The Lonely Heartstring Band curiously placed “The Way It All Began” in the middle of their new album, Smoke & Ashes, yet it serves as a cornerstone of the project. Somewhere between sweet romance and saying goodbye, the song conveys a contrast of emotions that are woven throughout the album. They recorded the album with Lake Street Dive’s Bridget Kearney as producer; together they ventured beyond bluegrass boundaries while retaining the acoustic approach that led to an IBMA Momentum Award in 2015, as well as a deal with Rounder Records.

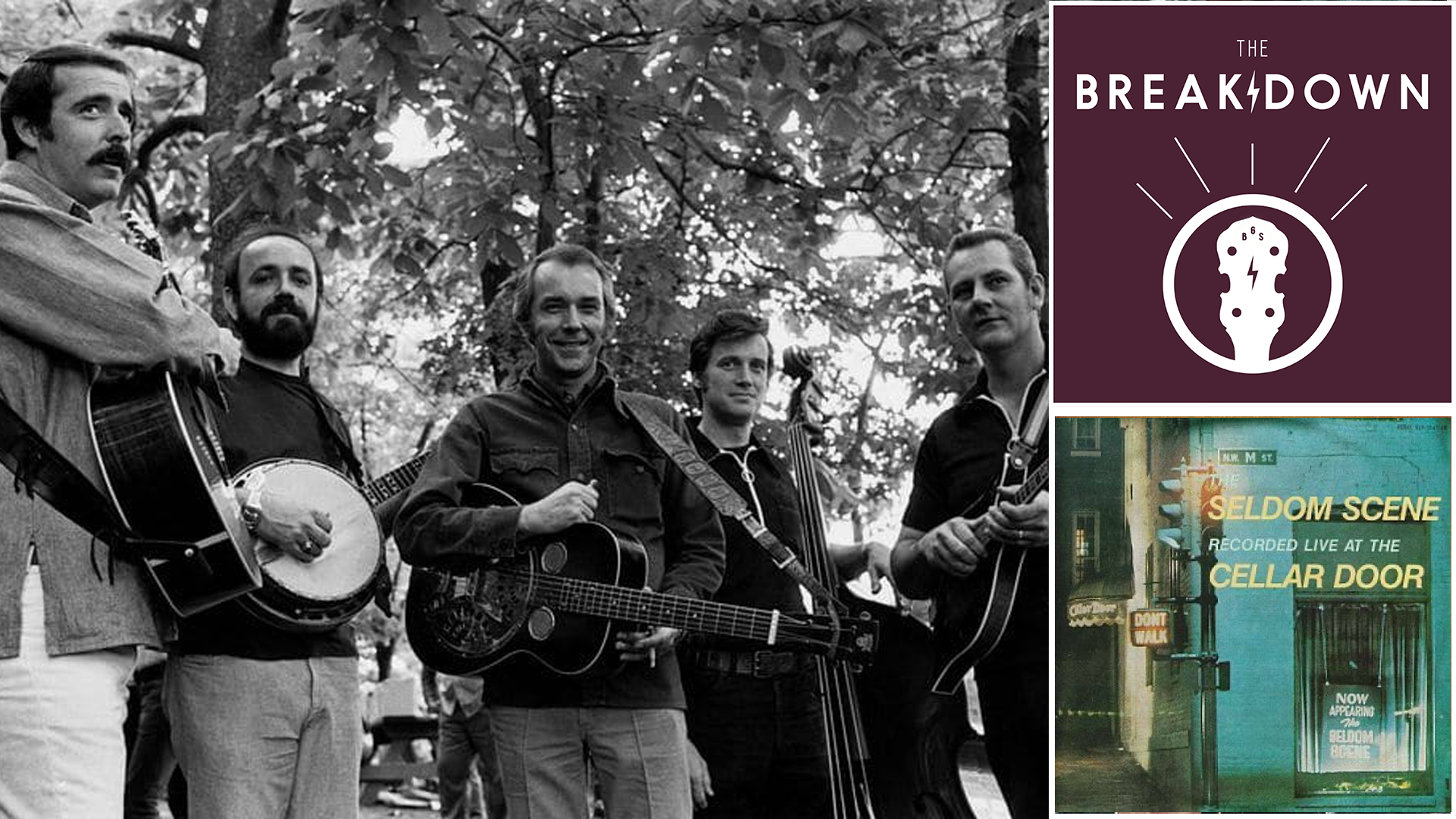

The band is composed of twins Charles Clements (bass) and George Clements (guitar), Gabe Hirshfeld (banjo), Patrick M’Gonigle (fiddle), and Maddie Witler (mandolin). Starting a winter morning in Boston with mugs of hot tea, the Clements brothers fielded a phone call with the Bluegrass Situation.

BGS: Let’s start with “The Way It All Began,” which has a wistful and sweet quality. What were you hoping to evoke in that song?

George: Patrick brought that song to the band, and he told me it was his idea about how a relationship starts. It’s two people who are young and traveling together, trying to capture that reflective, looking-back element.

Charles: I’m pretty sure it’s based on a true story from his life and I think it’s actually bittersweet. It’s a moment that comes together in a relationship, for a summer, then by the end, there’s distance. It’s the way it all began, but the way it ended too.

George: We had a lot of fun arranging that song, coming up with different ideas, like little modulations in the middle with the fiddle.

Did you have a certain sound in mind when you went into these sessions?

George: Yeah, I think we wanted to capture the natural sounds of the instruments as best we could. We recorded this record at Guilford Sound in Vermont and that studio has a really cool, natural reverb chamber, so we were able to capture some spaciousness in that.

Charles: For that song, a high priority was to make sure it had that laid-back, California, spacious, unhurried feeling. We went back and forth on tempos quite a bit actually – that’s too slow, that’s too fast. It’s a delicate thing because you want things to groove and move forward, but you don’t want to lose the character of the song just because you want more energy. A great example of that is Neil Young. He’d do these slow grooves that still keep you rolling forward, but they’re not fast songs.

The song “Smoke & Ashes” has some interesting imagery in there. Several times, you are singing “Come back…” Who are you saying that to?

George: When Patrick and I were coming up to the lyrics to that, it was like a post-apocalyptic song in the sense that we’re losing a lot of things that we love in life. They’re slipping away, like maybe nature is becoming threatened by mankind. I think the “come back” is like, let’s return to the things that matter most. Come back to your senses, come back to reality. Come back to the moon, the sun, the things that are universal.

Why did that song make sense as the title track?

Charles: That’s a good question. We went back and forth on album titles. We settled on it because we think it has good imagery and openness to it. Smoke and ashes can be a pessimistic thing, like things have burned down, but it’s also kind of optimistic. It has a sense of rebirth to it. There’s a sense of ending and starting.

George: We thought it had enough space for the listener to put their own interpretation to it. And I think that “Smoke & Ashes” is a pretty unique track on the album because it’s real slow and spacy, with lots of interesting chord changes. I think we all liked the way that track turned out.

“Just a Dream” has a cinematic, sweeping quality to it. Are you all inspired by movies or film scores when you write music?

Charles: Yeah, when I wrote that song, I think I was letting my imagination run free and create these kind of dreamlike images. … You know, an album is like the inverse of a movie score. The listener obviously has to bring their own imagination. [An album] requires a lot more of an audience than a movie does. Movies sometimes are just gonna give, give, give. With a song you have to bring a little more attention to your own life, your own imagination, and fill it in more with questions about, “What are they trying to say?” I think about that a lot. With songs, you have to supply your own movie a little bit.

Do you all collect vinyl?

George: Charles is a big collector. Patrick has a lot. I don’t have a vinyl collection at the moment because I don’t have a record player. [Laughs] I’ve been moving around so much that I just don’t want to lug all of that around – but someday I’d like to have a collection.

Charles: Maddie, our mandolin player, has probably the largest collection in the band.

Do you turn each other onto music that you discover on your own?

George: Oh yeah. We spend so much time in the van. That’s all we do in the van, either listen to audiobooks and podcasts, or just show each other new music. We’ve got a big text thread going where things will get sent out sometimes.

Charles: Yeah, the Lonely Heartstring Band text thread goes back about five or six years now. It’s full of stuff! (laughs)

George: Somebody should transcribe that. It would be a great, hilarious coffee table book.

I like to hear you all sing together on “Only Fallen Down.” So I wanted to ask, who are some of the vocal groups that you really enjoy?

George: Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young comes to mind. We also really like The Wailin’ Jennys. Charles and I grew up with a lot of Everly Brothers and Simon & Garfunkel, though that’s more two-part harmony.

Charles: The Trio album – Emmylou Harris, Dolly Parton, and Linda Ronstadt. That’s powerful three-part harmony there. And obviously the Bluegrass Album Band, as a model of how to do tight, three-part, bluegrass harmony.

That song seems to be about a temporary setback, but with a sense of determination to go on. Do you see some parallels in your own life? That decision to forge ahead through the challenges?

George: Yeah, like every day. [Laughs] Being in a band is not easy. There are always challenges in relationships. So I think the lyrics reflect an intimate relationship between two people but it can have a universal appeal. Any time you have a challenge or you feel like you’re ready to give up, you can always change your attitude and say, “Well, yeah, this is a setback. I can pull myself up by my bootstraps and keep on going.”

In that song, there’s a line that says something like “Reach out for a hand to pull me through.” That’s a line that we came up after the song was written. That line replaced another one lyric. I really like that line because I think the hardest thing to do when you’re down is to ask for help. Sometimes we wallow in our own misery, and I think what you have to do is ask for help. You don’t have to do it on your own, basically. If you’re having a tough time in life, there are always people who want to help. That’s the amazing thing about the human spirit. We are here to help each other.

Charles: “Only Fallen Down” is a simple song when you think about it. It has a clear, straightforward message. I think that song stands out on the album because it is like a Beatles-esque sweet song. It’s very direct, not trying to be obtuse or metaphoric. I think we were ready for something like that, where you can feel good, like a simple soul song where we’re not trying to say anything other than that simple idea.

Do you think your audience will hear a departure from your prior album when they hear this one?

George: Yeah, I think they will. When I listen to our first record, it’s a little more traditional style – although not super traditional. We still had our own take on things. But this record doesn’t have any covers. It’s all our own original music. I think it reflects more of our unique musical sensibilities without trying to be anything other than what we are. We’re not using electric instruments, we’re not using drums. We still have that Lonely Heartstring Band sound.

Photo credit (on location): Louise Bichan

Photo credit (studio): Mike Spencer