In her dynamic, restless career, Becca Stevens plans to never repeat herself, like the proverbial waterway that’s never the same river twice.

Since being noticed by New York Times jazz critic Nate Chinen in 2008 as a 24-year-old “best kept secret,” she’s collaborated with: David Crosby and his Lighthouse Band; jazz orchestra Snarky Puppy; the modernist ensemble Kneebody; pianist Brad Mehldau; harmony genius Jacob Collier; the neo-classical Attacca Quartet; and others. Her five solo studio albums, especially the mind-stretching and richly grooving Regina (2018) and Wonderbloom (2022), have mingled folk-grounded melodies and jazz-deep harmonies with pop dazzle. The common denominator has been her uncommon voice, which is conservatory-trained, but utterly unique and enthralling. She is, in my humble opinion, one of the finest overall musicians making song-based music today, a peer to 21st century savants St. Vincent and Madison Cunningham.

One frontier that remained for Stevens was, ironically, the most obvious for a singer-songwriter – the solo acoustic album. Her version of this venerable format finally arrived in late August with Maple to Paper, a 13-song collection that was shaped at every level by a series of landmark life events. After marrying Nathan Schram, violist in the Attacca Quartet, she gave birth to daughters in 2022 and 2024. Their family moved from New York to Princeton, New Jersey. Her mother died, as did her close collaborator and friend David Crosby.

Stevens alchemizes this season of change, love, and loss through songs that challenge conventional forms with rich and fearless lyrics that play at times like Emily Dickinson set to classical guitar. On the cover, she’s demurely naked behind a guitar. In the grooves, she’s as vulnerable as we’ve ever heard her. As she told me of her emotional multiverse of the past few years, “I felt uncomfortable about sharing it, but I also was like, well, if I’m going to do this, I might as well make it completely exposed.”

It’s easy to suppose that the changes of the past few years – moving, having children, losing your mom – made a solo acoustic record sound more appealing at both artistic and practical levels?

Becca Stevens: Absolutely, yeah. You’re spot on. Two things can be true. So the choice to do this album completely solo and from home both served the concept and integrity of the album. But it also was maybe the only way that I could have gotten it done during that time.

Just to put that into perspective, you know, there was the logistics of the grieving. The loss of my mom was super fresh, and I had a six-month-old who was part-time in daycare. And then towards the end of the recording and writing process, I was pregnant again. So there was the logistics of being a new mom, of having morning sickness, of being in a new place, of grieving my mom, and all of that was so much more possible to do from home. But I resisted it.

For a long time, I had the idea of recording the demos at home and then going into the studio. But I went back and forth a lot with Nic Hard, who mixed it with me. He also did Wonderbloom. And the deeper that we got into the material, the more crystal clear it was that the songs were best served if performed live – guitar and singing at the same time – and performed at home, where I was really in the character and in the feelings.

Did writing and making art feel like what you wanted to do under all those cross-cutting pressures and changes, or did you have to force yourself a bit through the work?

“Want” is maybe the wrong word. I felt like, at least for the grieving part, I had to do it because it was like I was going to explode if I didn’t do something. And it was a confusing loss – something that left me with a lot of questions. Ever since I was a kid, I’ve been somebody who processes confusing emotions through writing songs or stories, or art in some way.

I felt like I needed to do it. But also, yes, there were times where I just absolutely did not want to and just wanted to lie on the floor. And I had to find a way to incorporate that as part of the process, so that I could forgive myself. I literally had a futon on the floor of my workspace, where I told that part of my brain, “You are invited to lay down there whenever you need to. You’re not at a studio. The clock’s not ticking. You’re not paying for this.” I called it my Womb Room. And I would put on salt lamps and put the lights down really low and lay down. And then some of the songs came from that space.

Some of these feel more like classical art songs than folk songs, in that they’re not shaped around a set number of measures or predictable beats. Did they feel a bit like that to you?

Yeah, the song “Payin’ to be Apart” comes to mind. It definitely felt that way; a little less folky, more like poetry that just happens to be on a wave of music. It’s interesting to hear you say that, because in the writing process – harmonically and in the accompaniment – I took a much simpler approach than what I have done before, on Regina or Wonderbloom, on everything really. Because I put so much intention and honesty and, like, blood, sweat, and tears into the lyric, I gave myself permission to let the waters that it was floating on be a little less turbulent artistically, a little less complex and a little more like I was trying to cradle them and deliver them in a way that takes care of them and makes it easier to metabolize – or something.

Was your mindset different, knowing there’s not going to be the grid of the drum beat? Can drums be a bit of a cage sometimes?

Yeah, they can be a cage. But they can also be like something that’s really cozy to lean on in the arrangement. Like, I can drop everything and have it just be drums and vocals for a verse and it feels really good. But for this album, I set a goal that the songs are meant to be performed as just me and the guitar, because that’s how they were recorded. That means that whatever break that I gave you in Wonderbloom by stripping down the arrangement and going to drums now needs to be created with whatever tools I have by myself, whether that’s narrative, or a right hand finger pattern, or fill in the blank.

This made me wonder how much you have performed solo acoustically in your career, given the emphasis on arrangement on a lot of your records.

Quite a bit, yeah. I have a lot of respect for my bandmates. And if there were ever gigs that we were offered where I felt like I couldn’t cover their fee and treat them well, I would just take it solo. I’ve done that a lot. I’ve done a lot of solo tours. A lot of my writing has started out solo, and I have solo versions – for example, “You Didn’t Know,” the song from Wonderbloom that was inspired from watching the documentary about R. Kelly. That song, I poured my heart out solo and then stripped the solo version back when I was in the studio turning it into the Wonderbloom version.

Solo feels like a home base to me, and it’s something that I think I’ve resisted, because maybe I felt like it wouldn’t be enough. There’s this narrative, especially in the booking world, that they don’t want to book you unless you have more than one or two people on stage, because it’s not enough to create the energy to get the focus of the audience. And maybe it’s not loud enough, you know? I also had that in mind. This might not be very marketable, but I’ve got to do my best to just serve these songs to the best of my ability. And it’s got to get done anyway, because this is how I’m processing this part of my life,

Meanwhile, your tempo of collaborative work never seems to let up. I have my personal favorites, but can you address some of your favorite partnerships here in the last few years?

We haven’t mentioned this yet as part of the story of this record, but knee-deep in the writing and recording stages of this album, we also lost David Crosby. I’d already gotten punched in the face and then I was like, kicked on the ground. Not that it’s about me. The whole world grieved that loss. As I mentioned, when I lost my mom, it was a very complicated grieving process. I took a lot of inspiration from listening to albums like Sufjan Stevens’s Carrie & Lowell, where it’s okay for grief to be ugly and complicated and to show that. But with Croz, it was so sad, because I loved him so much, and I loved being in his band, and I loved writing music with him. But the presence that he held in my life didn’t diminish. I couldn’t hug him, but there was this sort of heavenly presence when I was writing the songs for this album, where I could hear him and see him in my mind, kind of rooting me along.

And tell me about Michael League of Snarky Puppy and the universe that he inhabits with the GroundUP record label, which has been supportive of you all this time. It’s such a fascinating record company. I feel like they’ve got a lot to teach the music industry about curation and cultivation of a tribe, and I’d love for you to remark on how that model has served you.

I like the word tribe. I often think of it as family, but I think tribe is even stronger. I feel safe with that label in a way that I’ve never felt safe with labels before, especially major ones, where, if you’re not performing exactly the way that they want you to, you get kind of put on a shelf, and then your art doesn’t get heard because, because you’re not pleasing the corporation.

With GroundUP, I’ve always felt like whatever I’m getting into is what they want me to do. They’re like, “Your health and happiness and artistry come first and if that’s what you need to make right now, we’re behind it.” And I can’t tell you how liberating and comforting that is as an artist to know that the people that are helping you put your music out have your back. And we all love each other too. We all play together and love each other too.

And speaking of Sufjan Stevens, you got to be on Broadway in his Illinoise musical. What did that add to your world?

Yeah, it was a limited run on Broadway and I did half of the run. So I had Isla, my second daughter, on February 24 of this year. And then I got a call from Timo Andres, who did the orchestrations, saying, “I know you’re on maternity leave. This is crazy. I shouldn’t even be calling you, but I can’t not think of you for this role. Is there a world where you would ever audition for this?” I was like, “Yeah, I could audition and see what happens…” and didn’t expect to get it. I came in with my newborn baby. I handed her to my manager, did the audition, and they called me within a day and said they’d love for me to do it.

Initially I thought, “There’s no way.” I’m giving you all of this extra detail because a huge part of the experience for me was the chaos and the balance of the life that I was living at home for the first half of that day in Princeton – nursing my baby and being a new mama – and then handing her to my husband and jumping on the train for two hours, going into the city just in time to perform, and then coming back home and doing it all again and nursing through the night. It was this superhuman thing that initially I thought, “Oh, there’s no way this is going to work.”

The whole experience was like a dream state – being on stage and singing that music, which I’ve loved for so long. And also, having it not be about me was very refreshing. I’m not the band leader and I’m singing someone else’s music as a narrative that’s coming from the bodies of the dancers. We can lean on the coziness of the production, and just enjoy it.

I would say coming out of that helped me to be less self-absorbed. The headspace that I was in for Maple to Paper was very me, me, me, me, me, me. And then Illinoise was like, “No, it’s not about you. It’s about being in service to something greater than you.” Whether you’re writing a song about your feelings or singing somebody else’s, that’s always what it’s been.

Editor’s Note: Need more Becca Stevens? Check out our recent Basic Folk conversation with Stevens here.

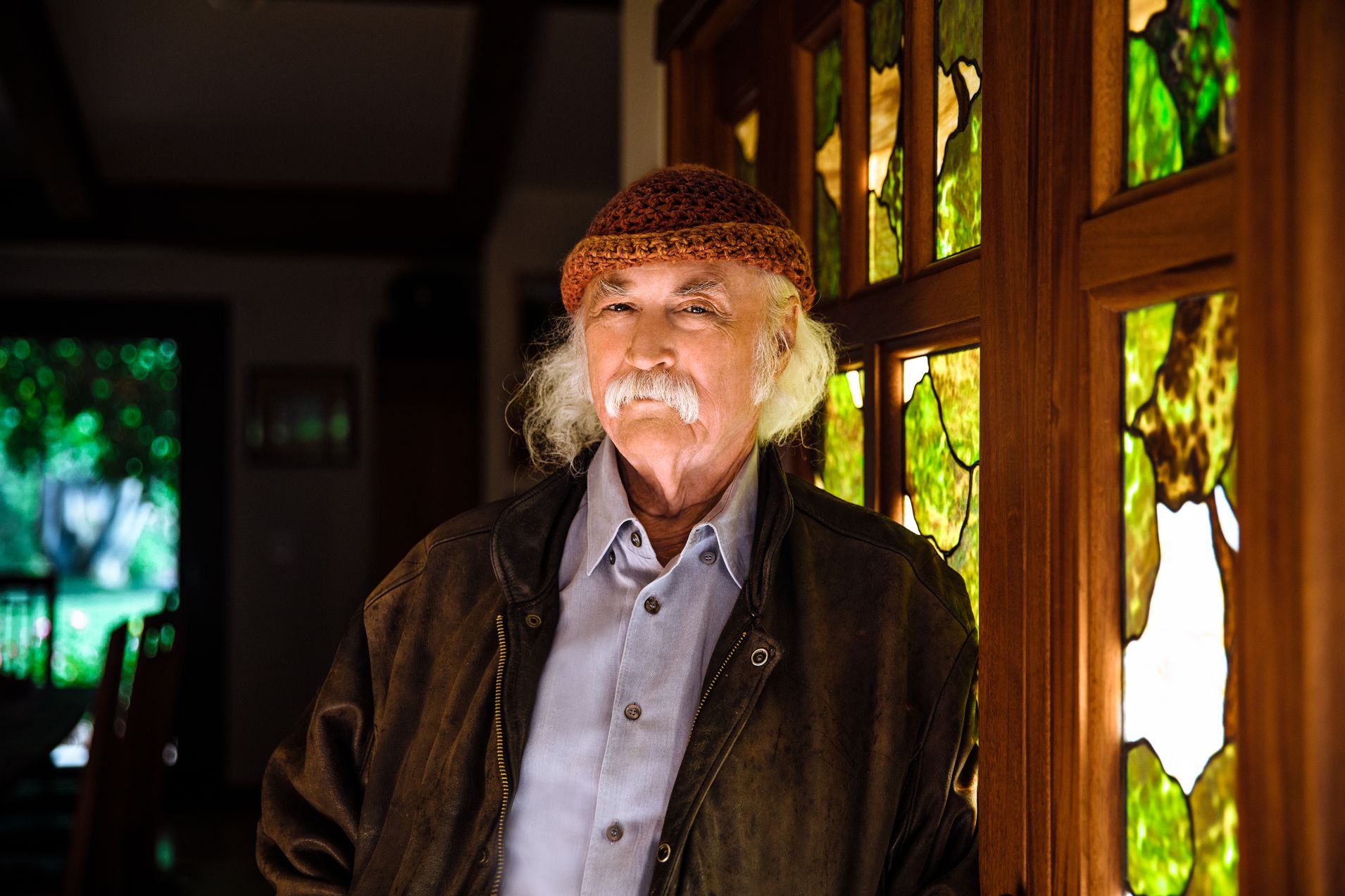

Photo Credit: Shervin Lainez