Bloodshot Records’ 25th anniversary party is taking place in Chicago this Saturday, and they’re gonna party like it’s… 1994.

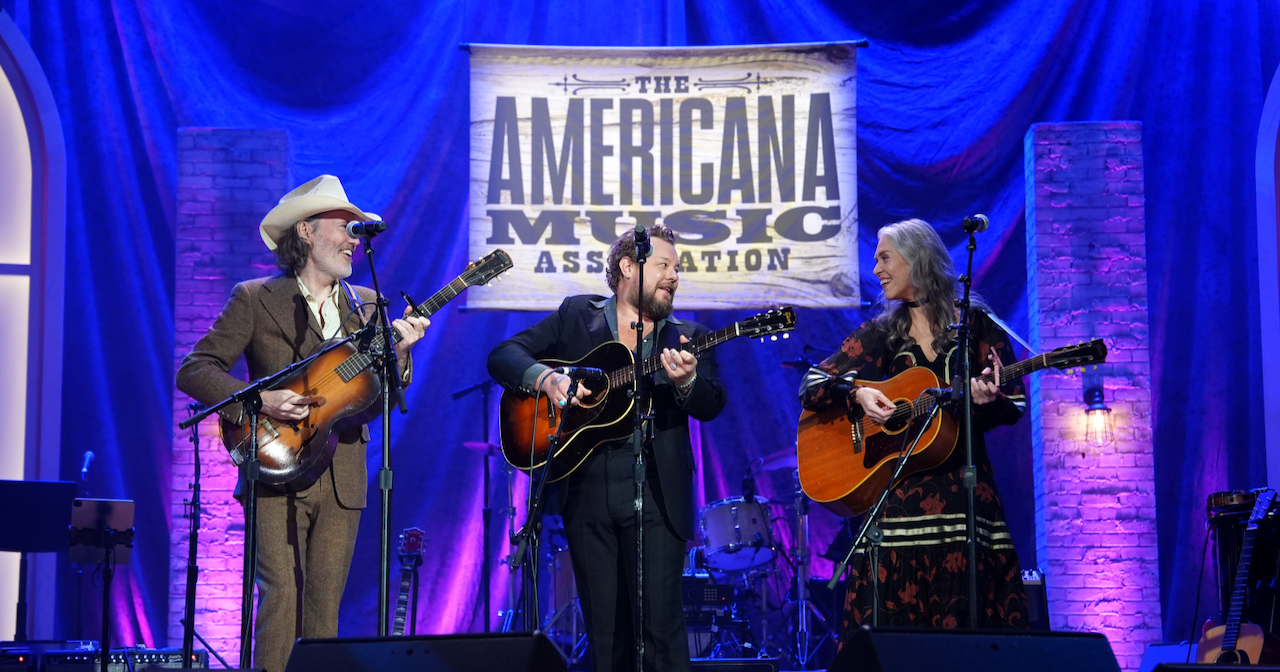

Long before the term Americana was coined, this fledgling Chicago label was issuing records by Robbie Fulks, Old 97s, and other road-worn musicians who built their careers on a mix of country and punk that the label initially termed “insurgent country.” That description didn’t last but the label forged on, with compelling artists and songwriters like Jason Hawk Harris, Sarah Shook & the Disarmers, and Luke Winslow-King now on the roster.

Bloodshot Records co-founder Rob Miller fielded some BGS questions by email. Check out the newest release, Too Late to Pray: Defiant Chicago Roots, at the end of the interview.

BGS: Launching a record label is a pretty big risk, then and now. Was there a specific moment that convinced you, “OK, the time is right to do this”?

RM: Au contraire! Risk never, ever crossed my mind. When you don’t have a business plan, an expectation of success — let alone longevity — or any idea what you are getting yourself into, ignorance and naiveté are powerfully liberating. The whole idea was, at the very least, a release from the drudgery of drywalling shitty condos in Wrigleyville and Old Town.

The three original partners ponied up a couple of grand from our day jobs, put together our first release, For a Life of Sin, and the day the CDs came back from the manufacturer, POOF!, we were a “label.”

I can’t imagine doing something as ridiculous as that now.

What do you remember about those first few conversations with your friends and your peers when you shared your plans to launch Bloodshot?

Practically nothing. It was a very blurry time. It was at a time in all our lives when all was action and creating and the moment without much thought to consequences. We were just so excited at the prospect of shining a light on this weird little scene in Chicago that I doubt anyone could have talked me out of doing it. The real world had not yet muscled itself to the table and I’ve managed, in many ways, to keep it at bay all these years. Oh, and then there was the tequila. As I said, very blurry.

Why did the phrase “insurgent country” fit the Bloodshot Records vibe, do you think?

It’s something Eric Babcock (one of the original founders) and I came up with one day drinking beer in my backyard — never let two English majors get drunk when there’s a thesaurus within reach, by the way.

We were looking for a catchy way to describe what we were doing, something that spoke to the outsider aspect and added an edge to the frequently off-putting “C” word. At the time, there wasn’t much critical language or reference points surrounding the melding of roots and punk. So, before someone else hung a dreadful tag on us like cowpunk or y’alternative, we thought it would be wise to TELL them what to call us.

Print media was so prevalent as this label was getting off the ground. What role did music journalists play in making Bloodshot a success?

Wait, we’re a success? Who knew? Where’s my pony, dammit!

Having spent my formative years reading fanzines and indie publications, persuading glossy mags or acclaimed daily newspapers to pay any sort of attention to us never crossed my mind. We did then, as we do now, focus on the grassroots. We work from the bottom up, rather than wait around for some “tastemaker” to tell the world it’s OK to like us or our artists. It was in those locally-based outlets where people could write about us with passion and without concern for circulation or broad appeal.

However, there are times when our tastes and popular culture intersected (Neko Case, Justin Townes Earle, Ryan Adams, Old 97s, Lydia Loveless, among others) and the wider world and folks higher up the media food chain paid attention to us. Usually that would take the form of a “trend” piece along the lines of “the new sound of country” or “Whiskey-soaked barn-burning punks” or some such shit. They’d be reactive and reductive, but tried to sound bold and cutting-edge by calling out some hot, fresh underground movement.

And that’s all great, but it doesn’t influence what we like or how we go about what we do.

Don’t get me wrong, or think me the King of Cynics (I am merely a prince), there were some insightful and humbling pieces in places like Rolling Stone, GQ, Village Voice, New York Times and the like. In NYC 1996, we had an afternoon barbeque on the Lower East Side with the Old 97s, Waco Brothers, and others. It was during CMJ and since they wouldn’t let our bands into the festival, we put on our own party (a precursor to our longstanding shindig at the Yard Dog Gallery during SXSW). I went outside to check on the line that snaked down the block and saw a couple writers from Rolling Stone and the legendary Greil Marcus trying to get in. Yikes. Things like that helped lend an air of legitimacy to our strange little crusade.

Who were some of the earliest champions for the label?

Fans, largely. Weirdos like ourselves who quickly responded to what we were trying to do. People who were fed up with the co-opting of the underground, of Lollapalooza, of Martha Stewart “grunge-themed” parties; people who were looking to classic country for the freshness, excitement, and freedom that they used to find in punk; people who were discovering that Johnny Cash, Loretta Lynn, and Hank Williams were 1000 times more interesting and relevant than the Stone Temple Pilots or the Red Hot Chili Peppers would ever be; people who were starting up, or involved in already, their own scenes in their cities who saw us as willing collaborators.

Fortunately, many of these collaborators also worked in the biz, as writers, DJs, promoters, record store owners, distributors, and club owners. We were able, in pretty short order, to stitch together an ecosystem of people who genuinely dug what we were trying to do and could help spread the word to the benefit of all. It was very much a community spread out across the country.

How has the Chicago music scene factored into the Bloodshot Records story?

There isn’t so much a Chicago music “scene,” as there is a Chicago “hustle.”

When I moved to Chicago, I was floored by the vast array of music available to me on any given night. So many clubs, so many bands, so many neighborhoods, so many options. Given our position in the middle of the country, most touring bands stopped here. Rent was cheap. Labels arose in a non-competitive environment which fostered a vibrant, organic and sustained creative burst. Since Chicago is a working town, rather than a company town like NYC, LA, or Nashville, there was an incredible amount of freedom to create and perform without fear of upsetting the “industry” or making a jackass of yourself and failing during your “shot” in front of A&R goons from a major label.

Do what you do. Try new things. We didn’t break rules so much as we never knew what the rules were in first place. Club owners took chances on our bands early on and became fans and advocates, the media cared and wrote about what was happening at the street level, and there were plenty of record stores and left of the dial radio lending encouragement. Coming from a place that lacked such a supportive infrastructure, I never, ever take it for granted.

I firmly believe that Bloodshot would not have thrived anywhere else.

At the time the label launched, vinyl pressings of new releases were very rare. How did the label respond when you all realized that vinyl was making a comeback?

Very true. Early on, other than a series of 7” singles, we didn’t do any vinyl. Occasionally, a European company would license a title and press up 500 LPs or so, but otherwise, it was a dead format. That pained the record nerd buried deep in my DNA.

So, we were quite happy to help with the resurgence of LPs. At first, we’d tentatively press up 500 or 1000 of only the releases we expected to do quite well; LPs are expensive, time-consuming and temperamental to manufacture, and unsold LPs take up a lot of space in our tiny warehouse. AND no one was sure if this was a quick blip or a passing fancy, so all the extant pressing plants were log-jammed for months at a time. But now, with new pressing plants finally opening up, virtually every release has a vinyl component to it and we’ve re-released music never before available in that format as well.

I think people who, by and large, grew up with downloads and streaming respond to vinyl because of its tactile and totemic connection to the music and the artist. As the saying goes, you can’t put your arms around an MP3. It makes the LP a very durable and loveable format.

What do you remember about Bloodshot’s first website?

Funny, I was just talking to an IT person about this the other day. When we moved into our current office 20 years ago, we had one modem for the entire office. If someone needed to get online, they would run through the office telling people to get off the phones so they could log on. We wrote letters and used faxes. We even called people on the corded telephones and talked to them — how very quaint.

If we wanted to edit our site, we’d have to compile a list of changes, and fax them over to our “programmer.” We did that usually every two weeks or so. From where we sit now, it feels so distantly and hilariously primitive, like I was the chimp smashing bones with a femur when the obelisk appears in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

Every once in a while, someone will say something like “I googled that DSP” or “the Wi-Fi crashed and I can’t download the WAV files” and think, good Lord, what would such utterances have sounded like back then? They would have locked you up or tossed you off the bus for being a loony.

In this era, having a record label isn’t essential to release music. However, from your perspective, what are some of the benefits of having label support?

Several years back, the conversation did turn rather aggressively towards “why even bother having a label?” True, the monolithic aspect of THE LABEL has been wholly and, in many cases, rightfully demolished by the internet.

However, artists are artists. They should create and perform. They should not be burdened with the time-sucking (yet necessary) banalities of promotion and business.

That’s where a “team” like us comes in — perhaps that’s a more relevant term than “label.” We can take all those nagging organizational bits off their plate and build the brand. We keep the trains running on time (I refer, of course, to European and Japanese trains, not Amtrak). And, let’s face it, many possessing the — how shall we say? — artistic temperament do not also possess the logistical grace to tackle all the infuriating minutiae that make the whole machine run. No one asks me to write a catchy melody or craft meaningful lyrics delving into the human condition. No one should ask the artist to make sure the digital service providers are given the proper metadata or set up an in-store performance in Fort Collins Colorado.

What excites you the most about the next 25 years?

Ivanka 2040?

The death of the Death of Irony?

Jet packs?

(Hopefully) outliving Henry Kissinger.

Florida and Mar-A-Lago sinking into the sea once and for all?

Making sure the soundboard at the old folks home is powerful enough for Jon Langford’s shouting to be heard over the Matlock re-runs?