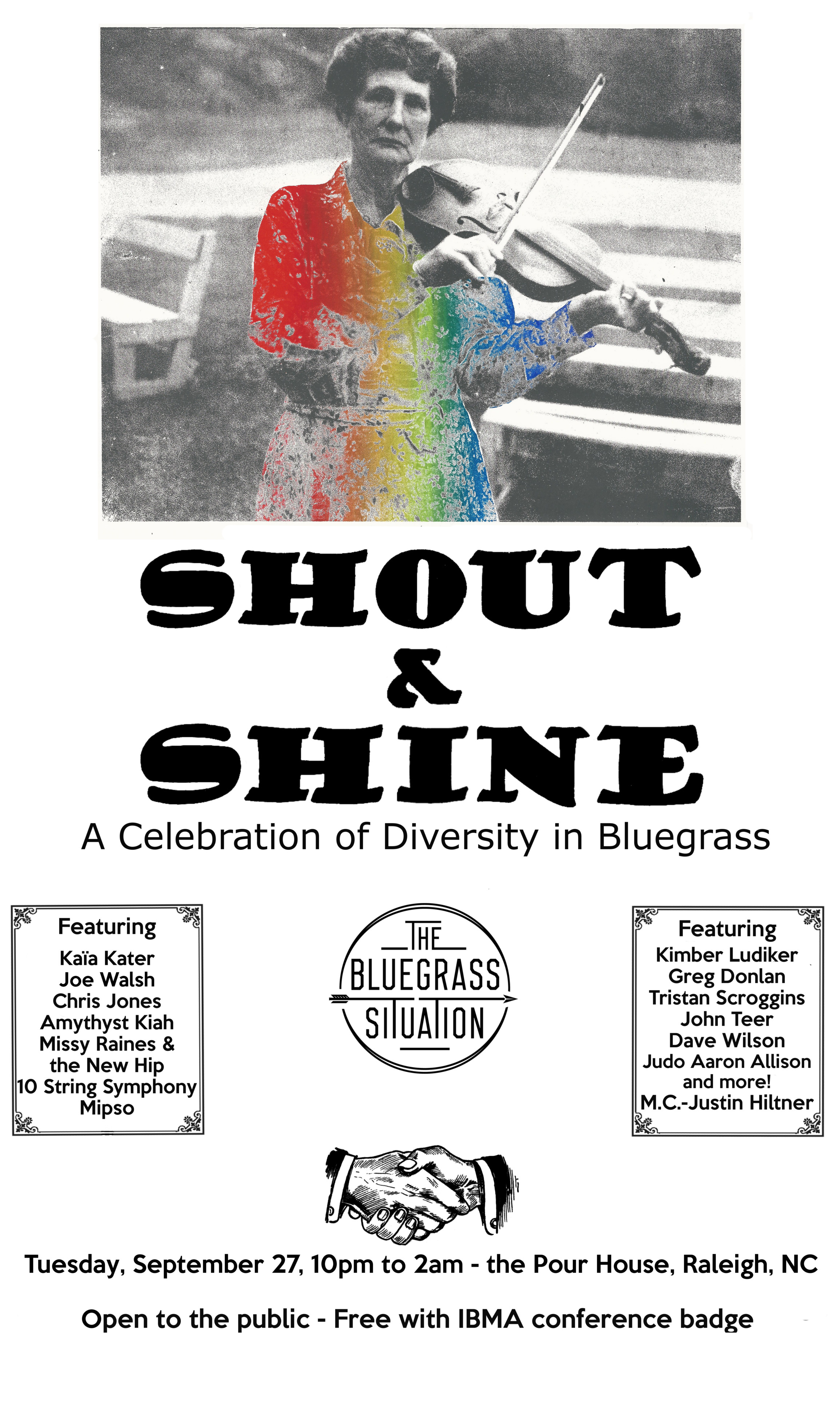

Over the past 12 months, the inclusion movement has been on a forward roll. The most talked about event at the 2016 IBMA convention was the semi-sanctioned, upstart Shout & Shine diversity showcase, with musicians who were Black, brown, and queer throwing down on banjos and fiddles. If any one thing put a new face on bluegrass music in modern times, it was this. Organizer Justin Hiltner (the BGS’s social media director) stepped up in a leadership role, not only by example as an openly gay banjo-playing dude from Nashville, but by challenging the IBMA institutionally and professionally to be explicitly and publicly inclusive, or risk leaving new generations of potential members uninterested.

Minor controversy broke out last spring when members of the California Bluegrass Association sponsored a float in the June San Francisco Pride Parade. A thread on the association’s forum is full of respectful conversation and overwhelming support for putting a float with a live bluegrass band in one of the Bay Area’s biggest public gatherings. While there seem to be no reports of outright hostile homophobia, a minority of the membership took the more oblique path of objecting to their music and association being tied to “religion and politics.” One fellow wrote, “I see the gay pride parade as a promotional event for the gay lifestyle and the in-your-face display of that lifestyle.”

The CBA contingent went ahead, of course, and besides having a triumphant day, the float went on to win the SF Pride Best of the Best Overall Award, the highest honor for Pride participants. In the end, a small handful of people resigned from the CBA, but even more appear to have joined. And Bluegrass Pride’s rainbow forward t-shirts and buttons became the hot thing to wear at Raleigh’s World of Bluegrass.

Likewise, this year’s second Shout & Shine concert was a hit, with performers that included the African-American string band the Ebony Hillbillies and openly gay Kentucky folk singer Sam Gleaves, plus his mentors, married folk duo Cathy Fink and Marcy Marxer. Gleaves told me he found the event “heartening and really fabulous,” but this most humble gentleman tends to emphasize the aspirations of others more than his own identity, be it a more prominent place for people of color or old-time folk music itself.

Melody Walker, whose band Front Country led the show-closing super jam, said that the “Shout and Shine showcase was the most diverse stage and audience I’ve ever seen at IBMA. It was really beautiful and it kind of feels like a window into the future of what IBMA could be, if we express love and openness to the world and let people know that it’s safe to fall in love with bluegrass and they have a place here.”

Justin Hiltner and Sam Gleaves join Front Country for the Shout & Shine super jam

I kept looking for somebody to break out in hives. Because, seriously, people in bluegrass will do that over the wrong kind of banjo tone ring. But even amid the hustle and bustle of the convention center and town hall meeting, I heard not a discouraging word. Somehow, with a mixture of diplomacy, facts, humanity, and appropriate assertiveness, the Bluegrass Pride movement made its impression and the ecosystem took it in stride.

Likewise, for the Thursday afternoon keynote address by Rhiannon Giddens, founding former member of the Carolina Chocolate Drops and the 2016 winner of the Steve Martin Banjo Prize. IBMA officials who conceived of and worked on the invitation described some board members as wary, for reasons that are hard to discern. Nobody went public. Nobody’s come up to me and said, “What’s she doing here?” But was IBMA truly ready for an authoritative African-American figure with a major label deal, an acting role on CMT, and other high-profile platforms to come to their stage and talk candidly about bluegrass and race?

Apparently so. Reaction to the Tuesday afternoon speech was, spitballing here, 90 percent rapture and 8 percent relief. (I’ll assume 2 percent unspoken upset or non-attendance.) Sounding for all the world like Barack Obama, with her biracial family story and her sense of only-in-America (for good and otherwise), she spoke of bluegrass music as honestly and completely as I’ve heard it told. I expect that fans, musicians, and scholars will replay and review its layers for years to come because it was dense with truth and a powerful revision of our standard origin story. She offered her own account of growing up in and near Greensboro, North Carolina with a white uncle who played bluegrass and a Black grandmother who simply adored Hee Haw. Her carefully documented recounting of Black string bands and the appropriation of the banjo were full of similar counter-intuitive revelations.

“In order to understand the history of the banjo and the history of bluegrass,” she said, “we need to move beyond the narratives we’ve inherited, beyond generalizations that ‘bluegrass is mostly derived from a Scots-Irish tradition with influences from Africa.’ It is, actually, a complex Creole music that comes from multiple cultures, African and European and Native — the full truth that is so much more interesting and truly American.”

This was the wind-up to the line that’s been most widely quoted, the thesis sentence, if you will: “Are we going to acknowledge the question is not ‘How do we get diversity into bluegrass?’ but ‘How do we get diversity back into bluegrass?’” This line resulted in one of a half-dozen of rounds of mid-speech applause that led to the ultimate standing ovation.

Member of Bluegrass 45 lead the Japanese Jam

For years, my joke about bluegrass is that it’s very diverse. It attracts all kinds of white people. The serious sentiment behind that veil is is my early and ongoing impression that, besides being an exciting and powerful musical form with an American heartbeat, bluegrass attracts what pundit and podcaster Ana Marie Cox calls an “uneasy coalition.” Bluegrass festivals are one of the rare places I’ve seen rural Red Staters and urbane Blue Staters enjoying life and mingling together. The scene is somewhat like Willie Nelson’s ecumenical shows of the 1970s, with Christians and hippies and farmers and nerds. This variety show can also be found in sports, but frankly at NBA or NFL or MLB contests, you can easily arrive, cheer, and leave without engaging with anybody not of your tribe. In the musically charged environment of bluegrass, that’s far less likely. We go to church apart. We vote apart. But we all love Flatt & Scruggs and Sam Bush.

This is more than merely cool. It’s important. Immediately outside IBMA’s confines, as all this was going on, in real time, President Trump was fanning flames of anger over peaceful, protected protest of police brutality. Issues of LGBTQ+ inclusion regularly produce cascades of vitriol and culture war, where all that was hoped for was the same thing artists hope for on stage — listening — and maybe some empathy and vulnerability for good measure.

Shout & Shine takes its name from a Christian hymn written in the 1950s that’s been covered by gospel groups and bluegrass bands. The first verse is heavy-handed with its promise of being issued a robe and crown upon entry into paradise. But the second and final verse has a nicer prophesy for the musically minded:

I’ll never be lonesome in that city so fair

And all will be so divine.

Many of my loved ones and neighbors will be there.

In heaven, we’ll shout and shine.

We want people to sing about being lonesome in bluegrass. But actually being lonesome? Not so much.

Photo credit: Willa Stein. Lede image: The Ebony Hillbillies headline Shout & Shine.

Craig Havighurst is music news director and host of The String at WMOT Roots Radio in Nashville. Follow him on Twitter @chavighurst